You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Credential Engine seeks to advance the universal adoption of transparent, open data to give people clear and consistent information that empowers them to find, evaluate and obtain the skills and credentials—and to navigate pathways across those skills and credentials—that maximize the likelihood of equitable outcomes. To support the intentional identification and publishing of key data to aid the field in assessing equitable pathways, transfer, and the recognition of learning, Credential Engine convened a broad coalition of equity-focused thought leaders, called the Equity Advisory Council (EAC).

Two of the EAC’s members, Elena Quiroz-Livanis, chief of staff and assistant commissioner for academic policy and student success at the Massachusetts Department of Higher Education, and David Troutman, deputy commissioner for academic affairs and innovation at the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, recently reflected on why the work of the EAC matters and what its recently released report and recommendations mean for their states. They talked with Cristen Moore, who facilitated the EAC as a consultant to HCM Strategists.

Moore: You both hold very demanding jobs and are asked to join many boards and councils. What about the invitation to join Credential Engine’s Equity Advisory Council intrigued you?

Troutman: The work of Credential Engine, and the considerations tackled by the EAC, resonate with the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board’s strategic plan. In Texas, we are trying to understand and support individuals receiving credentials of value, to support their economic mobility. If you look at the Census data from 2010 to 2020, you can quickly see that 95 percent of the growth in Texas is in communities of color. To ensure that we are meeting the needs of our economy in Texas, we are going to have to make sure we support all learners in Texas. That’s why one of the foundational ideas in our strategic plan aligns so well with the EAC: we have to look at the right data; disaggregate it by race/ethnicity, gender and income; and identify what changes need to be made to provide fair opportunity to all Texans.

Quiroz-Livanis: Exactly, and picking up on what David said about the right data, you have to know what to ask and when. In Massachusetts, we have an equity agenda, and to support it we set some key goals, including that “Sixty percent of working-age Massachusetts residents ages 25 to 64 will hold an associate degree or higher and an additional 10 percent of the population will hold a high-quality credential by 2030.” As we move forward and work towards providing pathways of mobility, we want to ensure all learners have equitable access to high-quality postsecondary opportunities. And we want to be intentional about encouraging students to pursue credentials of value, especially given the knowledge-based economy that we operate under. So while Texas and Massachusetts might go about this in different ways, we all want answers to the same fundamental question: What do we have to do to make sure postsecondary pathways are providing social and economic mobility to our residents and supporting the state’s well-being? And the fact of the matter is, we could use better data that help us make the improvements we need to make. So the EAC’s work immediately resonated with me, because this is what we are struggling with every day and it’s so beneficial to have a council of 16 experts help us figure this out.

Moore: The EAC has released a set of recommendations to the field about the data that all providers of postsecondary education and training opportunities should be making public, with the goal of deepening our understanding of equity in outcomes. What excites you about the recommendations?

