You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

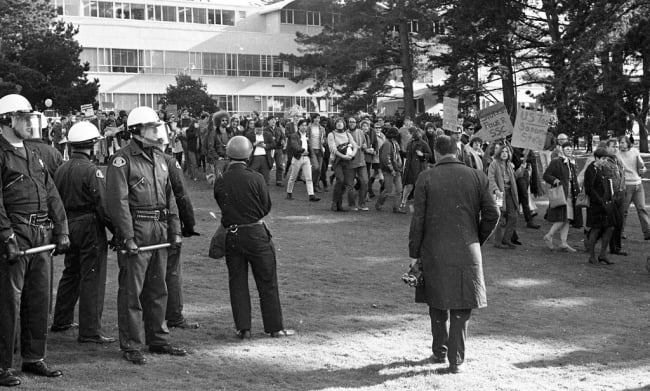

Will Clark draws on San Francisco State’s history of activism, including the 1968 strike, to advise today’s faculty about how they should stand up for a democratic form of academic freedom.

Right now, fear is taking hold over the threats universities will face from a hostile Trump administration. We’re advised to relinquish diversity as a framework, dismantle recently built DEI infrastructure or emphasize thinking with the enemy. Such postures take the shibboleths attributed to university liberalism and shrink their presence. They capitulate to a right-wing political movement intent on remaking the university in a regressive image. We need not look further than universities in Florida and Indiana to see our future.

But in the coming crisis, our work cannot just be defensive. Rather, our future lies in collective action—in work modeled by an academic unionism currently thriving in graduate education but eschewed by elite faculty ranks—that will allow universities not just to survive but to thrive as collectives of labor and scholarship after decades of neoliberal austerity.

In constructing a different academy through crisis, we must begin organizing now around two intertwined professional and institutional frameworks. These frameworks are academic freedom and the democratic deliberation offered by shared governance. They are ready-made vessels from which our broader organizing can build.

First, our jobs depend on preserving academic freedom not as an individual faculty practice, but as the collective responsibility it has always been as a disciplined mode of knowledge production. Second, as officers of our institutions, we have obligations to ensure that our institutions prioritize education that comes from the knowledge we produce collectively, not from political or state mandates.

These areas are not new: As the American Association of University Professors has argued, commitment to academic freedom defines our jobs but also flows through the democratic and deliberative infrastructure of shared governance. Together, these offer us critical areas of mobilization for protecting students, departments, campuses and professional rights.

At my campus, San Francisco State University, a draft policy introduced to the Academic Senate last fall is instructive. This draft policy would remove previous language that committed “to [upholding] and protecting the principles of academic freedom responsibility, which both reflect and enable the university’s core mission and values.” Instead, the draft policy emphasizes our need to adopt a position of institutional “neutrality.” The revision conceptualizes academic freedom as an individual, not a collective right, and asserts that the university itself “cannot reach a collective position” without inhibiting disagreement, a shockingly antidemocratic claim.

Many faculty saw the rise of neutrality as a misprision, responding to a moral panic about cancel culture and threats to individual faculty, rather than to the rapidly expanding panoply of legislative, political and donor-based infringements on academic knowledge that define our present. In response, some of us organized to assert that academic freedom requires active, democratic deliberation as an already defining aspect of our profession. We drew from our union’s collective bargaining agreement, which argues that the “concept of academic freedom is accompanied by a corresponding concept of responsibility to the university and its students.”

Our union’s framework rejects a view of academic freedom reduced merely to the rights of individual academics to teach and pursue research without censorship. Similarly, Robert Post, Joan Wallach Scott and others argue that academia’s balance of disciplinary self-regulation, committee contribution and public comment requires ongoing collaboration. Our procedures extend not from the individual but a network of arbiters who have a shared role in interrogating, mediating and validating knowledge. This collective approach does not square with the deregulatory, individuated, market-driven and ultimately neoliberal Chicago Principles, wherein the university professes individual academic rights but in reality merely shields itself from liability.

Building from the infrastructure of our disciplines, we must see academic freedoms as structurally related to our institutional obligations, especially shared governance. As contributors to The Chronicle of Higher Education and Inside Higher Ed agree, adopting neutrality abdicates responsibilities to our campuses, when what is needed is democratic and disciplinarily engaged deliberation among faculty, students and staff that is contextual to our communities. This means fostering deliberative spaces and policies that acknowledge our obligation to speak from our disciplines, rather than merely to invoke academic freedom as a passive, individual right.

More significantly, an emphasis on the university as a collective space counters the already-emerging charge that identity politics is the true culprit of the backlash we face. In fact, the university has been a space in which diverse knowledges and the economics of labor coincide as sites of struggle that we have yet to mobilize. Again, San Francisco State is instructive. Our mission to seek out social justice, born of the campus strike of 1968, gave birth to the nation’s first College of Ethnic Studies. Social justice and ethnic studies are not neutral, yet they embody our core mission. Extending both has required ongoing struggle, and the kinds of collective action that have defined our campus community as a one of justice and labor activism. If colleges have been defeated, the blame lies with a neoliberal model that individuates identity, labor and minoritization. Rather, the connection of labor with all forms of minoritization offers a response our campuses can use as a model in the political struggles to come.

Even before the election, faculty have been censored and fired for speech undesired by legislators, donors or other actors. Union organizing, critical race theory, LGBTQ studies and Palestine are just some of the bogeymen justifying punishment. In many instances, the speech of those targeted extends from disciplinary practices that academic freedom nominally protects. Without coupling academic freedoms to our democratic role in governance and our collective responsibilities as academic workers with rights, targeted silencing will expand.

By reframing academic freedom as a shared obligation rather than an individual right, one that we can activate and secure through our existing institutional roles as workers with powers of shared governance, we achieve a more vital end: organizing together as faculty, staff and students, despite our inevitable disagreements. Moreover, we can connect our struggle to the economic needs, knowledges and speech rights of other workers. The possible coalitions expand, mirroring those we must build nationally across groups whose shared interests have been splintered by corporate austerity.

This is a role that administrations cannot foster in the defensive posture they are already adopting. Rather than responding with fear or deference, it is paramount that we work together, across our departments, disciplines, class statuses and academic bodies to defend our collective rights to knowledge production and teaching. Only then can we realize the possibility of the institutions through which we work as a bulwark against the repression to come.