You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nuthawut Somsuk/Istock/Getty Images Plus

Being in graduate school is sometimes referred to as a graduate career. While some would argue that a career starts with one’s first job after they actually graduate, we believe that time spent in a graduate program, especially as a doctoral student and even more during a postdoctoral appointment should be considered as a career stage.

Being in the middle stage of our own careers, the four of us—Jovana, Tithi, Connor and Mark—undertook a research project where we, along other colleagues on a larger committee, analyzed 100 job ads within our field of graduate career and professional development. From that, we were able to develop a career-stage framework that can help current professionals determine where they are in their career and what competencies they should have, as well as envision the next stage and what they need in order to advance. In addition, our findings can aid graduate students and postdocs in identifying what competencies they have developed in grad school and be able to identify and negotiate better positions for themselves.

Career Stages

In virtually any profession, we commonly see three major career stages: early, middle and advanced. The early stage is usually associated with entering the job market for the first time after finishing school or college. Transitioning from a career in one field to another can also be associated with the early career stage and that may be rightfully so. Many competencies are transferable, however, and it is important to know our skills and strengths as much as our areas for growth when we are embarking on the job search journey—whether for the first or 20th time.

Middle and late career-stage borders are a little bit blurrier and harder to distinguish. For example, different higher education institutions have different hierarchies, and a title can be misleading when trying to guess the career stage. An assistant director at one institution may be the same position as an associate director at another. Similarly, an associate director may be the highest rank at one institution, while at another, the top position would be the director role.

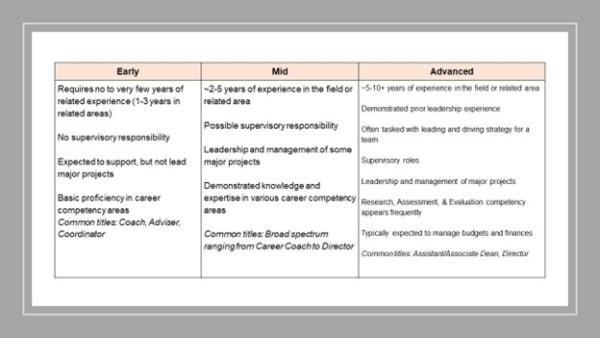

Table 1

Career Competencies

Using the Graduate Professional and Career Development Professional Competencies framework, we coded the 100 job ads we reviewed for various positions in the field of graduate career and professional development. The positions ranged from a coach to an associate dean, and we used the following competencies for coding:

- Career coaching and advising

- Communications

- Diversity, inclusivity and cultural awareness

- Financial/budgeting

- Leadership, management and administration

- Marketing/outreach and technology

- Mentoring, training, teaching and education

- Program and event administration

- Information management

- Knowledge of population, disciplines

- Relationship building/networking skills

- Research, assessment and evaluation

Using the Framework

Our analysis entailed identifying the job qualifications from required to preferred and then coding them based on the competency category they fell under. To ensure correct classification, we used code checking where everyone’s coding was checked by another group member. Finally, we categorized each role as corresponding to early, middle or advanced career stage. As shown in Table 1, the most obvious differences between the three stages include years of experience and level of responsibilities.

- Reviewing the requirements and competencies of each category to identify the stage they’re in.

- Determining the areas in which they may need to grow by identifying the skills and experiences expected for their desired position.

- Developing competencies in those areas. How to do that? There are many ways, but as an example, they can seek a position that offers the kind of responsibility that would allow them to develop a new skill—such as leadership, project management and so forth.

- Preparing to negotiate a promotion at their current position or obtain a better position elsewhere. Knowing what responsibilities are for different roles—and that we already have what it takes to fulfill them—provides the confidence to pursue a higher position (with usually higher pay).

Our project can be informative and useful to many people—from those in career and professional development field (at any stage of their career) to virtually anyone in any field—because the framework is adaptable. For those who already have a job and are interested in advancing, the career framework can be used for:

Graduate Students and Postdocs

As practitioners in the field of graduate career and professional development, we often see the difficulties that graduate students and postdocs face when they need to translate the experiences in academia into skills and competencies for a job, particularly one outside academe. What often happens is that they focus too much on the subject-matter expertise and the skills they’ve honed in studying that specific area—often neglecting and undervaluing transferable capabilities that they most likely developed throughout their academic journey.

For example, postdocs and graduate students spend a lot of time mentoring, supervising and teaching undergraduates and peers. Through teaching, they develop skills such as time and people management, evaluation and assessment. Through their research, they gain invaluable skills in collaboration, problem-solving, leadership and management.

All those are skills required in job positions beyond the entry level. The key is to translate your experiences to competencies and communicate them. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, the second most required skill is communication, right behind career and self-development. Our analysis of 100 jobs confirmed that: every single job ad we reviewed required excellent writing and communication skills. Ironically enough, those are the skills that are often taught through extracurricular programs. That’s why it’s important to look for opportunities to develop communication skills through programming such as writing retreats and oral communication skill development programs, such as the Three Minute Thesis.

In this essay, we’ve offered a high-level view of the work we’ve been doing to define better career stages and map onto them competencies required in each stage, but you can infer much more by doing a deep dive into the data. Here we provide a sample of our data, where we include the location of the position in terms of where it is housed, such as in a graduate school or at a career center. This kind of information can be useful because it provides a larger context and an indication of the kind of work that can be expected, even though it’s not in the job description.

For example, if the position you are considering is in a graduate school, you will probably need to collaborate with senior administrators and coordinate how professional development work contributes to recruitment, retention and completion. In contrast, if you hope to work in a career center, you may have more opportunities for direct involvement with industry partners. Other fields do this kind of analysis as well and provide a similar kind of framework which provides a good orientation for what can be expected beyond the job description and outlined requirements.

Graduate students, postdocs and professionals at all levels get their information about jobs and careers from many sources. But it helps significantly to know the general parameters of the various skills and aptitudes required for different types and levels of positions. In the end, our hope is that the information we shared gives graduate students and postdocs enough to begin thinking about this topic and use it as a starting point for further exploration.