You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

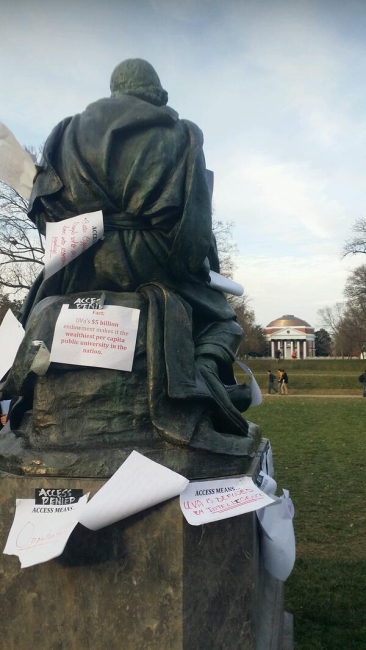

Some students feel U.Va. has turned its back on them by curbing a program to help low-income students.

Restore AccessUVA

Instead of guaranteeing that poor undergraduates can get through college debt-free, the University of Virginia decided it’s going to make low-income students borrow up to $28,000. That’s still a good deal, university officials say, for four years at one of American’s top public universities.

The changes, which take effect for incoming students this fall, have caused uproar on campus and raise questions about whether any good deed can stay funded.

By shifting burdens onto low-income students, the university can save $10.3 million a year in new costs by 2018. That's real money at a time when U.Va, like most public colleges, knows that state support is limited. But at about the same time the change was announced, it had just finished a $12 million squash court and planned to beef up its marketing budget by nearly $18 million -- raising questions for critics about whether the university really needed to change its aid policies.

A decade ago, U.Va. looked to shuck what its own consultant recently called its “elitist, preppy and homogeneous” culture and enroll more low-income students by offering them a full ride. The move came as elite private colleges were trying a similar approach, finding that telling low-income students they qualified for generous aid packages didn't have nearly the impact as saying simply that if their family incomes were below certain levels, they could come without paying or borrowing.

The Virginia policy worked: applications from low-income students quickly rose from 702 in 2004 to more than 2,500 in 2012, and the program, known as AccessUVa, took off. But instead of keeping it up, the public university is scaling back AccessUVa because, the university says, it has become too expensive.

How a Program Changed U.Va.

The university is ending a no-loans policy for the lowest income students. Since adopting the policy in 2004:

- The proportion of undergraduates who qualify for need-based financial aid has increased from 24 to 33 percent.

- The percentage of undergraduates eligible for Pell Grants has increased from 7.8 percent to 14.2 percent.

- The percentage of low-income students has grown from 6.5 percent to 8.9 percent.

Internally, at least one board member has sharply questioned the university’s priorities.

In an email to members of the university’s Board of Visitors, a board member (and former chairwoman), Helen Dragas, said that after looking over a draft of the university’s long-term spending priorities, she found a new $17.5 million line item for advertising and communications but the same plan was “sadly” silent on new university money to aid low-income students through AccessUVa.

"What does this say about our priorities?” Dragas wrote in an email obtained by Inside Higher Ed (which was among documents first reported on by The Daily Progress).

Likewise, the student newspaper noted that while the university is cutting AccessUVa, officials had other priorities – “most damningly, a $12.4 million squash court.”

Outside (Paid) Advice

Even the university's own consultants -- while urging change -- noted that the impact of such a change could be negative. The university paid for a consultant’s report that warns U.Va. it will lose qualified and diverse of out-of-state students if it made significant cuts to its financial aid package.

“If U.Va. were less generous with needy students, it would lose significant numbers of them,” Art & Science Group told the university in April. The consultant advised Virginia to create a new mix of aid packages so it could “conduct careful experiments” on price points for needy students.

In August, the university announced it would force new AccessUVa students to take out up to $28,000 in loans starting this fall.

In response to questions about the role of the Art & Science Group's recommendations, university spokesman spokesman McGregor McCance said in an email, “You should know as well that the program changes are not part of ongoing ‘careful experiments’ on low-income students.”

Though the university has recently portrayed cuts to AccessUVa as somewhat inevitable changes to a program that’s grown from an $11 million item to $40 million item, documents obtained from the university show that U.Va. officials have talked for more than a year and a half about cutting AccessUVa as part of a larger effort to reshape the university’s admissions and financial aid practices.

At a board retreat that summer, dean of admissions Greg Roberts gave a presentation that suggested the university could move away from its approach to need-based aid – which he called “clear, clean and equitable” — to a policy that would “leverage our aid dollars while adopting the most strategic and institutionally advantageous admission policies.”

“Nationally, peers are pursuing admission and aid policies that target our best applicants,” he wrote. “During a period of economic decline, our institutional aid budget is strained with more students requesting need-based aid.”

In an interview last week, Roberts said his comments were meant as a primer for the board on “enrollment management,” the set of practices universities have used to tweak their admissions and aid policies to bring in what they – or magazines such as US News & World Report – consider desirable classes of students.

“The hope was that U.Va. would maintain the strong financial aid program we had in place, and it was not an effort to shift around resources to move away from need-based in order to move in favor of, say, more merit,” Roberts said.

