You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

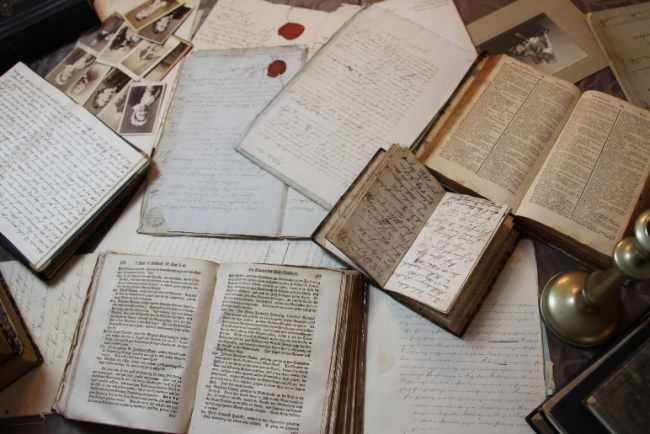

DKrue from pixabay

Since James Sweet’s column chastising historians for “presentism” appeared in the American Historical Association’s Perspectives on History magazine last August, the discipline has been engaged in a new round of soul-searching conversations about its purpose. These conversations have centered around two concerning developments.

First, American history teaching and scholarship, especially on racial justice, has been subjected to a resurgent assault by Republican politicians. These attacks are not new—instead, they form a noxious instantiation of what Robin D. G. Kelley terms “the long war on Black studies”. The current round is nevertheless notable because it has been marked by a ferocity, organization and degree of state backing not seen since the McCarthy-era attacks on academics during the Cold War.

Second, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the long-anemic academic job market in the humanities has turned apocalyptic. According to the American Historical Association’s most recent report, the 2020-21 job cycle saw “the fewest professorial job listings in history since the AHA first started keeping records in 1975.” The acceleration of the job crisis has overlapped with an unprecedented assault by Republican-led state legislatures on the institution of tenure at public universities, a bulwark of academic freedom from which most academics are nonetheless excluded.

Yet, there is a third crisis that has thus far drawn comparatively less attention and comment, but is no less concerning: a notable retrenchment in available research funding in the humanities, especially for graduate students for whom such support is essential to producing scholarship. I began my Ph.D. in history in 2009 and completed it in 2016. Here is a list of fellowships that were available to graduate students or junior faculty in the humanities at the time to fund research and study that have since ceased to exist:

- The Council on Library and Information Resources-Mellon Foundation Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources (begun in 2002; ended in 2019)

- The Social Science Research Council-Mellon Foundation International Dissertation Research Fellowship (begun in 1997; ended in 2022)

- The Mellon Foundation-Council for European Studies Dissertation Completion Fellowship (ended in 2022)

- The Whiting Foundation Fellowships for Dissertation Research and Teaching (ended in 2015 and 2013, respectively)

Other longstanding fellowships that provided general public or private support for doctoral education in the humanities have also been discontinued. These include the federally funded Javits Fellowship (begun in 1980 as the “National Graduate Fellowship Program,” renamed in 1986 as the Javits, and ended by Congress after 2011), the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellowship in Humanistic Studies (1993-2006), and the Ford Foundation Fellowship (1967-2022).

The cancellation of the Javits means that there is currently no federal funding available for general graduate-level research in the humanities. The cancellation of the Ford Fellowship ended what the scholar Diane Ravitch described as “one of the most successful diversity programs of all time,” having made a significant impact in the struggle for racial justice and equity in the academy. The cancellation of the International Dissertation Research Fellowship meant the end of a program that advocates described as a “a life-line for international students at U.S. institutions who are not U.S. citizens.”

Many of these cuts point to an elephant in the room: The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which has historically been the most important private funder of humanities research in the U.S., has recently decided to shift its focus away from supporting general, curiosity-driven research in the humanities.

Tenured faculty in the humanities also have been impacted by these cuts, albeit to a lesser degree: in 2020, the American Council of Learned Societies ended its Frederick Burkhardt Residential Fellowships for Recently Tenured Scholars, begun in 1999, and since that time has restricted eligibility to its general fellowship exclusively to untenured scholars. While there are some residential fellowships available to tenured humanities faculty (as well as untenured scholars—I myself held a Mellon Foundation-funded one at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J. between 2021 and 2022), there are not many. And critics of this residential model have noted that, in addition to their extremely competitive nature, which bars many from receiving resources, these fellowships are often practically unfeasible for scholars with families for whom moving for an academic year would be too disruptive and costly.

There is a temptation, when such circumstances are pointed out, to play down the importance of these cuts. These fellowships were always very competitive and didn’t fund very many scholars even when they existed. Haven’t resources for humanities research always been scarce? Wasn’t funding always more or less confined to students at elite universities, such that these cuts will not be broadly felt since few benefitted? And if there were few dissertation research fellowships or limited externally competitive sabbatical funding available to humanists to begin with, do these cuts really have much of an impact? Often such claims are accompanied by others—sometimes even voiced by humanists themselves—that imply a belief that humanities research is less valuable than STEM, for which there is ample and significant private and public research funding: it “makes sense” that the humanities receive fewer resources than other fields because they don’t produce “useful” knowledge and thus “don’t need” resources that are “essential” to the other disciplinary practices. We don’t need labs, it’s often said, and so humanities research can be done cheaply and without many resources (never mind that this is increasingly untrue, especially with the rise of digital humanities).

