You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/Eduard Harkonen

The money game in higher education admissions these days is under such intense scrutiny on so many fronts that one wonders how long the sector can (and should) hold on to a financial model that has fueled more than 50 years of virtually unhindered growth. Three recent items tell a tale.

First, there was the surgical dissection in The New York Times Magazine about the competing demands for diversity and revenue generation in enrollment management. The story laid bare a dynamic well-known to those inside the gates but hidden from the general public by the often idealistic (and, unfortunately, obfuscating) promotional language of the academy.

Next came the near-unanimous vote last month by the National Association for College Admission Counseling to excise three provisions of its Code of Ethics and Professional Practice, a decision not altogether well received by the delegates but one meant to stave off the U.S. Department of Justice in its antitrust investigation into admission practices.

And finally last week, the federal district court ruling that Harvard University does not discriminate against Asian American students in its undergraduate admissions practices, a victory for the college in a closely watched lawsuit filed five years ago. During the hearings, the plaintiff presented evidence that the college had admitted a greater share of Asian American students in recent years and claimed that Harvard had adjusted its practices in response to the suit.

Each of these on its own merits could be interpreted as rational business decisions. Taken together, however, and considered in the context of a $7 billion decline in government funding over the past decade, rising levels of student debt, persistent questions about higher education’s ability to prepare students for employment and scandals that signal an ambiguous commitment to access for lower-income students, and it’s difficult not to believe that higher education is addressing its issues as one-offs, cementing public opinion of an elitist sector seemingly removed from real-world concerns.

Perhaps it’s time for a new approach, something systemic, something bold. Perhaps higher education’s leaders should bring the same dispassionate inquiry to their problems as the faculty brings to its research and teaching.

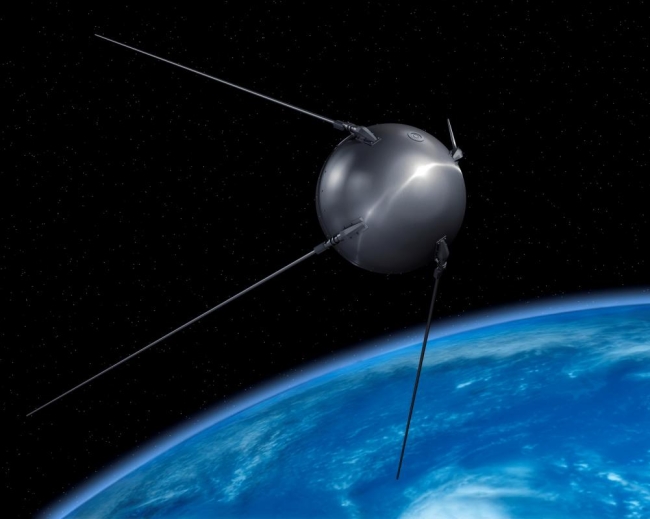

History may provide some insights. Some six decades ago, spurred by the Soviet Union’s successful 1957 launch of the Sputnik satellite and growing concerns that American scientists were falling behind their counterparts in the Soviet bloc, President Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act of 1958, “an Act to strengthen the national defense and to encourage and assist in the expansion and improvement of educational programs to meet critical national needs and for other purposes.”

The act -- informed and endorsed by industry, government and higher education -- provided a four-year program designed to strengthen education in science, mathematics and “modern foreign languages” at the elementary, secondary and postsecondary levels. It provided more than a billion dollars over four years for a variety of programs, including financial assistance in the form of loans and graduate fellowships.

The act was not without its detractors. Some institutions protested the requirement that beneficiaries complete an affidavit disclaiming belief in the overthrow of the U.S. government; such a stipulation, they said, would violate academic freedom, and the mandate eventually was repealed in 1962. But the law triggered nearly three decades of growth in postsecondary enrollments in the United States. In 1960, college enrollments among traditional-age students stood at 3.6 million. A decade later, eight million students were enrolled, about 40 percent of traditional college-age men and women, and by 1990, 13.5 million students were attending college.

While enrollments have continued to grow, the rate of degree attainment has slowed. In 1990, the U.S. was second only to Canada in the percentage of adults ages 25 to 34 that held a postsecondary degree, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. That was the high-water mark; today the proportion of that same age group with a postsecondary degree has the U.S. ranked 13th among developed nations, as countries such as Korea, Japan and Russia outpaced the U.S. This at a time when the demand for credentialed employees with the skills to work in an evolving global economy remains a critical need.

Higher education can continue to wring its hands over this state of affairs, but it might find greater traction in acknowledging that the go-go years of the past four decades are over, and instead seek coalescence around a new social compact addressing a pressing national need.

It’s more than a little disheartening to think that such an effort might require another Sputnik moment. Better for higher education to rediscover its fastball and recognize its role in ensuring the nation’s democratic ideals, a restoration so compelling that it would galvanize others to join forces.

We might begin by addressing the significant economic and educational gaps in access, attainment and advantage between the meritocrats at the top of the economic heap and those without the same opportunities to achieve a postsecondary degree. Such an effort would require a systemic rethinking of the types of preparation and credentials necessary for a new economy with new employment demands, a rededication to the sciences and the nation’s international leadership, and above all cooperation with policy makers, elected officials, industry leaders and one another.

What might a new way entail? Perhaps doubling down on the much-proclaimed value of lifelong learning, offering short-term sequenced credentials in both two- and four-year institutions. Paid internships to help more students gain the experience and exposure they need to launch meaningful careers. In-house industry training and development once graduates are employed. Collaboration in designing and funding campus facilities that help train students for jobs in crucial national industries, such as health care and technology. More emphasis, not less, on foreign language training and other international initiatives to create and sustain global cooperation.

The partisan divide between Republicans who say higher education has a negative effect on the direction of the country and Democrats who look more positively on the sector (as reported for the second straight year by the Pew Research Center) does not augur well for such an effort. Yet a 2018 New America poll showed there is bipartisan agreement in the economic value of a degree.

That’s as true now as it was in in 1958. Perhaps it’s time to address a new era of “critical national needs and other purposes.” Higher education owes the nation a renewal of its relevancy.