You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

filo/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

On Nov. 21, trustees of California State University, the largest and most diverse public university system in the United States (more than 461,000 students and 63,000 faculty and staff), heard an update on what Hayley Schwartzkopf, the associate vice chancellor for civil rights programming and services, called “a new vision” for addressing unprofessional conduct: “Other Conduct of Concern” (OCC). This “vision” threatens to turn the CSU into an Orwellian dystopia.

Here’s the backstory: In 2022, the story broke that the system chancellor at the time, Joseph Castro, allegedly mishandled sexual harassment complaints against a senior administrator when he was president of California State University, Fresno. To calm the resulting scandal, CSU hired the Cozen O’Connor Institutional Response Group to conduct a full assessment of the system’s Title IX and Discrimination, Harassment and Retaliation (DHR) programs.

The Cozen group delivered its report in July 2023. Over all, the report found “the infrastructure for effective Title IX and DHR implementation” to be “insufficient” and laid out a series of recommendations for improving those processes, expanding education and prevention programming, and confronting the massive trust gap between the administration and everyone else. All that is to the good.

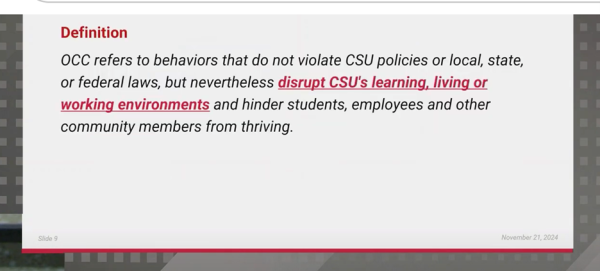

But the Cozen report added something new, something that goes well beyond Title IX and discrimination: a category called “Other Conduct of Concern.” I had not heard this strange phrase before: it seems, best I can tell from Google searches, that the Cozen team invented it. In the Nov. 21 presentation to the trustees, Sarah Fried-Gintis, CSU’s senior systemwide director for academic and staff human resources, defined the term thus:

“Behaviors that do not violate CSU policies or local, state or federal laws, but nevertheless disrupt CSU’s learning, living or working environments and hinder students, employees and other community members from thriving.”

Crucially, “OCC” does not require an actual violation of university policies or laws. Instead, the bar is lowered to include anything that might “disrupt CSU’s learning, living or working environments” or prevent anyone “from thriving.”

In other words, behaviors or speech that before did not rise to the level of an infraction requiring discipline now are a form of misconduct. In her presentation, Fried-Gintis said that “misconduct at the CSU is now conceptualized as falling into one of three categories: conduct that violates CSU’s nondiscrimination policy, conduct that violates any other policy and other conduct of concern.”

Screenshot, courtesy of Peter C. Herman

A draft guidance pamphlet distributed by CSU’s systemwide Human Resources office states that OCC will be addressed differently depending “on the nature of the behavior(s),” with potential outcomes including “education, counseling, coaching, mentoring, training and restorative processes.”

The document gives the following examples of behaviors that qualify as “Other Conduct of Concern”:

- “Verbal abuse”

- “Intimidating behavior”

- “Microaggressions that are not persistent, pervasive or severe”

- “Bullying”

- “Hostile language”

- “Acts of bias, intolerance or harassment that do not violate CSU’s Nondiscrimination Policy”

Almost everything on this list is either already prohibited by policy or law or, as the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression says in a Dec. 30 letter to the CSU trustees, hopelessly subjective. But it’s with the third item, “microaggressions that are not persistent, pervasive or severe,” that “OCC” descends into Orwellian territory.

A microaggression is all about impact, not intent. It does not matter if the person accused of microaggressing meant to insult the victim, or if the person had any idea that the victim might be offended. Intent—the crucial component in defining a crime in Anglo-American law—is irrelevant. This means that the accusation alone constitutes guilt. If someone says you have committed a microaggression, then you have committed a microaggression.