All of these claims are ultimately bad arguments against fighting for humanities research. Certainly, many of these fellowships were competitive and restricted, but that doesn’t undermine the negative impact of these cuts: something is still something, and when nearly all of it dies in the space of about a decade (2012-2022), it has a devastating effect. Moreover, the lack of support points to the broader, underlying problem: in contrast to mathematics and the natural sciences, humanists have never built a sustainable public funding model for their research. In addition to billions of dollars from private foundations and for-profit corporations, STEM fields have, for over half a century, relied on a massive government funding apparatus—encompassing not only the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health, but also funding for scientific research through other agencies such as the Departments of Defense, Energy, and Transportation. Certain social scientists, especially economists, also can access a broad range of federal funding.

By contrast, the National Endowment for the Humanities, though it does not require that applicants to its general fellowship program hold a Ph.D., states that “individuals currently enrolled in a degree granting program are ineligible to apply.” This leaves humanities graduate students with few opportunities for federal support aside from the Fulbright Program, which has awards for highly varied purposes, many of which do not include supporting humanities scholarship. Moreover, federal funding for the NEH is a mere fraction of that available to STEM. Since its founding in 1965, Congressional appropriations to the NEH have only once topped $200 million. The NSF budget alone hasn’t been less than a billion dollars since 1982. The NSF spends 17.5 times more on undergraduate research ($84 million) than the Congressional funds currently available to the NEH for individual fellowships to scholars ($4.8 million).

The demise of available private research funding in the humanities is devastating on its own, but that it has occurred absent any significant public fallbacks is even more disconcerting. Many humanists, the majority of whom do not work at wealthy universities that can support their research internally with funding and frequent sabbaticals, will struggle to sustain their research in this new landscape. Universities themselves will continue to undervalue humanists because of their inability to bring in external funding. Humanists are understandably concerned about declining numbers of undergraduate majors. And yet, as Sarah Blackwood has perceptively argued, increasing enrollments do not prevent institutional cuts to the humanities. No matter how many undergraduates decide to major in humanities fields, enrollments on their own are unlikely to generate revenue that is anywhere near comparable to the overhead that universities can get from STEM grants (the median annualized award size of an NSF grant in 2022 was almost $150,000; by contrast, the cap on NEH grants to individual scholars is $60,000).

Moreover, increasing undergraduate enrollments in the humanities without first addressing the addiction of universities to precarious, contingent workers, rather than secure, tenure-line employment, risks exacerbating the already enormous stratification between academia’s haves and have-nots. What would prevent universities from responding to higher enrollments in the humanities by hiring more adjuncts rather than tenure-line faculty?

The demise of humanities research will have far-reaching intellectual consequences as well. It may mean the extinction of many fields of disciplinary inquiry in the United States, such as the study of Sanskrit and medieval Latin, whose benefit redounds to society in spite of the fact that they only find institutional support within academia, and in spite of the fact that few undergraduate students may wish to take classes in them. There are already signs that this is happening: a recent report from the Medieval Academy warns that tenure-track assistant professorships in medieval studies are “now at the lowest they have ever been” since the organization began tracking data, and “there appears to be effectively no field of premodern Islamic Studies at the moment.” Unless study and scholarship in such fields could somehow be institutionalized outside of the university—an unlikely prospect in the U.S. given that there are few independent, non–university-affiliated humanities research institutes in this country—they will die.

Equally important, the demise of humanities research will impair the vital role of humanists in education and in shaping public discourse. As Christopher John Newfield has explained, research activity is in fact central to undergraduate education in the humanities at all institutions, even those not conventionally classed as “research” universities, because a crucial aspect of research is “the transmission and integration of new knowledge into a common knowledge base”—precisely what occurs in a college classroom.

Humanities research similarly underpins humanists’ efforts to communicate knowledge to audiences beyond the university. As Peter Jakob Olsen-Harbich has argued, a crucial part of the work of public humanities is the translation of what Abraham Flexner famously called “useless knowledge”—that is, knowledge not generated with the immediate intent of application to solving a specific problem but motivated instead by curiosity—to audiences who may not be interested in the details of its generation but for whom the knowledge itself can be profoundly meaningful and important. That public translation requires, as its foundation, a continuously available and evolving stream of “basic research.” Just as there would have been no computer chips without quantum mechanics, there could be no "The 1619 Project” without decades of academic journal articles and monographs about slavery and capitalism that were written initially for audiences of other academics, not “the public.” Without reliable funding, that stream of basic research in the humanities will dry up, impoverishing efforts to shape public discourse.

What can be done to fix this? The academic labor movement, though essential to improving working conditions, is not equipped to address the research crisis directly: labor unions deal with employment matters, not the internal division of resources within universities. Nor do labor unions have the ability to control or influence the funding decisions of Mellon, Whiting, CLIR, ACLS or SSRC—this is simply not what unions do. The movement to lobby Congress to increase the NEH and Department of Education budgets is crucial, but faces a significant uphill battle given Republican control of Congress and the commitment of influential Democrats to career-centric and technical education. It seems it will be crucial to seek more influential private funding support to replace what has been lost from the likes of Mellon, Whiting and Ford.

But whatever strategy is decided on, there must be a strategy and an organized movement to implement it. This movement needs the voices and participation not just of graduate students, contingent faculty and the untenured, but crucially, tenured faculty, who have also lost out by these cuts. It will be especially important for those at the helm of humanities disciplines—not simply the leaders of organizations like the American Historical Association and the Modern Language Association, but also influential and distinguished humanists, such as Guggenheim and Macarthur Fellows—to use their stature and voices to address this crisis. Nothing less than the future of the humanities is at stake.