You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Now it's all up to Judge Allison Burroughs. Thousands of pages of documents have been submitted to the federal district court judge in the lawsuit charging that Harvard University's admissions policies favor black and Latino applicants at the expense of Asian American applicants.

Whatever Judge Burroughs rules, an appeal is expected, likely to the Supreme Court, which, with the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy, lacks a majority of justices with a record of supporting the right of colleges to consider race and ethnicity in admissions.

Already both sides -- and others in higher education -- appear to be thinking both about the appeal and the public debate about colleges' admissions policies. The case in theory is about Harvard alone. But if it is appealed and results in a new federal standard for consideration of race (or a ban on such consideration), it could affect most colleges. While only a few have Harvard's level of admissions competitiveness, many colleges with competitive admissions do consider race and ethnicity, and many other colleges consider race or ethnicity in financial aid or enrichment programs.

Beyond the legal issues, there are the questions about politics (the Trump administration has embraced the lawsuit) and the image of higher education, in particular among Asian Americans. Inside Higher Ed's surveys of high school counselors and college leaders have revealed serious concern -- even among those who back affirmative action -- about the distrust of many Asian Americans in the admissions process.

Others fear that the arguments made by the plaintiffs -- many of which rely on comparisons of average test scores and grades of various groups of students -- have left the public more confused than ever about how top colleges admit students.

In the holistic admissions process they use, and which Harvard has defended, students are judged on the totality of their records (including, at some institutions, race, ethnicity, athletic ability, alumni status and other qualities) and are not admitted based solely on a rubric of admission for those with an SAT score above X and a grade point average above Y. Many people unfamiliar with the concept of holistic admissions assume there is a formula (or should be) such that it is clear who should be admitted.

Christopher L. Eisgruber, president of Princeton University, used his State of the University letter this month to respond to the comments he is hearing about the Harvard case.

"I wish, as do many others, that as we searched for merit and talent, we no longer had any need to take race into account," he wrote. "When I first encountered the Supreme Court’s initial affirmative action decision, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, as a high school student in the 1970s, I would not have believed that the issue would remain hotly contested more than 40 years later. I instead hoped and expected that our country would act quickly and forcefully to eliminate racial inequalities in schooling, in policing, in health care, in housing and in employment.

"Had America done so, we would not need to consider race today when seeking the talent and perspectives essential to Princeton’s teaching and research mission. But America’s quest for equality remains unfinished, and so we at Princeton, like our counterparts at other leading research universities, continue to believe that we can best find the students who will make a difference on our campus and beyond if we consider race as one factor among others in a holistic admission process."

He added, "The trade-offs in the admission process are complex and difficult, but this much is straightforward and singularly important: every single student on this campus is here because of merit. All of our students are here because we have made a judgment, on the basis of exceptionally demanding standards, that they have what it takes to succeed at Princeton, to enhance the education of their peers, and to use their education 'in the nation’s service and the service of humanity' after they graduate. That is true of our undergraduates and our graduate students. It is true of our athletes, our artists, our legacies, our first-generation students and our students from every state and every country represented on this campus. They all have the talent needed to benefit from the transformative education made possible by our superb faculty and staff."

Eisgruber noted that a similar complaint to the Harvard lawsuit had been made against Princeton with the Education Department's Office for Civil Rights, and that OCR cleared Princeton in 2015. But it may be worth noting that OCR's analysis was based on Supreme Court rulings in cases involving the University of Michigan and the University of Texas at Austin -- rulings that the plaintiffs in the Harvard case hope will be reversed by the current litigation.

What the Judge May Be Eyeing

It can be dangerous to read too much into brief remarks by a judge in the final hearings in a complicated case. But that doesn't mean observers don't pay attention to those remarks. The Associated Press quoted Judge Burroughs as pointing out potential vulnerabilities in both sides in the case.

“They have a no-victim problem,” Burroughs said, referring to the failure of Students for Fair Admissions to introduce direct testimony from a rejected Asian American Harvard applicant who could point to Harvard's admissions policies as discriminatory. But Judge Burroughs told Harvard, "You have a personal rating problem," referring to the part of the admissions process where personal qualities are considered, and where the odds of Asian American applicants with stellar academic qualifications fell, according to data presented at the trial.

On the issue of an Asian American witness, the issue raised by Judge Burroughs points to a difference between this case and others that have challenged the right of colleges to consider race in admissions. From Allan Bakke, who was rejected by the medical school at the University of California, Davis, to Abigail Fisher, who was rejected for admission as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin, these cases have been based on individuals who claimed that they were rejected because of their race, and their stories were a key part of the evidence. Bakke and Fisher are white.

Students for Fair Admissions says it is suing on behalf of many Asian American students, but there has been much less focus on (and no testimony from) an individual who was rejected. It is unclear how crucial an issue this will be, but Harvard's lawyers have said from the start that they do not believe there is a basis for the Asian Americans to sue.

