You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStockphoto.com/William_Potter

State funding for higher education remains below pre-recession levels and will likely stay that way, a new report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers association shows.

The fiscal 2019 State Higher Education Finance report was well underway before the coronavirus pandemic tore through higher education budgets. But Sophia Laderman, senior policy analyst at SHEEO and lead author of the report, considers it a useful tool as higher education braces for a recession.

“Think of this year’s report as the next baseline for the recession we’re coming into. Public funding for higher education has never been so low going into a recession,” Laderman said.

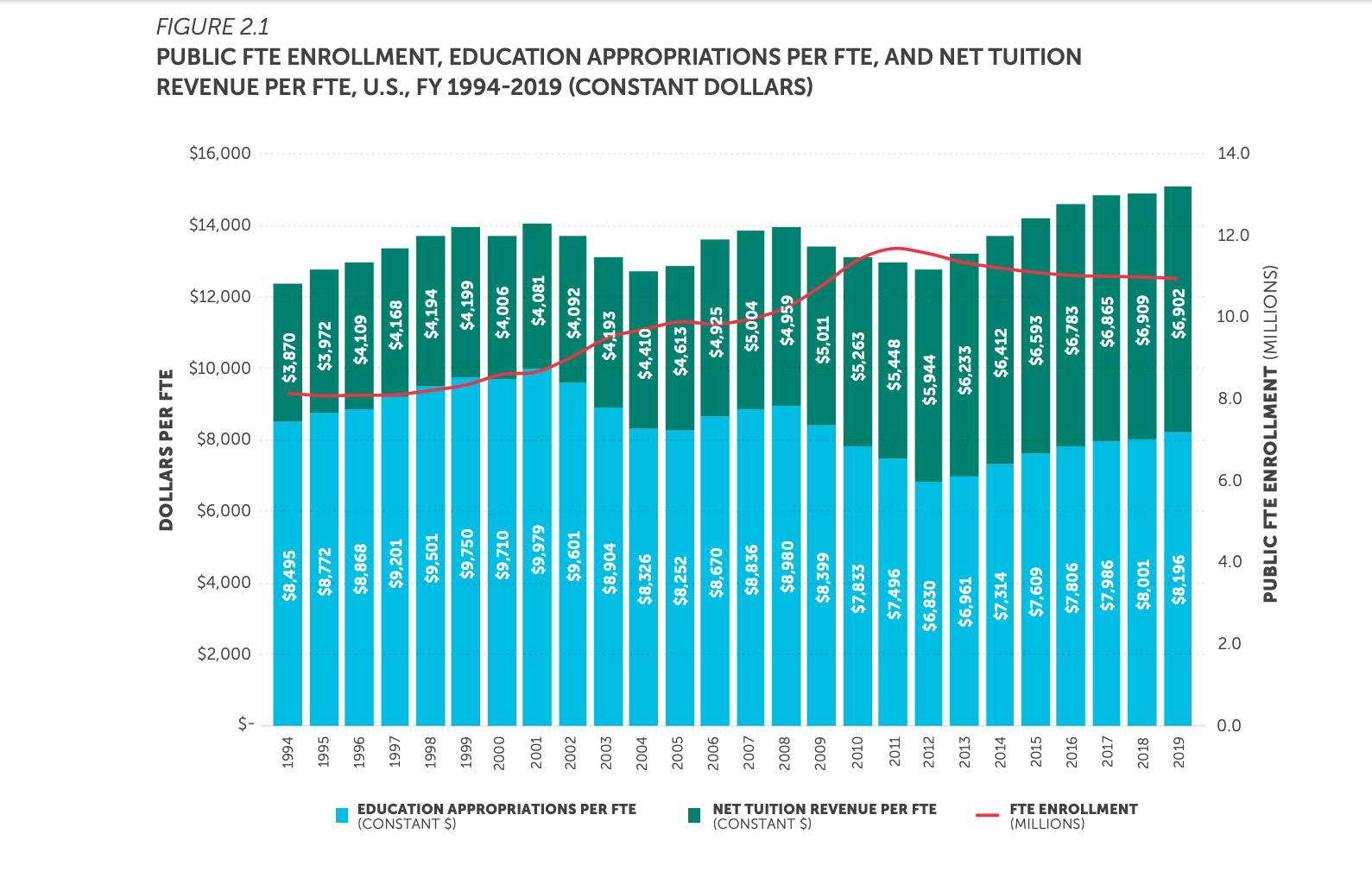

State funding nationwide is nearly 9 percent below pre-Great Recession levels and 18 percent below where it was before the 2001 tech bust. Per-student education appropriations increased 2.4 percent between fiscal 2018 and fiscal 2019, but 2019 marks the “likely end” to post-recession recovery funding, the report states.

“With every recession, funding for higher ed has had steeper declines and shallower recoveries,” Laderman said. “So we’re coming up to this next one at a worse spot than ever before.”

As public funding declines, institutions increasingly rely on revenue from tuition and fees. Net tuition revenue held steady at $6,902 per full-time-equivalent student, compared with $6,909 in fiscal 2018 and $5,011 in 2009, the report shows, adjusting for inflation. States appropriated $8,196 per full-time-equivalent student, compared with $8,001 in 2018 and $8,399 in 2009.

Combined, education appropriations and net tuition revenue fund $15,098 per full-time-equivalent student, an all-time high. Two-year and four-year public higher education institutions serve a total of 10.9 million full-time students nationwide.

Historically, institutions facing state budget cuts can fall back on tuition and fees to carry them through a recession, but experts are uncertain whether that precedent will apply to an upcoming, coronavirus-caused economic downturn.

"If their funding is cut on both sides, and there’s costs related to technology and going online and all those kinds of things, it’s really tough to say what will happen," Laderman said. "It’s pretty much a given that state funding will decline, so the enrollment and tuition revenue questions are all that’s unknown at this point."

Kevin McClure, associate professor of higher education at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington, noted that regional and community colleges will be most impacted by cuts in either direction.

"Some of the regional public colleges and universities, they tend to be the ones that rely most heavily on state appropriations and on tuition revenue. They have the combination of being hit the hardest in the event that there are state budget cuts but also [being] hit really hard in the event that there’s a decrease in enrollment," he said.

It's too soon to tell whether enrollment will be an issue long term.

"If it’s the case that we see an uptick in enrollment, my guess is that we’re probably not going to see it in summer and we’re not going to see it in the fall," McClure said.

