You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

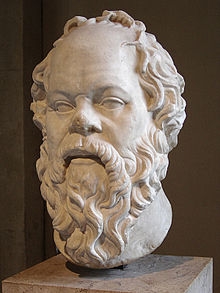

Socrates

Wikipedia

Socrates, the patron saint of liberal education, is not a patron saint of civic engagement. Although he claims to benefit Athens, he also admits to neglecting the duties -- from taking care of his family to concerning himself with politics -- that Athenians took to be conditions of good citizenship.

Nonetheless, colleges have long pursued both liberal education and civic engagement missions. And in the recent past, Cathy Davidson of Duke University and Eileen McCulloch-Lovell, president of Marlborough College, have called on liberal arts colleges and universities to tighten their embrace of civic engagement in order to prove their worth to a skeptical public.

Cathy Davidson’s two-year core “curriculum for real-world success” begins with Socrates and other great thinkers and ends in “an eye-opening year of entrepreneurial, service-oriented practical work.” McCulloch-Lovell calls on liberal arts colleges to cooperate on a Civic Scale, measuring, among other things, the extent to which alumni vote, “organize to make change,” and join “the Peace Corps or Teach for America” after college. According to McCulloch-Lovell, a liberal arts education that shapes citizens who score well on such a scale can claim to provide a return on public investment.

Civic engagement education and liberal education can support each other, but we have not thought enough about how they go together. To join them together well, we need to acknowledge the tension between liberal education and civic engagement suggested by the example of Socrates.

Socrates, rather than posing as a moral expert, reveals, as Plato has him say in the Apology, that we are “worth nothing with respect to wisdom,” that we do not know what we most need to know, especially how to lead a good and just life. As Dana Villa remarks in Socratic Citizenship, Socrates’ “energies are devoted to dissolving the crust of convention and the hubristic claim to moral expertise.”

Socrates’ activity is, of course, not entirely negative. Our longing to know, along with the pleasure of inquiring with friends into what is most important to us, may persuade us of the truth of Socrates’ best-known positive assertion, that the “unexamined life is not worth living for a human being.”

But “examine!” is an injunction that does not permit us to forget our ignorance. Insofar as liberal education claims, as it typically does, to be animated by the spirit of Socrates, it does not claim already to know the answer to the question, “How should one live?” This forbearance can set liberal education at odds with civic engagement education.

For civic engagement education can assume, as Davidson and McCulloch-Lovell do, that we already know what a good and just life is. McCulloch-Lovell presupposes that the scale by which we measure the success of our educational efforts “must include finding meaning in life in service to others and to the country.” Davidson’s civic engagement year focuses on areas with “radical income and health disparities” and on “organizations desperate for help in financially strapped times.” Both suggest that a meaningful life consists above all in service and good citizenship.

Yet a liberal education is compelled to take seriously, for example, Omar Khayyam’s argument that a life devoted to pleasure is more choiceworthy than a life devoted to social action, or Marx’s that revolution, not liberal citizenship, is our duty, or G.H. Hardy’s that greatness, not usefulness, should be our aim.

It must consider without prejudice the argument of some economists that taking the time to become informed about public affairs is irrational for most citizens, or of some political scientists that pursuing the popular aim of forming robust civil societies may harm rather than help some democracies. If we are devoted to liberal education, we cannot say in the first year, “How to live is a disputed question to which none of us knows the answer” and in the second, “Just kidding; we knew all along that you should ‘organize to make change.’ ”

But if liberal arts colleges do not teach students directly to be good citizens or to serve others, why should the public continue to subsidize them?

The defender of liberal education has two answers. First, the needs of an educational community devoted to inquiry overlap the needs of a democratic political community. In the course of articulating and testing their own views with the help of peers and of what Davidson calls “the wisdom of the ages,” students cultivate important virtues. These virtues, including the courage to state and subject to examination one’s deepest beliefs, and the self-restraint, civility, and sympathy required to deliberate with others, suit democratic politics, in which citizens must learn to struggle over fundamental differences without coming apart.

Second, civic engagement education benefits from being pursued in the context and spirit of liberal education. At a liberal arts college, curricular and co-curricular civic engagement work should draw students' attention to fundamental questions political or social actors ought to consider: What is a good society? What qualities of character are conducive to bringing such a society into being? How, if at all, does participating advance my own good? How, if at all, will my participation advance the common good?

While it is and should be conceivable that students who reflect seriously on such questions will opt out of civic engagement, a society that supports liberal education bets that the more common result will be reflective and intelligent participation in associational life.

Liberal education also has something to gain from civic engagement education, which strengthens the student’s sense of the connection between inquiry and practice. Pre-medical or pre-business curricula also connect inquiry and practice, but an education for civic engagement entails inquiry into the very kinds of contested questions about justice and the good life that are at the heart of liberal education.

Davidson and McCulloch-Lovell are right that it makes no sense for liberal arts colleges to turn up their noses at actual engagement in civic life. Programs like Project Pericles and the Bonner Program show that such engagement has the power to motivate students, hone their judgments, and, sometimes, transform them.

Educators, too, can only benefit from asking the kinds of questions about participation and the common good that their students will be asking when civic engagement and liberal education are effectively combined. Davidson and McCulloch-Lovell put forward a particular, contestable, vision of the good society.

McCulloch-Lovell is vocal about organizing to make change and volunteering with community organizations but silent about organizing to conserve traditions and volunteering for military service. Davidson is vocal about economic and social inequality but silent about individual liberties. She observes that acquaintance with Socrates and others can “help us deconstruct some of the cant of our era” but does not consider the possibility that civic engagement education in some of its manifestations is part of the cant of our era.

Keeping Socrates at the center of our civic engagement mission reminds professors, who are perhaps no less inclined than others to make hubristic claims to moral expertise, that we do not have the wisdom to settle the questions that divide democratic communities. It also prevents us from adopting too narrow an understanding of civic engagement.

Recent proponents of civic engagement are right that liberal arts colleges have to prove that they are worth the investment the public makes in them. Their argument that this worth should not be understood strictly in terms of winning higher salaries for students is a welcome intervention in the debate over the value of higher education.

But liberal societies need not insist, and have not of late insisted, that colleges directly teach the value of citizenship or engagement, any more than they need to insist or have of late insisted that colleges directly teach patriotism. Perhaps we sense the danger that if colleges take up the task of defining and proselytizing for citizenship they will become, because the meaning of citizenship is a matter of political dispute, new partisan battlegrounds, rather than safe havens for inquiry.

A different bargain between liberal arts colleges and the societies that support them is possible. As I have already suggested, liberal societies gamble that when students are given the freedom, leisure, and material to reflect deeply on the grounds of their actions, and when they develop the virtues cultivated in the course of such reflection, they will, for the most part, become more useful and intelligent citizens than they would have become had they been directly trained for citizenship.

Liberal arts colleges can contribute to the possibility that this gamble will succeed by offering students opportunities to pursue civic engagement, while setting that engagement on a firm liberal education footing. To be sure, by opening students to the possibility that the best life requires distance from society, liberal education may produce a handful of Socratic eccentrics. But if such eccentrics arise to challenge and harass their more numerous, more conventional, fellow citizens, so much the better.