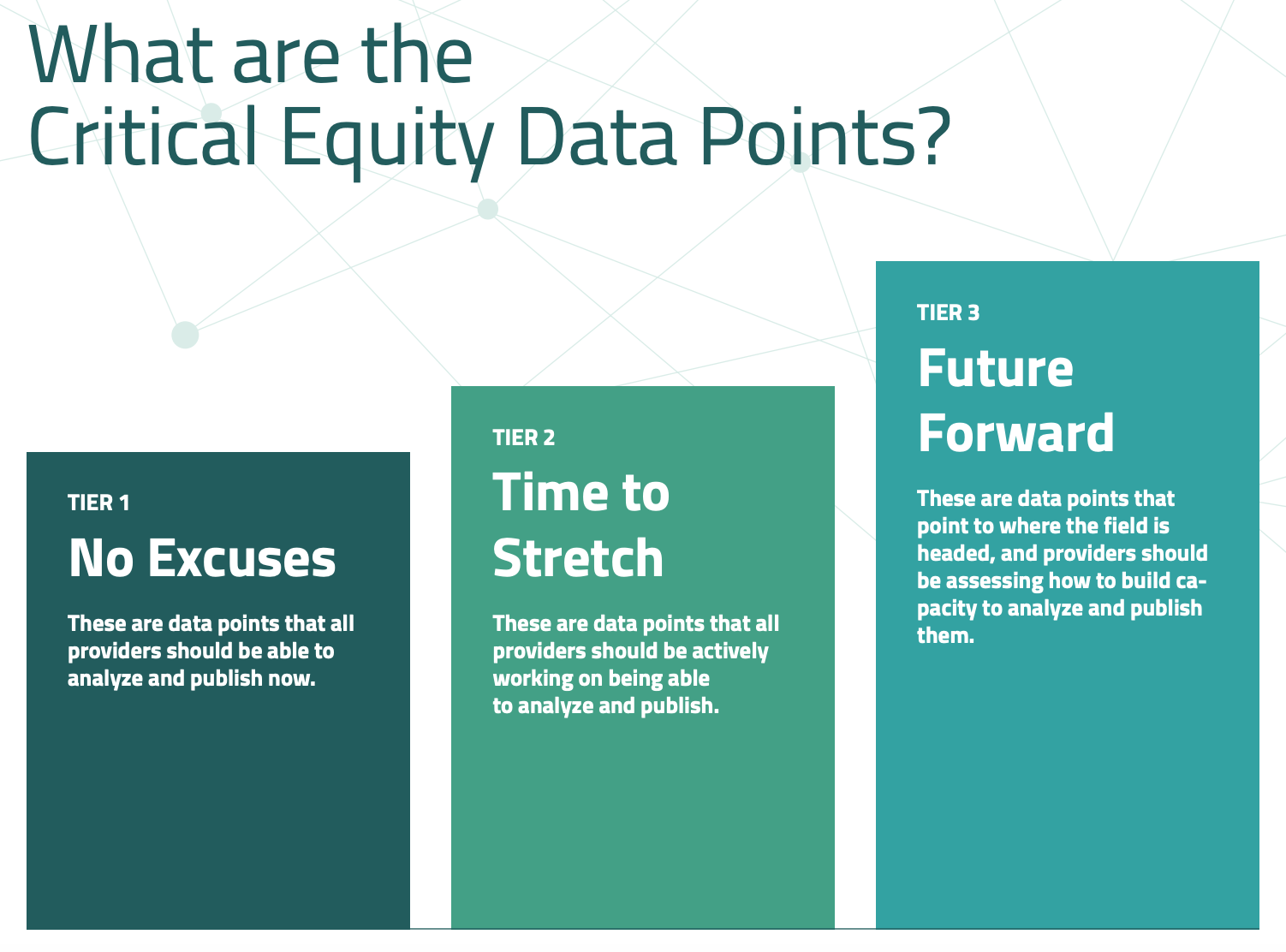

Troutman: I love the tiered approach to the recommended data. Tier 1 is foundational, naming where we have to be transparent with our stakeholders to help students, parents, elected officials, higher ed leaders and others to acknowledge the cost of pursuing a degree and the outcomes and earnings that stem from a degree. It’s the foundation of the house.

Quiroz-Livanis: Yes! The tiers are so helpful. Tier 1 is called “No Excuses”—there was agreement among the EAC that this is a floor from an equity point of view. It’s helpful to have a common understanding that this is where folks should start. Tier 1 includes things like credential completion and job placement rates. The Tier 1 data points are not that difficult, so if you don’t have access to these data, then you need to ask why.

In Tier 2, which is called “Time to Stretch,” the data step even closer to equity questions. Providers will need to add more data to provide additional context and help figure out what is actually happening. Critically, Tier 2 calls for data in areas that can help us understand whether providers are doing a good job with transfer and credit mobility, by looking at how many transfer and prior learning credits programs will apply to completion, and whether programs include related industry-recognized credentials. Without those data it’s hard to know which interventions we need to target.

Troutman: Right, and Tier 2 also helps us to start wrestling with the age we are in. It calls for things like supporting students with consumable digital records and resumes, and ensuring that stackable credentials actually work, which is a big focus in Texas right now.

Quiroz-Livanis: And then Tier 3 is aspirational. We don’t know how to collect these data points yet, but we have to start the work now. Are providers creating social mobility over time for graduates? Are learners receiving wage increases from their credentials?

Troutman: Tier 3 provides the right direction, while recognizing that collecting these data will be complicated and people need to start the work now. For providers to report on whether credits earned at their institutions were accepted and applied by a subsequent provider is hard, but we need to know that information. The underlying themes here are that student pathways are so nonlinear now, and students are engaging in lifelong learning. If students are not getting credit for their experiences at a particular provider, that must be understood and it must be transparent.

Moore: How can your state help lead with Credential Engine?

Quiroz-Livanis: This is one of the exciting opportunities before us. We have the EAC’s recommendations in hand, and so now we can systematically understand which state has made progress on what, and learn from each other. Every state is innovating in some way, and every state has opportunities. In Massachusetts, we have done a lot of work on student affordability, for example. We already have public data on tuition and fees as a percent of household income, by college and university. That is critical data that ties well into the EAC’s recommendations, and we would be happy to share with other states lessons on our work in that space. And we’d really like to learn from other states as they tackle things like support services.

Troutman: I completely agree. I can use this as a compass for understanding where we go, and also as a reality check for understanding the data maturity of the institutions in our state. And there are so many things I want to share from Texas and learn from other states. This is an exciting time—Texas just passed HB 8 on community college finance. HB 8 emphasizes funding based on things the EAC is elevating, such as students receiving credentials of value, and students successfully transferring to universities. So we will have lots to share, but that’s also just the start—we need to learn from others to make sure we are understanding whether students are taking the right courses, and whether their credits will be accepted for completion.

Moore: You two come from very different states and work in very different political contexts, and yet you came together around these recommendations. Why do you think this should resonate with everyone?

Quiroz-Livanis: We are responsible to our states for helping to create pathways of choice for social and economic mobility. If we don’t have a sense of what a high-quality credential is, we are not able to best serve our learners. We need access to reliable data and that brings it back to Credential Engine. Here is an organization that is trying to give decision-makers good data to make decisions about how to best support the well-being of all the residents of their states. That’s simply critical.

Troutman: Agreed. These recommendations should resonate with people of any political persuasion. I don’t know how students do it, honestly. Students’ lives are complicated. Prices are so high. Last year, we saw the highest increase in cost of groceries since 1979. If we can’t demonstrate the value of credentials, how can we ask students to hold off on finding a job, invest in education, potentially lose time and credits if they transfer institutions, when they are dealing with so much else?

Moore: As we come to the end of our time together, do you have any final thoughts for our readers?

Quiroz-Livanis: The recommendations also include a set of principles for the appropriate and effective use of data to support students as they navigate pathways and transfer. Credential Engine is telling the field, “These are the data you need to collect and this is how you should be using the data. If you want to be engaged in the conversation around centering equity when it comes to credentials in postsecondary education, here is a no excuses way to do that.” That’s a powerful combination that can directly support policy makers like me who want to use data to make good decisions that lead to equitable outcomes.

Troutman: I’m glad you brought up the principles, Elena. We are drowning in data in Texas. But the question is, how can we effectively use it? This is a tool we can use to make sure we can bring data to life in ways that will efficiently capture best practices and at the same time, capture the student voice and experience, because that is what we’re here for.