You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

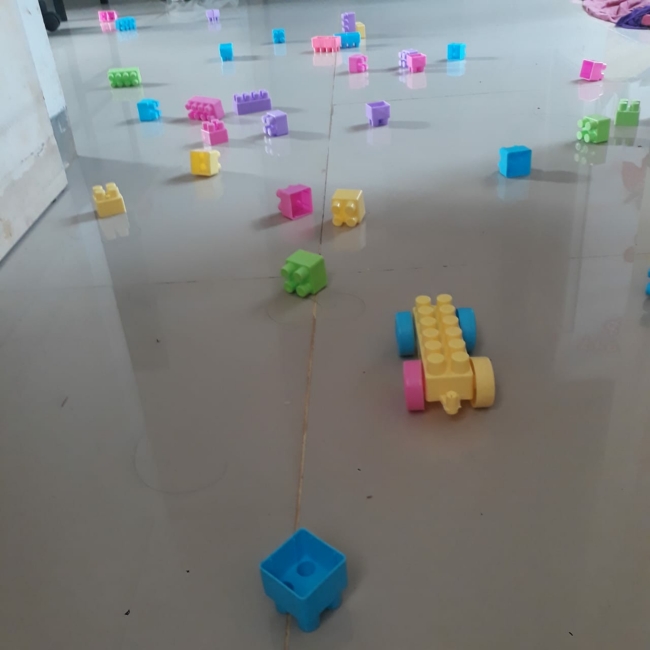

Riyanah/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The night I slept on the Legos, I thought for sure the lesson would be that I couldn’t go on like this. Couldn’t go on this exhausted, this drained, this isolated.

Months into the pandemic, I was hitting the wall. As for many families, the shuttering of in-person school was devastating for my child. Of course, those things were hard for all kids, all families. But for those of us whose children have special needs, whose children are at risk of not hitting developmental milestones because of the loss of therapeutic and educational programs, the pandemic was a different ball game altogether. It was crushing.

The last thought I had as I drifted to sleep on top of the Legos on my cold living room floor was that I couldn’t keep going like this.

That night, I had awoken to the sound of my son crying. I crept down the stairs, stood outside of his room until he quieted down and turned to head back to bed. But the bone-deep exhaustion of the past few months of 24-7 care stopped me. It was as if I was standing in cement and no longer had the energy to climb the stairs to my bedroom. I lay down on the bare wooden floor—no pillow, no blanket—and fell back to sleep. I could feel Legos under my arms, their pointy spindles poking my leg and torso, but I was out of fuel. I simply could not move.

But you know what? I did keep going, as did mothers everywhere. That includes mothers whose children have special needs, or mental health challenges, or just day-to-day run-of-the-mill “life can be hard” problems. It includes mothers who are caregivers of elderly parents, mothers of children who have complex health needs or those who struggled with long COVID while raising their kids.

Three years later, I’ve discovered that the lesson was not that I couldn’t keep going. The lesson was something entirely different, yet entirely familiar: that working moms would once again be penalized for our invisible work.

I did keep going, like all mothers. But you know what I didn’t keep doing? A core part of my job: publishing. As a mom of three, I had dealt with the invisible work of balancing children and work for years. I had done school drop-offs followed by conference calls in the parking lot. I had conducted interviews from my car. I had wrapped up a full workday; cooked dinner; played with, bathed and read to the kids; and put them to bed—only to then return to my computer for several hours. I had sat in speech therapy sessions in the middle of the day instead of taking a lunch break. Like all working moms, I had learned the tricks of invisible juggling while remaining productive.

But this new type of work—the task of balancing it all while the world collectively suffered through the pandemic—was different. Something had to give, and as an academic, that was my writing. The emotional and physical fatigue simply did not allow my brain the cognitive bandwidth to write the way I need to in order to remain competitive in my job.

As the past three years have unfolded, I’ve managed to climb back out of the hole. The bone-deep exhaustion has given way to mere tiredness, and I’ve slowly gotten back on the horse that is academic writing. What these pandemic years look like on my CV is a vacuum, a missing spot, a glaring set of omitted lines. In contrast, some of my colleagues—mostly men, by far—pumped out all kinds of publications during the pandemic.

For all our talk in higher education about diversity, equity and inclusion, we are neglecting a key group: moms. We’ve talked about the mass exodus of mothers from the workforce during COVID-19; we’ve written about how we need to allow mothers some space, some sort of exemption on our CVs from the pandemic years. But what have we really done as institutions to include this group? And where is the line on our CVs for the mothers who slept on Legos during the pandemic?

When COVID-19 first hit, I watched with panic as my husband navigated the pandemic work-child balance in a completely different way than I could have imagined doing. He brought our autistic son with him on conference calls. He allowed our son to be in the background while making unusual noises. He kept his earbuds in and calmly explained to his co-workers what was happening as he supervised our child. I thought for sure he would be fired.

I had never felt permission to have any of my children “in the background” while navigating academe. Instead I hid that mom work, kept it invisible as women are taught to do. I put my head down, didn’t reference my children, tried not to skip a beat.

But as a male, and as an established manager in his job, my husband was not afraid of this. He made that work visible. He was allowed to make it visible. In fact, he was celebrated for making the work visible. My husband’s colleagues have told me how much they admire him for his ability to juggle it all, how much they think of him as the rock-star dad, how much more they value what he does after witnessing it during the COVID shutdown.

And so our paths continued to diverge. I emerged from the pandemic having survived the balancing act of an academic job and my children, one of whom required homeschooling because he could not learn via Zoom school. My CV is not nearly what it should be; there are countless articles I didn’t write, data that are still waiting to be analyzed, grant proposals that are gathering dust.

My husband emerged as a superhero dad. I emerged as a mom who looks unproductive on paper. This is the dichotomy that we have created for women and men, the dichotomy that we’ve wanted to believe isn’t persisting into this century, but that COVID clearly brought to light.

What is it that our institutions of higher education are willing to do to support working academic mothers? We’ve made a bit of progress as Zoom meetings have normalized children popping into the background of our screens. Some institutions have allowed faculty to note a special circumstance of COVID on their CV.

But mostly our work remains invisible. We disproportionately shoulder more of the caregiver duties, but we have no place to note it, let alone celebrate it. The lesson for all of us needs to be that we must bring the reality into the light, that we need a way to talk about sleeping on Legos—not bury it the way the academy has taught us to do.