But when the board approved cuts to AccessUVa last summer, it said it could lessen the rising costs by $10.3 million per year by 2018. Of that avoided cost, officials wanted to use $2 million to award merit aid to “offset the impact on socioeconomic diversity” from the AccessUVa changes. Merit aid, in contrast to need-based aid, does not necessarily go to the lowest-income students.

McCance said the cuts to AccessUVa – which he pointed out don’t cut funding for need-based aid but rather curbs its “rapidly escalating” costs – is not tied to any strategy to raise rankings or to increase merit aid.

“U.Va. offers very little merit aid and is committed to providing 100 percent of demonstrated need for students,” he said.

Despite Roberts’s presentation to the board and some modeling by Art & Science Group, which point to a broad rethinking of U.Va.’s pricing and aid strategy, McCance said the university isn’t trying to reshuffle its priorities for aid away from low-income students.

“The AccessUVa changes are a response to the dramatically escalating program costs, and an interest in putting the program on a more sustainable path for the future, while still permitting the University to operate admission on a need-blind basis and still meeting 100 percent of demonstrated student financial need,” McCance said. “What the university is doing more of today is emphasizing philanthropy for financial aid. The top three priorities for our fund-raising efforts are financial aid, the faculty and preservation of the Jeffersonian Grounds, including the Rotunda.”

The student newspaper questioned that line of thinking, arguing donors might not want to pay for scholarships, and accused the university of sending AccessUVa to an uncertain future.

“Financial aid is too important to be left to donors,” the paper wrote. “The responsibility for student access lies with the institution — not with the whims of the wealthy.”

The expense for AccessUVa has grown quickly, particularly since the recession. In 2008, the program cost $59 million – of that, about $21 million came straight from U.Va.’s operating budget. By 2012, the program cost $92 million a year, with $40 million coming from the university's budget. Part of the growth is the due to the economic downturn, which created more low-income families in general, and part of it is the success that AccessUVa has had attracting low-income students in particular.

“In some cases you become the victim of your own success if you think about it that way,” Roberts, the admissions dean, said.

When it was created in 2004, AccessUVa provided loan-free educations for low-income students. After the changes take effect this fall, low-income students from Virginia will need to take out loans of up to $3,500 a year, or $14,000 for four years. Low-income students from out of state will have to borrow twice that.

Roberts, the dean of admissions, said his greatest concern is the potential loss of low-income students from outside of Virginia.

“We believe it has been and continues to be one of the most robust financial aid programs in America,” McCance said, noting that wealthy private colleges but few publics have anything like it. “Through this program, the university is dedicating more institutional funds than at any time in its history for student financial assistance, and we are assisting more students today than at any time.” The university has need-blind admissions.

UNC Isn't Backing Away From No-Loans

But the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill – Virginia’s recent top competitor for out-of-state students – has a loan-free program for low-income students that it plans to keep, despite the strains it’s placing on the university budget. That aid program is as generous as AccessUVa has been, but North Carolina officials are committed to keeping the program intact and see a far greater benefit than just numbers.

The Carolina Covenant was created a decade ago to send a clear message to high-achieving low-income students: if you can get in, you can come, debt-free.

“We knew that low-income families would understand what we meant when we say, ‘no loan,’ or ‘debt free,’ ” said Shirley Ort, UNC-Chapel Hill’s associate provost and director of scholarship and student aid.

The program has, like AccessUVa, grown. It costs about $50 million a year, about half of which comes from the university or private grants. Demand can be unpredictable. This fall, for instance, 100 more students qualified for the Covenant than the year before. All told, some 2,200 Chapel Hill students are covered by the program and can graduate debt-free, although they are asked to do work study.

“It is a stretch and it is hard and it requires some hard decisions at the university to decide to keep going,” Ort said.

Despite the cost, Ort said the institution is committed to keeping what she called an easy and positive symbol of something enduring: an accessible education for everyone. Any change to the program, she said, would harm that message.

Ronald Ehrenberg, the director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute, said other institutions that have backed away from generous aid packages have generally tried to protect the lowest income students.

Virginia has not done this because even the poorest of AccessUVa students might have to take out up to $28,000 in loans – which will cost them about $290 a month over 10 years to repay after they graduate. U.Va. points out its graduates earn good paychecks.

“Public relations-wise, I think this is a very costly decision for probably not saving a lot of money,” Ehrenberg said.

In North Carolina, Ort said Carolina Covenant costs only about 15 percent more than a typical mix of need-based aid.

Students at Virginia who received AccessUVa’s loan-free deal are deeply troubled by their administration’s decisions to begin making students go into debt.

Already, according to a consultant’s report paid for by Virginia, the university has a “polarizing” campus culture that can “turn off many desirable prospects.”

Stephanie Liana Montenegro Nunez, a U.Va. student who expects to graduate later this year, said some students are worried that changes to AccessUVa will turn the university back into a “very elite” and “non-inclusive” place.

“The fear is that AccessUVa was the little light in the sky that was working toward making things better, and it was making things better slowly, but it was the right approach,” Montenegro Nunez said.