You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

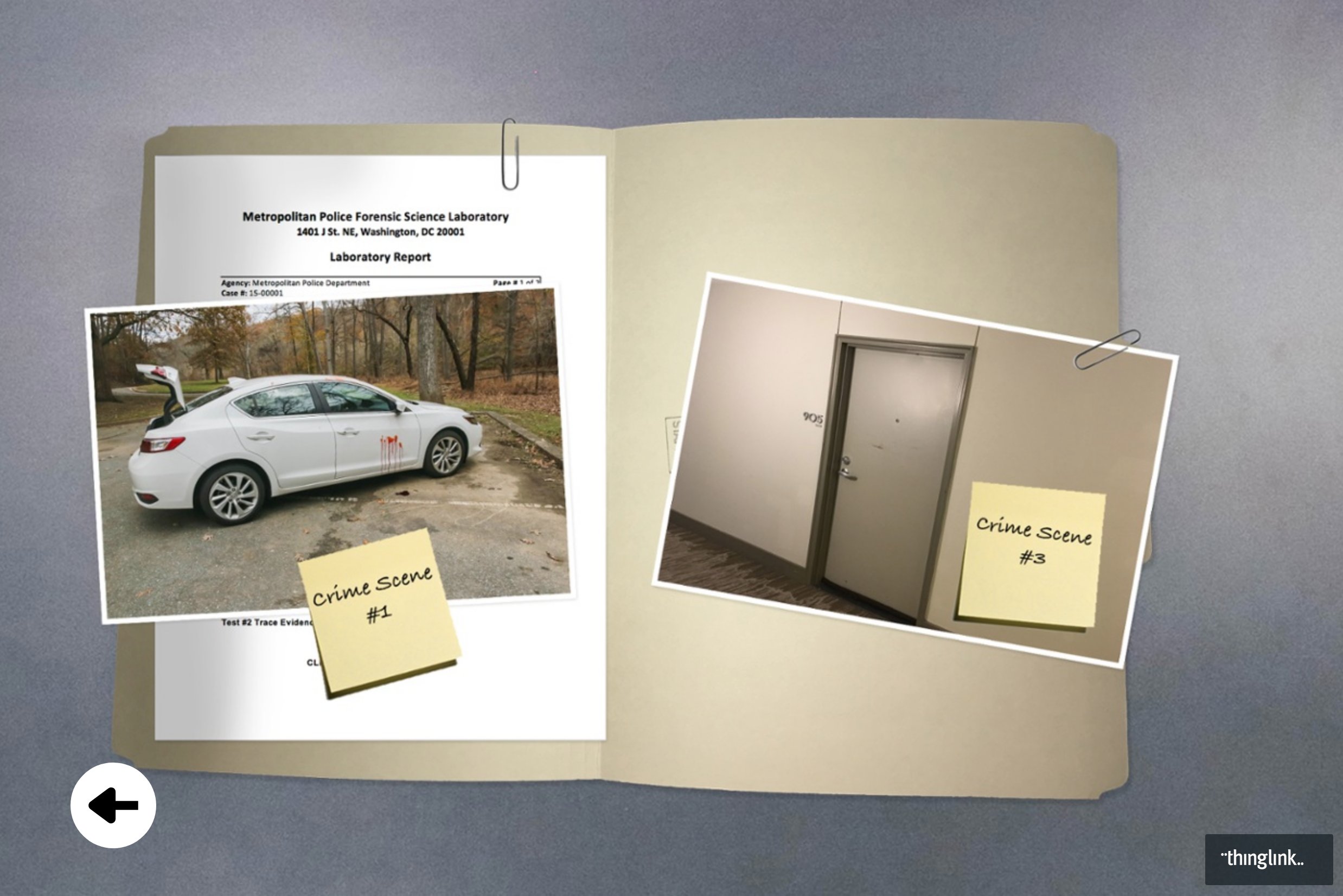

This screenshot shows the opening screen in a crime-scene simulation, in use in George Washington University's police and security studies program.

Cody House/George Washington University

Trial and Error is a recurring feature from “Inside Digital Learning” that examines the successes and struggles of technology initiatives on campuses and in classrooms. Have ideas for future columns? Send them to mark.lieberman@insidehighered.com. And be sure to comment below the story with thoughts and ideas for this institution.

The Institution: George Washington University, in Washington

The Problem: The institution's degree program in police and security studies has leaned more heavily on hybrid and online courses in recent years, giving far-flung students more opportunities to experience instruction from current and former police officers. Whether online students are participating synchronously or asynchronously, instructors felt learners were missing out on the tactile component.

