You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

cuputo from cuputo

Let’s get serious: educators are burned out. Like many workers who struggle with low pay, lack of advancement opportunities and feeling disrespected, higher education faculty members struggle to keep it together because of exhaustion and the lingering impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some argue that reports of faculty burnout are misleading and tantamount to a “culture of victim-seeking.” However, that misses a critical point: burnout among faculty is a concern because many are leaving for employment in other sectors. Before things can improve, we must understand faculty members’ experiences and provide positive pathways forward.

As public administration scholars, we study how public policies are created and implemented and how public service institutions operate (e.g., governments, nonprofits or even some private sector agencies). Given public administration’s centrality in providing public services, we must find ways to address the employment and morale crises in both the public and nonprofit sectors. In February 2023, we conducted a global survey of more than 900 public administration faculty to gain insight into why faculty come to work, what universities can do to retain faculty and solutions for the future of higher education. Our findings offer three lessons for higher education institutions to consider.

Lesson No. 1: Faculty Are Exhausted and Worn-out

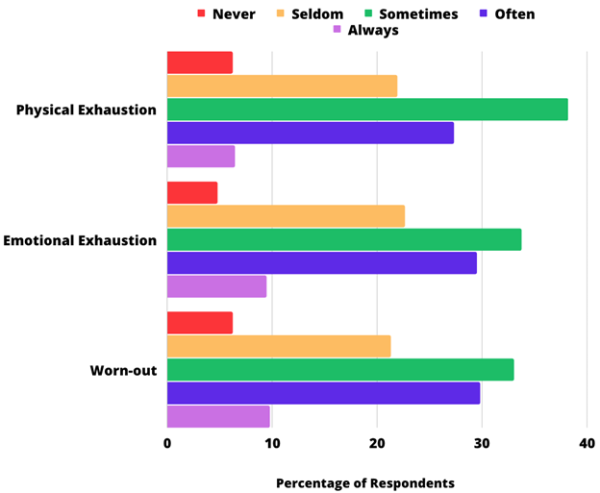

What is the state of faculty well-being, especially given the broader implications of the pandemic and concerns surrounding the global burnout crisis? We asked participants in our study about the frequency with which they experience physical exhaustion, emotional exhaustion and feeling worn-out, using a scale of “always,” “sometimes,” “often,” “seldom” or “never.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, the modal response for each of these areas was “sometimes”: 38 percent sometimes feel physically exhausted, and 34 percent sometimes feel emotional exhaustion. Thirty-three percent report they sometimes feel worn-out.

However, many faculty report “never” or “seldom” feeling physically exhausted (28 percent), emotionally exhausted (27 percent) or worn-out (27 percent).

The findings of our survey become concerning when we examine responses in the “often” or “always” categories. The findings suggest that in each category, many faculty are often or always physically exhausted (33 percent), emotionally exhausted (38 percent) or worn-out (40 percent). More than 50 percent of our sample feels this way daily.

These results are disconcerting for retention efforts for higher education and beyond. Our findings showcase that burnout is a critical concern for the academy. Burnout refers to numerous types of exhaustion (emotional, mental and physical), and it is caused by chronic exposure to stress; emotional demands; overworking; unrealistic expectations; working in toxic, unsupportive and underresourced environments; and pushing ourselves too hard without taking care of our physical and emotional well-being. Given that K-12 teachers are among the groups most commonly impacted by burnout, solutions to retain faculty are essential.

Graph 1: Well-Being

Courtesy of Sean McCandless, Bruce McDonald and Sara Rinfret.

