You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Chris Burns-DiBiasio, the first lady at Ohio Northern University, decided not to continue her administrative career when her husband, Daniel A. DiBiasio, started his career as a university president two decades ago. She has carved out a volunteer role.

Ohio Northern University

College presidents’ partners and spouses aren’t all wives hosting receptions in the president’s house.

Many work jobs outside of their role as presidential partners. A growing number are men. And many say the expectations placed upon them by a college or university influence their spouse’s decision to work as the institution’s president.

A new study from University of Minnesota researchers examines the role of the presidential spouse or partner at a time when it is becoming increasingly complex and challenging. Researchers called the survey, which was released Monday after being presented at the Council of Independent Colleges’ Presidents Institute last week, the “largest and most diverse known sample of presidential partners to date.” The results of the study, which involved the leaders of public and private colleges, were earlier presented at a CIC meeting.

Presidents’ partners reported high levels of satisfaction in their roles -- 84 percent said they found their roles satisfying, very satisfying or extremely satisfying. Yet they also said being a presidential partner brings sources of stress and struggle. Expectations are often unclear, and presidents’ spouses are frequently thrust into the public eye.

“I think it’s a more interesting and demanding role, if you will,” said Darwin Hendel, an associate professor of higher education at the University of Minnesota and the survey’s principal investigator. “Certainly, in previous decades, the role focused a lot on entertaining and social kinds of responsibilities, but I think increasingly as the role of a president has become much more complicated and multidimensional, so too has the role of presidential partner.”

Researchers noted key differences in the experiences of presidential partners who are women and those who are men. Expectations placed on partners were noted as being “remarkably different” by gender. Male spouses of presidents were much more likely than female spouses to report having no responsibilities for the college. Women were less likely to report employment outside their role as partners. Women were also more likely to reduce their outside work or quit their jobs when their partners became a president.

The survey team did not set out specifically to study a breakdown between men and women, however. Their work grew out of an effort by University of Minnesota University Associate Karen Kaler, who is the spouse of the university’s president, Eric Kaler. She sought to update a 1984 survey of partners led by a former University of Minnesota presidential spouse, Diane Skomars, who was married to the university's former president, C. Peter Magrath. Karen Kaler eventually connected with Hendel and with Gwendolyn Freed, who is chief development officer of the university’s Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs and who was advised by Hendel on her Ph.D.

Still, the research team found that their spouse survey was the first to have enough men responding to draw statistical comparisons by gender, Hendel said. Twelve partners reported being in same-sex relationships, which survey authors wrote was not a large enough sample for reliable comparisons with other groups.

“We did a lot of comparisons based on whether the institution was public versus private, whether it was located in the North or other parts of the country, size of institution,” Hendel said. “The only variable which turned out to have statistically significant results for several of the items was, in fact, gender.”

The survey received responses from 461 spouses and partners of college and university presidents and chancellors. A total of 349 presidential partners in the survey said they were female. Another 77 said they were male, and one identified as “other.” (Thirty-four respondents chose not to state their gender.)

The average respondent age was 58.8 years, and their partners led institutions that were split 55 percent private and 45 percent public. Nearly all respondents were white -- 87 percent. Just 6 percent were African-American, and 3 percent were Asian/Pacific Islander.

The median amount of time the respondents' partners had held presidential roles was six years. The median number of years surveyed partners have been married or in a committed relationship was slightly more than 30.

Uncertain Expectations

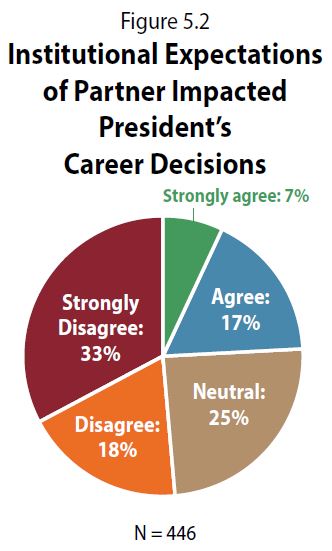

One of the survey’s most notable findings centered on how partners’ roles influence presidents’ decisions to take or remain in their jobs. Almost a full quarter, 24 percent, of partners believed an institution's expectations for them had influenced a presidents’ decision to accept, decline or step down from a position.