I am not exaggerating. San Diego State University’s draft rules for dealing with “OCC” refer to an “impacted/affected party,” on the one hand, and an “offender,” on the other. Both parties are encouraged to undergo a “restorative practice” (such as a “restorative circle, restorative conference, facilitated dialogue, conflict coaching, etc.”) and the point is to explore “ways the offender can repair the harm they have caused.” If the “offender” refuses to participate in a “restorative practice”—technically their right, but a difficult one to exercise when requested to participate by one’s superiors, such as one’s department chair or dean—administrators are to “make an effort to engage in restorative questioning with the offender.” Not “the accused,” but “the offender.” There is no presumption of innocence.

Lowering the bar even further, the microaggression in question does not have to be “persistent, pervasive or severe.” Make one slip, or be perceived as making one slip, and you are subject to a pseudo-disciplinary and “restorative” process.

Finally, and with this the bar disappears altogether: The system’s draft guidance suggests that “individuals who experience or witness OCC” (italics my own) are encouraged to report it. The complainant does not have to be the target. Any third party can report “OCC.” Someone overhearing a perfectly normal conversation between two people, neither having any problem with the interaction, can denounce one or the other to the university’s authorities.

Nor will the First Amendment or academic freedom necessarily protect you if that happens. Fried-Gintis stated in her presentation to trustees that “OCC” “will not jeopardize … academic freedom and the rights of all to freedom of speech and expression.” But the draft guidance pamphlet suggests otherwise.

To the question: “Is the behavior(s) protected by principles of free speech or academic freedom?” the answer is not “the investigation stops because the speech is protected.” Instead, the matter gets bumped up to a higher authority: “If yes, consult with General Counsel before taking next steps.”

Why would the CSU adopt this nightmare of a policy? The answer partly lies in what Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt call “safetyism”:

“A culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. ‘Safety’ trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger.”

“OCC” is safetyism on steroids. The draft policy assumes that everyone on the campus, be they administrators, faculty, staff, students or visitors, must be protected from any speech or behavior that they (or someone else) find objectionable because it might hinder their ability to “thrive.” Leaving alone the slipperiness of defining “thrive,” “OCC” will likely have the opposite effect. To draw from Lukianoff and Haidt, by trying to keep everyone “emotionally safe” by protecting them “from every imaginable” slight, the administration sets up a negative feedback loop: Everyone becomes “more fragile and less resilient,” signaling to the administration that everyone needs yet more protection, which makes everyone yet more fragile, less resilient and more prone to see themselves as victims.

Equally bad, “OCC” puts everyone under surveillance, destroying any and all trust between students, faculty, staff and even administrators. Every interaction inside and outside the classroom becomes fraught with danger since you can be denounced at any time by anyone.

In 1984, Winston Smith observed that “You had to live—did live, from habit that became instinct—in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.” Orwell perfectly describes what “OCC” will do to the atmosphere on CSU campuses. Instead of a spirit of free inquiry, instead of a clash of opposing ideas, everyone will self-censor for fear of giving offense, because the slightest mistake (remember, the offense does not have to be “persistent, pervasive or severe”) could result in your being denounced and deemed an “offender.”

Not only is “OCC” a disaster on its own terms, it’s also politically foolish. The Trump administration has clearly indicated that higher education is a high-value target for retribution. In 2021, Vice President JD Vance called universities “the enemy” and called for “aggressively” attacking them. In July, President Trump released a video in which he announced his plan for creating a new set of accreditors dedicated to “protecting free speech,” among other goals. Obviously, “OCC” doesn’t just chill free speech: The policy puts it into a deep freeze.

So you have to ask: Why would the CSU’s Trustees rush to implement a policy guaranteed to antagonize higher education’s enemies? Why would they so eagerly confirm the radical right’s worst stereotypes of academics? Why would they jeopardize the CSU by putting the system in the new administration’s crosshairs?

I have no answer to these questions.