The Goal: Professors turned to Cody House, the program’s designated instructional designer, for guidance on improving the learning experience. House had already been workshopping an idea to create a project or assignment that stretches across multiple courses and encourages deeper long-term learning. Eventually, he decided to try his hand at a new medium for him and the department: virtual reality.

Courses in the program often relied on popular examples of police investigations like the high-profile stumbles at the O. J. Simpson murder scene. House hoped to create a crime-scene simulation powerful enough to have the same memorable effect on students throughout their academic career.

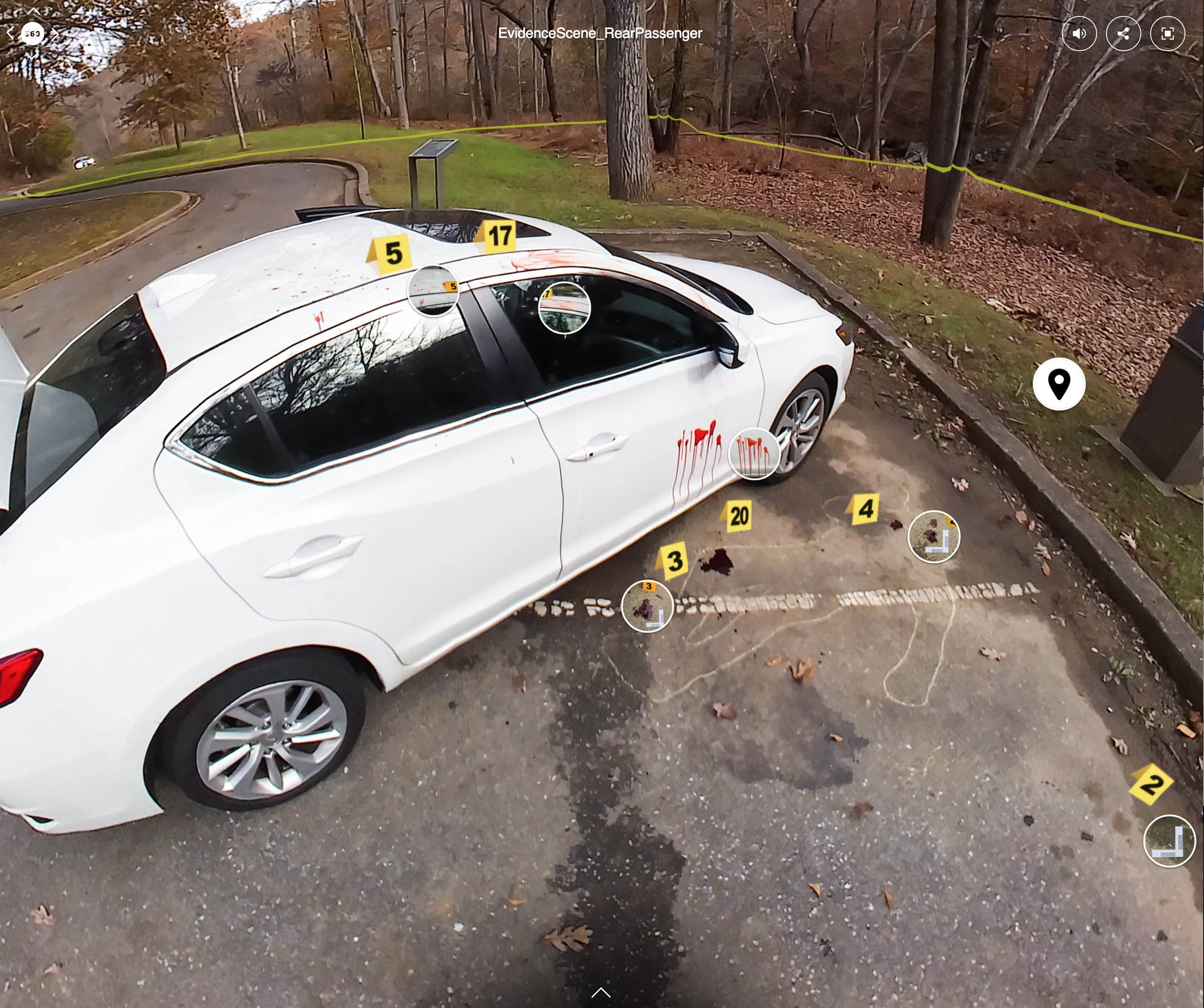

The Experiment: House, along with his videographer Drew Santorello, gradually developed the concept: a virtual crime scene and several site visits that emerge from it, along with a virtual evidence lab where materials from the crime scene come under analysis. Each scene is littered with Easter eggs -- denoted with an icon that allows students to zoom in -- that prompt discussion about the investigative process and leads students toward predetermined conclusions.