Asked how institutions could have eased the transition for the partner or spouse, many respondents said institutions could have clarified expectations placed on spouses. But almost as many said nothing could have been done. The number of respondents giving each answer was 84 and 78, respectively.

Pamela Gunter-Smith was reluctant at first to have her husband, J. Lawrence Smith, participate in the interview process for her presidency at York College of Pennsylvania.

“I didn’t want him to get overly involved,” she said when speaking at the CIC Presidents Institute, “at a time when we were still figuring it out.”

But it soon became apparent trustees were interested -- York College had never had a male presidential spouse. So Smith was included in some final interviews, asking what expectations would be placed upon him.

Even so, becoming a president’s spouse was still a learning process. Some unexpected questions came up -- the president’s spouse has traditionally joined the local Women’s Auxiliary, for instance, something Smith did not do.

In their report, researchers noted the high levels of satisfaction in the partner role -- 84 percent -- which broke down with 16 percent of respondents saying they were extremely satisfied, 36 percent saying they were very satisfied and 32 percent saying they were satisfied. That seemed to indicate that partners used their interests to create a partner role they found meaningful in the face of ambiguity, researchers wrote.

“In a sense, expectations are kind of an elephant in the room,” Hendel said. “They’re there. They affect a lot of decision making, but they are never particularly well articulated, and it’s also the case that I think it would be unwise for an institution to be too specific about the expectations in order that the individual develops some clarity and crafted positions which meet his or her needs. So there are all kinds of dilemmas and conundrums here, and there’s no one right answer.”

One presidential spouse who spoke at the CIC Presidents Institute described building a volunteer position as director of community relations. Chris Burns-DiBiasio is the first lady at Ohio Northern University. She decided not to continue her career as an administrator when her husband, Daniel A. DiBiasio, started his career as a university president more than 20 years ago. Their children were of school age.

Today, Burns-DiBiasio has been involved in numerous university activities and also fills community roles like serving on the Board of Directors for the Lima Symphony Orchestra. She recommends that spouses who want to craft volunteer positions create contracts to address specifics with their college or university.

“I’ve been very satisfied in my role,” she said.

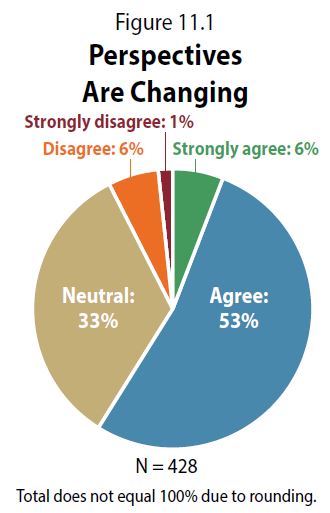

The University of Minnesota survey also showed that presidential spouses believe that attitudes are changing about their role. Asked whether they agreed with the statement “perspectives are changing with regard to the president/chancellor’s spouse/partner in higher education,” 53 percent agreed and 6 percent strongly agreed. Just 33 percent were neutral and 7 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed.

There were, however, complaints that progress was too slow or dependent on specific institutions.