Lesson No. 2: Faculty Most Value Being Able to Do Their Job

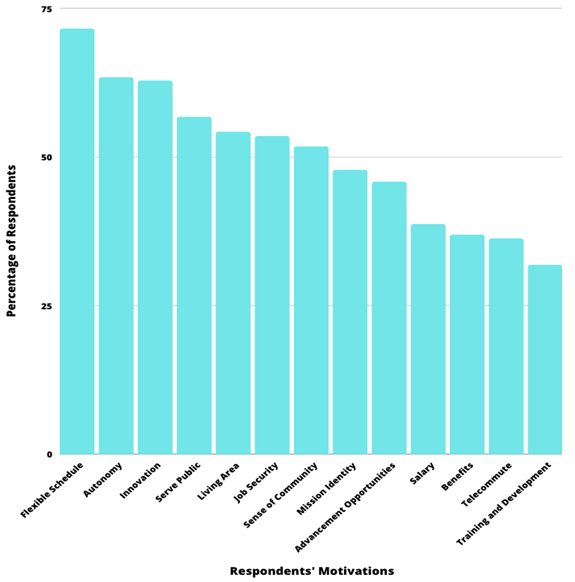

Our survey suggests that the driving elements of faculty motivation include the ability, freedom and space to do their work. When we asked faculty about what they value the most, focusing on elements they characterized as “very” or “extremely influential,” the top motivators were:

- flexibility of work schedule (72 percent),

- autonomy or ability to provide input for decisions (63 percent),

- ability to innovate (62 percent), and

- commitment to serving the public (57 percent).

Careers in the private sector typically pay better than those in higher education, but the college or university environment provides opportunities that might not be found elsewhere. Faculty members value working conditions that allow them to do their jobs and place a far lower value on motivators related to pay and benefits.

Not only are faculty being challenged to remain in higher education with lower salaries than they might receive in other sectors, but the climate of academic freedom that faculty enjoy is being challenged. Florida has limited the ability of faculty to discuss race and equity in the classroom. Several states have attempted to remove or limit tenure to control what faculty teach and research. University faculty have chosen careers that provide autonomy, but the rise in anti-education policies around the United States threatens the loss of faculty to outside professions.

Graph 2: Top Motivators (“Very” or “Extremely” Influential)

Courtesy of Sean McCandless, Bruce McDonald and Sara Rinfret.

Lesson No. 3: There Are Solutions

Despite the fact that some of the challenges, such as those surrounding salary levels and attacks on tenure and academic freedom, are difficult to address, our data nevertheless offer solutions, helping us walk back from the cliff. We captured some of these solutions in the voices of faculty who completed our survey.

- Financial security and emotional well-being: “I wish my university would [conduct a study on] the number of faculty who are housing and food insecure or study faculty mental health—both are problems on my campus mostly due to the low pay. In my group of colleagues, not all in my department or field of study, the majority of us have side gigs to earn extra money to make ends meet, and we’re full-time with tenure.”

- Opt-out policies: “Make policies (such as paternity leave) opt-out instead of opt-in policies. This would remove some of the stigma some faculty still feel about taking advantage of these types of work-life balance policies.”

- Career pathways: “There is also a need to provide appropriate mentoring/coaching for career development at my level—it’s no use if people are assigned to mentors who are uninterested, don’t take it seriously, are too busy with their own plans. Offer a career pathway that is properly supported through development opportunities.”

“[Be] better at tapping qualified faculty for leadership, rather than only those who have ambition.” - Skills development: “Offer training[s] on specific skills such as media training, managing digital identity, etc. that are not directly related to careers but that still help me do my job.”

- Career tracks: “The biggest issue for me is the current workload. I think it would be useful if there were career tracks differentiating between people focusing more on research and people focusing more on teaching. Currently, everyone is supposed to do everything, which is not efficient.”

- Address divisiveness: “There are real divisions between levels of faculty. The tenured faculty do not treat others as peers. The perception about administration and faculty isn’t healthy, either.”

Our goal as educators is to understand the nuances of the workforce so that we can prepare students to enter it. The environment in which higher education operates has changed significantly in recent years, often leaving faculty stressed, burned out and considering leaving the academy. We cannot forget that an educated populace is essential for a vibrant democracy. Higher education is one access point to inform the citizenry, and we need to ensure we do not lose sight of the well-being of our employees.