Face-to-face students access the simulation via Google Cardboard headsets purchased by the university for this project. They can also view a less immersive version on their smartphones, tablets and computers. House and Santorello meticulously constructed the simulation from more than 200 360-degree photographs of an artificial but realistic murder scene.

Upon hearing House’s plans, some faculty members appeared concerned that the simulation would amount to a video game.

Upon hearing House’s plans, some faculty members appeared concerned that the simulation would amount to a video game.

House was quick to assure skeptics he wanted to do something less frivolous.

"Early on we talked about doing a narrated, guided crime scene, with a police officer describing the evidence," House said. "But I didn't want it to look like a Dateline re-enactment."

The program director, Jeff Delinski, also wondered if the tool would have enough impact to warrant the time and money spent. But he was convinced, he told "Inside Digital Learning," when he was confident the simulation would work for multiple courses.

"I was impressed with the level of quality that came," Delinski said. "What I like most about it is it can be scaled with added features."

House and Santorello spent weeks writing a detailed “crime novel” that laid out exactly how and where the murder took place, where evidence ended up and what resulted from the investigation.

Once they agreed on the setup, the project came together quickly. They shot crime scene photos in early fall 2017, edited them for a few weeks and placed them in the ThingLink platform for 360-degree images. Students in Crime Scene Investigation and Introduction to Forensic Science began engaging with the simulations in January. Their feedback thus far has been positive, House said, but the higher-stakes test will be whether they retain, for future classes, a working understanding of the skills they gained from the simulation.

What Worked (and Why): House opted to construct his simulation out of 360-degree images because they can be less daunting to produce and disorienting to watch than 360-degree videos. The images -- which mimic the appearance of Google Street View -- also give students more flexibility to explore the virtual space at their own pace, rather than getting carried along by a video.

At the last minute, House also added outdoor audio of overhead birds and wind gusts to heighten realism.

The entire process proved far more cost-effective than House could have predicted. The Kodak PixPro camera cost $500, though it’s often on sale for $450. An iPhone app connected to the camera allows for the creation of 360-degree images. An annual subscription to the ThingLink premium platform, which hosts the simulation, costs between $120 and $150.

The other main costs came from the university’s existing site license for Adobe Photoshop, and in the pre-existing salaries for House and Santorello, who maintained their regular course development duties while pursuing what House calls a “passion project” in their free time.

House sees the existing simulation as a springboard for discussions that form the foundation of the program. When you arrive at a crime scene, what do you look at first? What are you allowed to touch? How do you decide between helpful evidence and red herrings? Where else do you look once you have leads? What questions do you ask in the evidence lab to narrow down your findings?

More from Inside Higher Ed

A virtual reality expert says the tool will soon grow more prevalent in the classroom.

VR makes headway in health care, art, history and social work.

Blogger Josh Kim interviews a virtual reality start-up founder.

Students have given the experience "glowing reviews" so far, according to House's anecdotal surveys. He's also had enthusiastic responses from faculty members.

What Didn’t Work (and Why): The first camera they tried, the Theta S, wasn't a good fit. Apps kept crashing and the device frequently needed to be restarted. “We wasted a lot of time on that,” House said

The process of editing the photos also dragged. Many of them needed tweaks in Photoshop because some elements hadn’t worked out in person -- like the addition of “police tape” around the crime scene, proper numbering of the evidence markers. But House and Santorello didn’t develop a system for editing the photos prior to diving in, and sometimes one would duplicate the other’s efforts.

They also realized later that they could have finished editing faster had they used a more sophisticated Adobe tool. But once they had started with their initial procedure, they found it too difficult to change midstream.

House is ambivalent about how much time the students should spend viewing the simulation through virtual reality glasses. This semester, students got introduced to the simulation through the glasses, and the novelty factor wowed them, according to House. But he encouraged instructors not to let the excitement around the immersive technology distract from conveying the learning material. As a designer, he’s still hoping to improve that balance.

House is ambivalent about how much time the students should spend viewing the simulation through virtual reality glasses. This semester, students got introduced to the simulation through the glasses, and the novelty factor wowed them, according to House. But he encouraged instructors not to let the excitement around the immersive technology distract from conveying the learning material. As a designer, he’s still hoping to improve that balance.

Though the simulation can be viewed on Google Cardboard, it’s not yet compatible with the mainstream virtual reality viewer Oculus Rift.

What’s Next: Two courses this semester have made use of the tool. A third one -- Criminal Analysis -- will join next January, with possibly more to follow. House hopes the simulation will eventually serve as the foundation for students’ capstone project -- perhaps a culminating assignment that requires a large case file with findings from the crime scene and a portfolio of smaller tasks from throughout the program.

“Like all good projects, it’s never going to be finished,” House said.