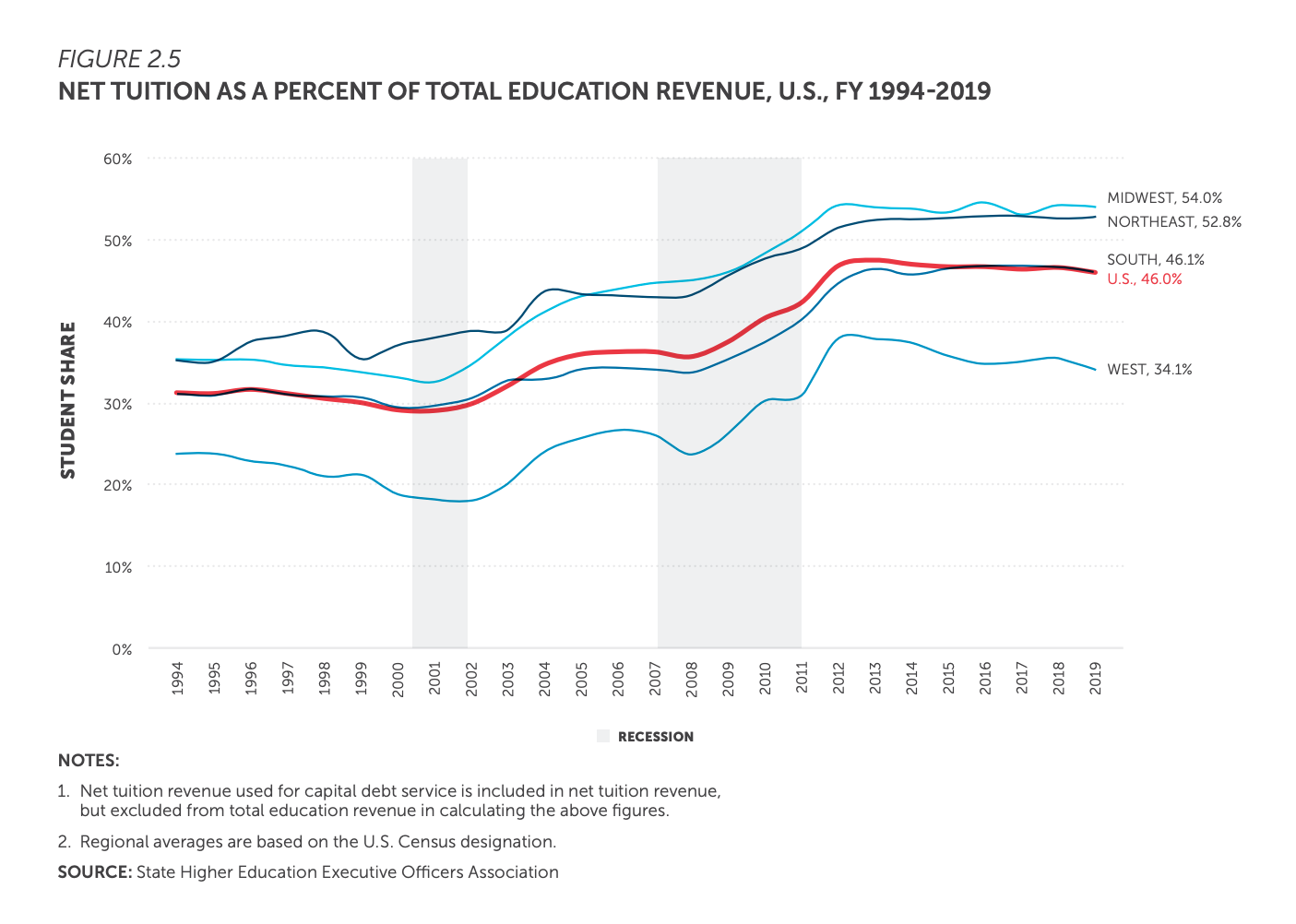

Student share -- the percentage of all higher ed revenues coming from student tuition dollars -- is continuing to rise across the country. Typically, student share rises during recessions and levels off during recovery periods, the report notes. In the next recession, national student share is on track to pass 50 percent.

This is noteworthy “because it provides a sense of who is the largest shareholder in public higher education,” McClure said. “It’s pretty clear that it’s no longer states.”

The report highlights many national per-student metrics, which are skewed by the largest states, Laderman said. Those states often provide more public funding per student, driving down national averages for student share. Though the national average falls short, more than half of states have already surpassed 50 percent student share.

"Obviously, the largest enrollment is in California. So California, with their very low tuition, really pulls the U.S. average down and makes things look a little less privatized than they really are," Laderman said.

Brian Prescott, vice president of the National Center for Higher Education Management, a private nonprofit firm that consults with colleges and universities, said what some see as a long-term trend toward the privatization of public higher education is contributor to declines in state funding.

“Higher education, like lots of things, has become viewed as a private good more so than a public good,” Prescott said. “As a private good, folks generally think, 'You’re taking advantage of it, you ought to pay into it more.' So the logic there is increasingly, ‘If I’m going to get a benefit from it personally, then I should have a stake in it.’ The public benefit arguments, which I think are pretty compelling, aren’t as compelling in the statehouse.”