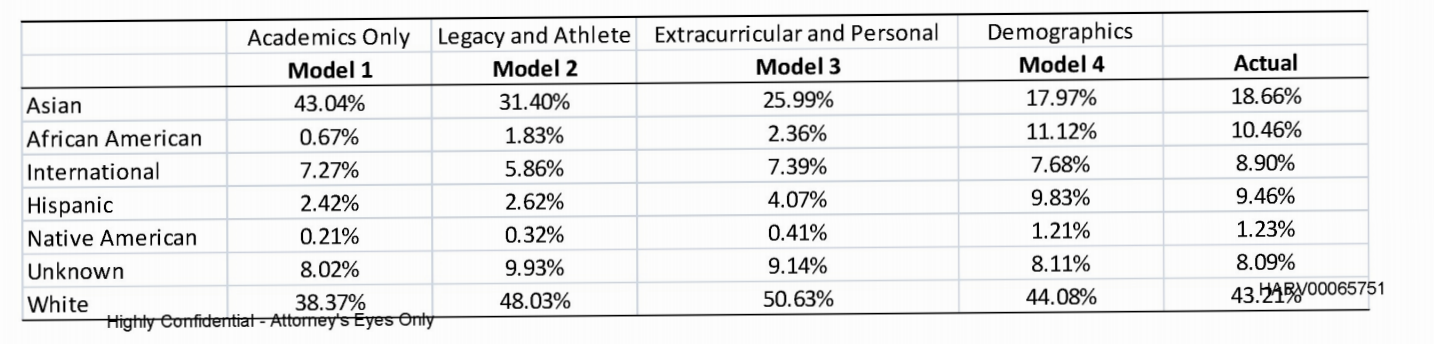

The personal ratings issue is one that has resulted in widespread criticism of Harvard -- even from some who are supportive of the right to consider race and ethnicity in admissions. The plaintiffs -- after years of court fights -- obtained documents from Harvard that modeled various considerations in the admissions process. Harvard says that the table below is flawed and inaccurate, even if the data come from the university.

But it shows how in a given year, various factors in admissions would have produced different shares of the freshman class. Consideration based on academics alone would have yielded a class with more Asian American students than from any other group. But when other factors (first status as an alumni child or athlete), then a personal rating and finally consideration of race and ethnicity are factored in, the share of Asian American slots goes down dramatically.

In its closing arguments, Harvard said that this analysis looks bad only based on a false assumption: that the key factors in admissions should always be academic. This might be true at a college where the applicants included many who could not do the work to succeed, the university argued. But at Harvard, the vast majority of applicants not only could succeed but could thrive at the university -- with high school backgrounds that would earn them admission to the vast majority of colleges and universities. In this environment, nonacademic factors may well be decisive, but that is just because there is so little difference (in pure academics) among many applicants.

"SFFA argues that race must affect the personal rating because 'African Americans and Hispanics in the top four academic index deciles have a substantially higher probability of receiving a personal rating of 1 or 2 than whites and Asian Americans,' and because the distribution of the personal rating by race and academic decile resembles that of the preliminary overall rating (which does consider race as one among many factors)," Harvard's final argument said.

"That argument reflects SFFA’s fundamental failure to acknowledge that Harvard’s admissions process is driven largely by nonacademic factors, as well as by academic factors that go well beyond the two components measured in the Academic Index. Comparing applicants’ ratings and admissions outcomes within a given decile of the Academic Index is in effect like running a regression that controls only for GPA and SAT scores; it compares applicants who are similar on those two factors but who may vary in many other ways for which the analysis does not account … But although grades and test scores are certainly important to the admissions process, excellence on those measures is more abundant in the applicant pool than almost any other measure, and even when academic strength is more broadly defined, it is more abundant than other dimensions of applicant strength."

Students for Fair Admissions zeroed in on the personal rating issue in its final brief for the court. It argued that the large shifts in the ethnic and racial makeup of the admitted class once the personal factors come into play can't be explained by anything but illegal discrimination.

"The court therefore must answer a question of great importance to the parties and Asian Americans across the country," the brief says. "Why? Why does being Asian American systematically lead to a lower rating of an applicant’s personal qualities? SFFA’s answer is that Harvard engages in racial stereotyping, a form of intentional discrimination, and that the record contains extensive statistical and other circumstantial evidence to substantiate that charge.

"Harvard’s answer (to the extent it even offers one) is that Asian American applicants simply deserve it -- they deserve lower personal ratings. According to Harvard, Asian-Americans applicants -- as a group, year after year -- compare unfavorably to their African American, Hispanic and white peers … Harvard has imposed a statistically significant penalty on Asian Americans. Unless the court is willing to find that the clear racial hierarchy of the personal rating is just a coincidence, SFFA must prevail."

A decision is expected this spring.