You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

yalcinadali/iStock/Getty Images Plus

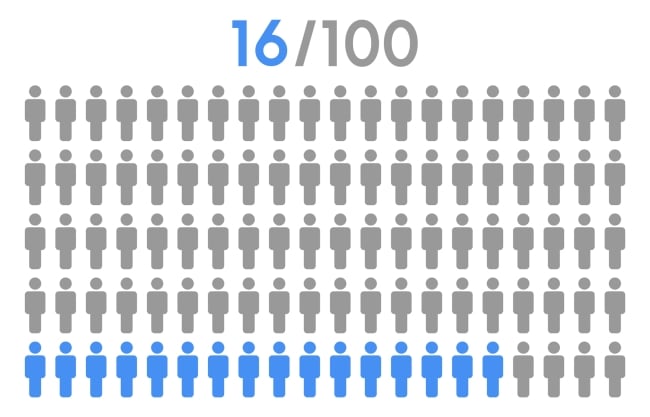

We recently returned from the annual meeting of the National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students (NISTS), an organization exclusively focused on the needs of transfer students, especially those who wish to move from a community college to a four-year institution to earn a bachelor’s degree. As longtime attendees, we were inspired to once again be in the company of hundreds of other transfer advocates, gathered to share practical strategies and best practices for supporting student transfer and success. But we cannot stop thinking about one sobering statistic discussed during the meeting’s opening session that shadows all our hard work: 16 percent.

That figure comes from new research jointly released by the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University; the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program; and the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Dishearteningly, their new research shows that while nearly 80 percent of first-time community college students have the laudable ambition of completing a bachelor’s degree, only 16 percent manage to do so within six years. The percentages are even lower for more vulnerable students, including low-income, Black, Hispanic and older students.

Sixteen percent. This figure hasn’t moved much since the data was first collected; an earlier report from 2016, tracking community college students who first enrolled in 2007, found a bachelor’s degree completion rate of 14 percent. In short, despite years of dedicated work, we haven’t moved the dial on transfer student success.

As lifelong transfer champions, this outcome is a punch to the gut. But it’s even more tragic for the large numbers of students left behind with a trifecta of terrible: some college, no degree that might translate into a family-sustaining wage and student loan debt. In the U.S., we now have 40.4 million former students with some college and no degree.

In recent decades, education professionals and policymakers have raised the visibility of transfer; implemented new laws and policies to streamline the transfer process; supported more advising to help students navigate this complex transition; and advocated for transfer-specific orientation programs, transfer student centers and on-campus housing for transfer students. Organizations such as NISTS have regularly shared information about programs that serve transfer students effectively and have advocated relentlessly for their fair treatment in undergraduate education. Nationally, at least 36 states have implemented statewide transfer policies designed to streamline the process for students and to ensure, to the extent possible, that their courses will transfer for full credit.

Still, the brutal fact is that not even two in 10 students who start at a community college earn a bachelor’s degree.

How did we get here?

Some big picture takeaways have emerged. First, transfer between two- and four-year institutions is—to state the obvious—complex, but the evidence suggests that there is no collective desire to simplify the system. As students attempt to navigate the transfer transom, they swim in a college ecosystem of nearly 4,000 institutions. All of those institutions treat the transfer process differently, whether that be through a unique set of admissions requirements, nuanced credit acceptance practices or specific enrollment prerequisites. This inherent complexity results in a transfer pathway that is murky, unclear and confusing for students, especially our most vulnerable ones who have little or no “college knowledge.” While we celebrate the independence of a highly diffuse educational marketplace that meets the needs of different students, this institutional diversity also creates enormous headaches for students switching from one institution to another, frequently resulting in lost credit, “transfer shock,” and low degree-completion rates.

Second, as a nation, we have yet to understand that credit mobility— the ability of students to port their college credit from one institution to another—is an equity issue. As things stand, our nation’s most disadvantaged students are the ones most likely to lose their credits along their academic trajectories. Recent research has shown that only 58 percent of transfer students were able to transfer 90 percent or more of their community college credits, with more than one in 10 losing nearly all their credits. This lack of credit mobility means that these students are much less likely to ever graduate with the degree they sought to earn. (While we’re at it, finding a way to award working adults academic credit for their workplace-based learning is essential. Institutions have no problem awarding academic credit for the internships of traditional-age students. Equity demands that we find a way to do the same for working Americans.)

Short of dismantling everything, what are our next steps? Some argue that the last two decades of work set the stage for increased future transfer rates. Perhaps. Certainly, things like common course numbering and block-credit General Education plans have reduced complexity for students. Others will argue that more substantive innovations—such as guided pathways and the widespread reform of remedial courses in community colleges—have not yet had time to play out. In time, those innovations will build momentum toward a more robust transfer pathway.

Our view is that this work must embrace more comprehensive reform that is linked to broader transformative changes in all of U.S. higher education. However important it is to maintain current efforts—transfer orientations, more advising, better articulation agreements, creation of transfer-affirming campus environments—the data shows that such efforts appear unlikely to significantly improve the outcomes for the number of transfer students we need to serve. Instead, we must integrate those efforts within a broader network of national initiatives that are likely to boost completion rates for all students.

What are those initiatives? A return to the “basics.” For decades, this nation has spent billions creating extraordinary access to college for students from our most vulnerable groups. Now that we have largely achieved access via the world’s greatest amalgam of open-access community colleges, we must provide the wrap-around life supports to help students maintain momentum toward the bachelor’s degree.

Currently, life supports for our students are insufficient. At least 8 percent of undergraduate students experienced homelessness in the past month. Another 22.6 percent report being food insecure. More than 22 percent of students are parenting and frequently lack affordable childcare. At least 16 percent lack reliable internet access, a commodity we learned during the pandemic is essential to college-going. To significantly improve degree attainment, we need to address these more fundamental issues, many of which are represented in a series of initiatives from the ECMC Foundation, where Stephen serves as strategy director for postsecondary education transformation. When we facilitate degree attainment for our most vulnerable students, we improve the educational pathway for all our nation’s students.

Transfer advocates will argue that community college students seeking the baccalaureate degree need special attention. We agree. The special challenge for students changing institutions in the middle of their undergraduate career is not to be dismissed. In California, the two- to four-year transfer pathway has been a central tenet of that state’s Master Plan for higher education for the past six decades. Moreover, transfer between and among institutions is now a fact of postsecondary life for a majority of all undergraduates. CCRC data further shows that only 8 percent of all bachelor’s degree completers who started at a community college follow the traditional 2 + 2 vertical transfer pathway; the center reports that “2 + 3, 3 + 3, and 2 + 4 patterns were slightly more common, though no one pattern applied to a majority of transfer students.” Additionally, “one in five students ‘stopped out’ for a year or more, re-enrolled, and subsequently completed a bachelor’s.” Even a well-designed transfer center will struggle to meet the needs of students in all these different circumstances.

There is nothing good about a success rate of 16 percent. We must address the needs and circumstances of all of our nation’s students, regardless of the number or types of institutions they have attended. Can we do better? We must.