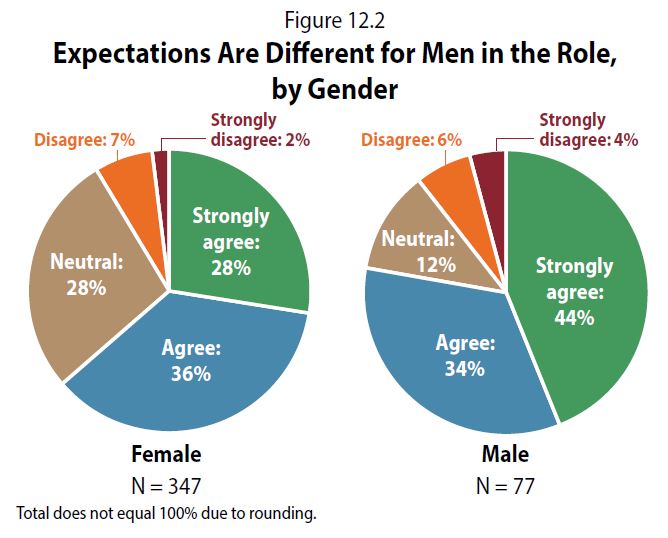

Respondents clearly felt that expectations were different based on a partner’s gender. Asked how they felt about the statement that institutional and societal expectations are different for male partners than they are for female partners, 35 percent of respondents agreed, and 31 percent agreed strongly. Just 7 percent disagreed, and 3 percent strongly disagreed. Men agreed more frequently than women.

“Very often respondents, both male and female, would respond that their perception was that females were often expected to take more traditional roles or more responsibilities: hosting, supporting the spouse, cutting back other pursuits to make this a more central part of their lives,” Freed said. “Whereas males, the perspective was that males are less often expected to take an active role in campus life.”

More than half of female partners reported being very involved or extremely involved in their institutions -- 58 percent. Just 30 percent of men were. Meanwhile, 27 percent of men were minimally involved or uninvolved, versus 12 percent of women.

Employment Matters

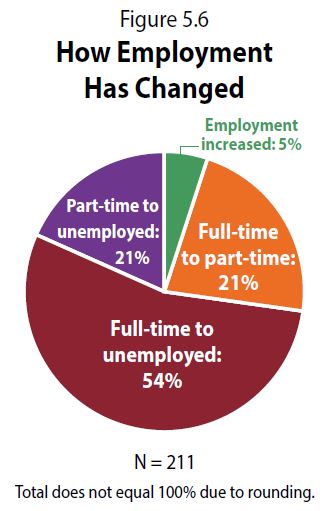

The survey also asked partners if they changed their own employment status as a result of their partners becoming presidents. Half said yes. Of those who said yes, three-quarters are now unemployed and 21 percent went from full-time work to working part time. Only about 5 percent increased their employment level.

Almost three-quarters of partners (74 percent) said they carry out informal activities, filing an unpaid role. Only 9 percent reported having a job description for an unpaid role. Another 12 percent are paid for their role, and 5 percent have no responsibilities as presidential partners.

Here, too, gender was a dividing line. More men reported no responsibilities at a college or university than women, 14 percent compared to 3 percent. More women had paid positions than men, 13 percent to 8 percent. At the same time, women more often reported taking on informal responsibilities in an unpaid role, 75 percent to 68 percent.

Other Findings

Partners who reported having a role that was formalized with a job description and financial compensation reported the most satisfaction in their roles.

Partners were more involved in institutions with an official residence. But they weren’t more satisfied in their role as partner. Most residences are used for fund-raising -- 27 percent of partners said they entertained more than 1,000 guests per year in an official residence. Entertaining in the official residence was more frequent in the new survey than it had been previously. In 2016, 54 percent of spouses said half or more of the events at the presidential residence were concerned with fund-raising. Just 39 percent said the same in 1984.

When respondents were asked about concerns, they showed remarkable consistency compared to surveys from the past. Worry about the effect of pressure on the president was the top concern cited by respondents, as it was in previous surveys in 1984 and 1977. Too little time with a spouse was second in all three surveys as well. Unpredictable demands taking precedence over a spouse’s own activities came in third.

“I was really struck by how, no matter female or male or at institutions large or small, public or private, the partners have a lot in common through lived experiences,” said Karen Kaler, the survey researcher and University of Minnesota spouse, in an email. “I hope other partners will read the report and experience a sense of camaraderie. Some of us experience this through association partner groups, but others don't have that experience, and I hope they will find the report to be a source of support.”