You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

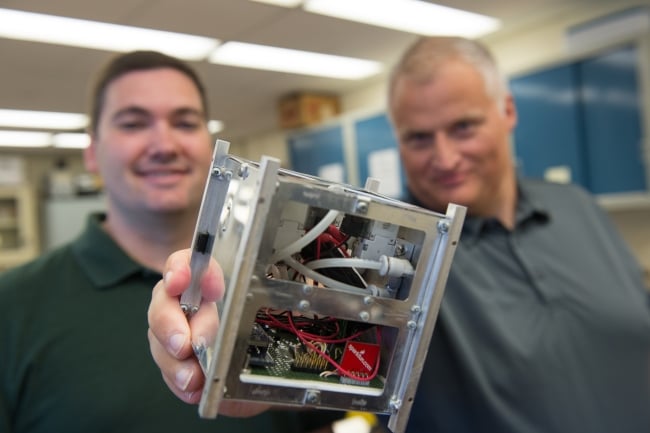

Ryan McDevitt and Darren Hitt won awards for the propulsion systems they developed for small satellites.

Sally McCay

For decades, professors whose research held promise for practical applications had to search largely on their own for investors. But a growing number of efforts are bringing to academe the same kinds of opportunities once available only to young app developers and business school graduates.

Perhaps most notably, SPARK, a project that began at Stanford University's medical school in 2006, has spread to more than a dozen universities worldwide, including the University of Vermont, where since 2013 it has handed out grants of $50,000 to small companies based on professors' research to help them attract investors.

Dryver Huston, a longtime UVM engineering professor, helped create a group at UVM and the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga that proposed a way to collect better data on ground-penetrating radar, doing it more quickly but with fewer radio waves. The Federal Communications Commission, which regulates the practice, has raised alarms that traditional methods can interfere with air traffic control systems.

Huston is sitting out the competition this year, but in years past he said he “got some good feedback” as well as funding that helped leverage further investments, primarily from the federal government.

At the final round of pitches at this year's competition, held late last month, a few panelists offered similar comments, telling one duo -- a husband-wife UVM team developing a biofeedback smartphone app for panic attacks -- that they were entering an “extremely crowded” field, dominated by heart rate monitoring devices like the Apple Watch, with big, sophisticated software and hardware developers behind it.

Another panelist said flatly, “I’m going to be very frank: I hate the idea.” One problem, he said, is that a prospective user might not be able to find his or her phone -- or might experience a panic attack in the woods, out of range of cellphone connectivity.

The company hopes to market the app, tentatively named [wepanic], to 100 universities in the first two years, saying the proposed $20,000 annual subscription rate represents “a fraction of the cost of hiring a new clinician” to help students head off panic attacks and other episodes.

Most but not all SPARK projects address health issues and help develop drugs and treatments. Since its launch five years ago, SPARK-VT has funded 16 companies, university officials said. Two start-ups and another three potential start-ups owe at least part of their existence to the competition, and researchers affiliated with the program have been awarded six patents and have 36 patent applications pending.

Richard Galbraith, Vermont's vice president for research, said the university for years was “relatively introspective in terms of the work that was done.” That has changed over the past two decades. "It doesn’t really make sense” to be so insular, he said. “You have to work on behalf of society writ large.”

A physician and professor in the university’s department of medicine, Galbraith said the primary purpose of SPARK is to get research “out of the university and into the world so it can be useful.” Recent proposals run a wide gamut, from an emergency hypertension drug to improved propulsion systems for microsatellites, better ground-penetrating radar for urban infrastructure and, perhaps most notably for Vermont, an improved system for nurturing and tapping maple syrup.

Regarding maple syrup, Galbraith noted that the traditional way requires waiting until a tree is 80 to 100 years old, then tapping it each spring. But that takes a long time and a lot of space -- and may not be sustainable in a time of climate change.

An alternate approach involves growing lots of little maple saplings, just a few feet tall, and utilizing a kind of suction system to harvest sap.

“You can plant these trees one or two feet apart,” Galbraith said, noting that the approach is still in the experimental phase.

Ryan McDevitt, a UVM-educated mechanical engineer and onetime research assistant whose company, Benchmark Space Systems, is developing propulsion systems for small satellites, said the company has developed 3-D printing technology that can produce titanium materials much more cheaply, without a huge manufacturing infrastructure. It joined the competition this year.

Their system uses minuscule amounts of chemicals ejected precisely and efficiently to help the satellites perform “very small rotations” and course corrections. Benchmark, located in South Burlington, Vt., near the university, now has five full-time employees and customers on three continents. SPARK funded their work in 2016, which helped develop both the hardware and software. It also allowed them to bring in a co-founder and consult with others in the field.

McDevitt recalled that one of the SPARK panel members flatly told Benchmark their pitch was “rough,” but that he saw the value in the product. He ended up becoming one of their first investors.

Rob Althoff, a neuroscientist on the UVM faculty since 2006, said SPARK helped him and a group of colleagues “get out of the academic mind-set” and into one that helped them consider how their work might benefit real-world clinicians.

“I think academics in general don’t have that mind-set,” he said.

Althoff co-founded Wiser Systems, which is developing a tool to assess the near-term risk that a patient in an emergency room or other medical setting might commit suicide. They applied to SPARK in 2015, got funding in 2016 and are using the funding to work out a commercialization plan.

It’s actually quite simple, amounting to a short electronic questionnaire, accessed via iPad, that hospitals can use to screen patients who show up in the ER. Even if a patient has never told someone he or she is depressed or suicidal, the questionnaire can replicate the kinds of questions a psychiatrist would ask, shifting the questioning as replies are offered.

“It’s not just weighing risk factors, but trying to predict what a psychiatrist would say if they’re sitting in front of the patient,” Althoff said.

The assessment takes just about a minute to complete and can tell a clinician whether a patient has a low, moderate or high risk of suicide. “We really want to build tools that are going to be able to be used,” Althoff said.

All the same, he said, he’s not planning to leave UVM, even if the tool succeeds.

“The idea was never to have this be my exit strategy,” he said. “The idea was to have the stuff that I’m doing make a difference in the real world.”

He added, “I don’t have the desire to make this my job -- I have the desire to make sure that this gets into the hands of people to save lives.”

Galbraith, UVM's vice president for research, said the worry that faculty might take their venture capital with them and leave the university is but a small consideration -- it’s rare that scientists become CEOs, he said. Most investors want “a real CEO,” preferring that the developers remain advisers.

“We’re not worried about losing all of our scientists,” Galbraith said. But he said the SPARK process has changed the way the university looks at its mission: “You can’t be an isolated ivory tower,” he said. “You have to be part of society.”