You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Tom Werner/Getty Images

I recently returned from an academic conference. It was the first I’ve attended since the start of the pandemic and my first since becoming chair of a small humanities department at a big Midwestern university. It was a welcome return to all the usual pleasures and even the petty annoyances of academic meetings.

What was different this year was the existential angst that sooner or later surfaced in every conversation. “West Virginia,” “enrollment cliff,” “program cuts”—these phrases were uttered in whispers, as if speaking them aloud might rain an academic plague on one’s own home institution.

I’ve never felt such a pervasive and shared sense that we are living through extraordinary times and that the landscape of higher education is undergoing seismic shifts.

To maintain my sanity, I toggle between two very different spaces in my brain: imagining alternate careers I might pursue (historian for hire creating coffee-table vanity family history books for the one percent?) and imagining strategies to restore the liberal arts to a state of flourishing.

Liberal Arts on Life Support

There is widespread agreement on the clinical presentation of illness that has drained students from liberal arts classrooms, an illness precipitated by the skyrocketing costs of a college education leading students and their families to prioritize a “useful” degree and, in just the last few years, the plummeting faith in higher education among Republicans. The number of history majors has declined by more than 30 percent in under a decade.

There is less agreement on what such numbers mean and even less on what should be done in response. There is, however, a troubling—and deeply flawed—prescription being issued by educational consulting firms. Provosts and presidents are counseled to invest in growth markets and pull back from “legacy” disciplines that seemingly don’t contribute to economic growth or arm students with “workforce readiness.” This narrative drove the cuts at the University of Maine at Farmington, West Virginia University and elsewhere, and it is driving discussion of possible program cuts at Miami University in Ohio and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

This narrative rests on an analogy of student course selection operating in an unregulated market where declining demand should trigger decreases in production. The logic is appealing: there are no bad guys, only the operations of the invisible hand. Humanities faculty members are today’s buggy makers: obsolete.

The logic is also faulty. Student course selection has never existed in a frictionless market. As long as there have been universities, there have been required courses of study. A student at Harvard in the 17th century followed a prescribed curriculum. As a college student at a small liberal arts college in the late 1980s, I followed a curriculum of distribution requirements ensuring I had, in addition to my major in religious studies, a healthy smattering of math and science courses and four years of instruction in a foreign language, as well as physical education and a swim test. These 17th- and 20th-century requirements reflected institutional and broader societal norms and values about what it means to be a college-educated person.

Nutritional Deficits

But the landscape has changed drastically in recent decades. At the same time the number of majors in fields like history and languages has been declining nationally, a related issue is that many students are opting out of introductory courses in humanities disciplines. This is not because students once loved history and no longer do. Rather, it reflects the meteoric rise of Advanced Placement and dual-enrollment programs, which have taken a sizable bite out of what have long been the bread-and-butter courses of history departments.

The goal of enabling students to graduate with less debt is admirable, but the means are flawed. We are essentially saying that if students can demonstrate they have eaten enough peas while in high school, they are exempt from eating any vegetables in college. They may make their way through college more quickly (this point is debatable), but they will not be as educationally well nourished as their peers who consumed a more balanced diet throughout their college careers.

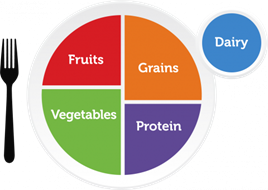

Distribution requirements circa 1985 generally ensured that students consumed the curricular equivalent of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s MyPlate.

Image courtesy of myplate.gov.

At my institution, it is fully possible that a STEM major will not take a humanities course until their third or fourth year. And it is even possible that they reach commencement never having been physically in the same room as a humanities professor, as we see more STEM students opting for online asynchronous options to fulfill their general education requirements. Combine this with the cultural cachet (and funding streams) of STEM, and the humanities are operating at a significant disadvantage.

Humanities Deficiency Syndrome

The result is our graduates are often malnourished, despite having ticked all the required boxes. What they lack is the essential activator nutrient provided by the humanities, which is best delivered in small, face-to-face learning settings.

This is not to deflect responsibility from our own house. The way we offer humanities courses today has changed little in recent decades despite the seismic shifts in the landscape of higher education. In the era of dual enrollment and online instruction, the distribution requirement model (i.e., the balanced plate model) can no longer ensure that students gain what they need to properly synthesize their learning across the disciplines for maximum educational benefit.

A premedical student in my intro-level course on American religion, which now usually runs online, will hopefully gain important historical and cultural content and critical thinking skills, but I believe that without a prior, targeted introduction to the humanities, they will likely fail to make important connections to their chosen path of study.

Co-Labs: A Case for the Integrated Humanities

Students would benefit from more targeted curricular offerings that would increase the “bioavailability” of humanities nutrients. I have been working to build support on my campus for what I am calling co-labs: one-credit humanities courses attached to high-enrollment STEM courses that would provide exactly this kind of synergy.

This low-cost solution responds to the current challenges and context of higher education while also addressing the needs of today’s students to gain critical humanities skills essential to their STEM careers.

Let’s say a Biology 101 course enrolls 400 students. The professor lectures. Graduate assistants oversee the labs. And humanities professors offer a wide array of co-labs (20 to 25 sections of 15 to 20 students per co-lab) for students to choose from. In my co-lab, I would teach botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, which invites students to think about the interplay of culture and scientific research as well as issues of sustainability, epistemology, history and religion.

The possibilities would be endless: a colleague in history who focuses on race and the history of medicine might teach a co-lab based on Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. These could be weekly meetings for an hour, or they could be intensive experiences over two weekend afternoons. A geography professor might bring students out to work and learn at the site of an urban farm that provides fresh vegetables to residents living in food deserts. The model could work equally well in many STEM fields: a computer science course might offer a co-lab focused on algorithmic biases in which students read Safiya Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression or texts on the ethics of AI.

All these experiences would provide a pointed introduction to the inescapably human contexts in which all STEM research and careers operate.

This model requires very little in the way of capital investment. The resources are already available in the form of underutilized faculty: what’s needed is institutional will to create the bureaucratic structures.

Co-Labs for Community

Additionally, co-labs could be a key mechanism to make real progress on university mission statements regarding student retention as well as diversity, equity and inclusion by providing new students in large lecture courses the chance to connect in small groups, with an experienced humanities professor around a topic of mutual interest. In this way, co-labs would also help STEM departments further their DEI goals, something they might struggle to do within the traditional parameters of Biology 101.

If we don’t find a new mechanism to integrate the humanities, who will translate complex scientific research for a general audience? How will medical professionals learn to empathize and communicate with their diverse patient populations? How will tech innovators learn to consider the ethical implications of their creations?

The humanities are not a luxury in a STEM-driven world. They are a necessity.