You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

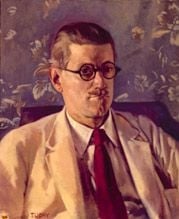

James Joyce in Paris

Wikimedia Commons

Departures are stressful affairs. In 1904, James Joyce, an Irish Modernist writer, and Nora Barnacle, his girlfriend, began their lifelong pilgrimage through Europe. They had just met, a few months before — she a hotel maid from Galway, he a Jesuit-educated young man with poor eyesight and an ambition to become a famous writer. Joyce didn’t deceive Nora when he predicted the discomfort of their upcoming elopement and their life in exile. He confessed that he could not “enter the social order except as a vagabond.” Propelled by the desire to encounter the new, they both left the familiar constrains of home behind.

And in the midst of the debate about the so-called crisis of the humanities, I want my entire academic field to draw inspiration from authors like Joyce. Without dismissing the very real financial crisis in humanities departments, I want to address another kind of crisis — not entirely unrelated to funding — the widely professed crisis of identity.

Can Joyce’s life and writing give us some direction to re-envision the humanities as a field? A sense of personal crisis and disillusionment compelled him and many other expat Modernists away from home. Joyce rejected formalized religion and the insular culture of turn-of-the-century Dublin. Yet he remained saturated with both religion and Dublin and explored them in his writing until he died.

Voluntary exile furnished him with inspiration and necessary distance from the familiar, a detachment that many creative writers consider invaluable in capturing the complexities of fictional settings. But Joyce wrote about his homeland with a great deal of warmth, not just criticism. In his fiction, he goes back to Dublin streets again and again, and he goes back to the West of Ireland, where his beloved Nora came from. The last paragraph of “The Dead” is the most touching description of a native land by a self-exiled writer.

James Joyce — a voluntary exile, a wanderer, a seeker — always came home. This master of experimental writing and irreverent violator of tradition returns home whenever he alludes to Odysseus’s wandering and whenever he lets us encounter his Irish equivalent of Odysseus, Leopold Bloom — an Irishman, a Jew, and a cuckold, an alienated character, an “ancient mariner.” As we plow through Ulysses, we read about Stephen Dedalus’s snot, Leopold Bloom’s erections and bowel movements, and Molly Bloom’s menstruation, and we’re not quite sure where we’re heading. Yet, in all this apparent directionlessness, we learn a great deal about suffering, betrayal, desire, and compassion. We know the characters intimately, and we want to reach out and touch them, cry with them, walk with them. We sympathize with Bloom, who responds to violence by proposing that the answer to “force, hatred, history, all that” is “Love.”

Exile and nomadism, those unsettling symptoms of Modernist physical and spiritual displacement, can furnish us with love — love for discovery, love for learning, love for the other. It is through leaving the comfort of home and encountering alien people and ideas that the humanities classroom thrives. We expect our students to enter the world of the unknown with courage, but we are often hesitant to do it ourselves. We should have the courage to face the new — collectively as a discipline.

Let’s look at the “crisis of the humanities” as an opportunity to re-envision the field, to send it off on a great adventure away from home. Let’s not treat the humanities as a field with a calcified identity, entrenched in the past. Lest you misunderstand me: This is not a call to forget about the past, to abandon Confucius and Aristotle, Beowulf and Dante, Voltaire and Tolstoy.

I want the humanities to remember home, but to be comfortable with change, to embrace new opportunities, to feel the excitement of letting their identity be molded by movement, not to be threatened by changing or porous boundaries. If we do not initiate new adventures and if we do not embrace an itinerant mode of exploration as potentially educational and formative, we will be forced to change anyway.

And the difference between choosing exile and being forced into a refugee status is profound. Joyce, for example, was never barred from returning to Dublin. He maintained his ties with Ireland and, if he chose to, he could always return home — through his experimental fiction and political essays or by visiting Ireland himself. Refugees facing real violence have no luxury of returning home.

Underfunded and disrespected humanities are the refugees of academe. In the last decade alone, whole departments have fallen victim to the corporate takeover of learning. So without dismissing the value of staying home, I want to suggest that we explore new ways of scholarship and that we travel to other disciplines — yes, including computer science and STEM — to enrich our thinking about our disciplines. Being homesick without being homeless, conversing with the past while imagining new beginnings — all this is potentially generative and exciting.

The writers we study in literature classrooms and the teachers who assign their texts put “home” in conversation with the tradition in order to other it. These writers often speak with each other across the boundaries of time and space. They leave home to drop in on distant relatives or total strangers. Colm Tóibín’s Testament of Mary responds to the New Testament and allows Mary to voice her dismay over the idol-worship surrounding her son and, eventually, her anguish over his death. Carol Ann Duffy revisits Greek and Roman mythologies to give voice to the women rendered mute by the original storytellers.

This is the essence of the humanities: embracing the nomadic state of not knowing and not belonging and, at the same time, living in the text and conversing with it freely; being rooted in tradition and challenging it; respecting the canon and revising it as we begin to understand who has been silenced; retaining our reverence for the printed book and letting ourselves feel excited about new modes of writing, publishing, and discussing literature.

Our disciplines are grounded in printed text or painted canvas, but they should also explore the new technologies that democratize people’s access to knowledge and allow the difficult conversation with tradition to happen instead of hiding behind a paywall. We should use these technologies with excitement and criticize them where they fail to deliver.

In the nomadic future of the humanities, scholars of sub-Saharan literature collaborate freely with visual artists and computer science experts on projects that would attract students and the general public. In the nomadic future of the humanities, business owners, nurses, and local artists join college students in poetry slams and book clubs. Our brilliant philosophers of gender, race, and class leave the campus regularly to engage middle-schoolers and high-schoolers in the life of the mind, leading discussions about the issues that affect them. In the nomadic future of the humanities, we prove that literature is not only for the elite few, that the beauty of the written and spoken word can move everyone, and everyone can try to articulate why.

To accomplish all this, the humanities will have to open up and venture out without the fear that we’re undermining some primeval principle of what it is we should be doing as scholars and teachers. Pretentious, intentionally obscure, and insular humanities will soon face decline. I do not dismiss the beauty and importance of navigating the world of ideas without any stated utilitarian purpose. But the humanities should be in flux, inviting others to join in their nomadism, open to other disciplines, learning from them and teaching them, too.

Like James Joyce and other Modernists who left home in both literal and metaphorical ways when they abandoned the comfort of established modalities of expression, the humanities — as well as their teachers and students — should be encouraged to redefine themselves as they cross borders and encounter alien worlds. If the humanities could repeat Stephen Dedalus’s call “Away! Away!,” with equal enthusiasm but with less arrogance, perhaps we wouldn’t be talking about their “crisis.”

If we acknowledge the importance of the formative origins of the field and continue exploring them unapologetically and with passion but in a way that would be inclusive of those unfamiliar with the prohibitive jargon of most academic papers, we could capture the interest in ancient philosophy, Medieval morality plays, or postmodern theater among people who are not affiliated with academe but who enjoy the life of the mind. We could avoid the charge of being locked up in the Ivory Tower, waiting for our slow death as the masses outside rage against us. If we admit that revamping and energizing the field will take resources, creativity, and courage, and if we reward the courage to leave “home” in search of discovery, the humanities classrooms will again be filled with students.

We’re already doing a lot of great work on campuses across the nations: tweeting about philosophy, transforming theories of public engagement into practice in local communities, or sending students to professional conferences, writers’ workshops, and exhibitions. But it would take a more systemic shift to make all this possible on a larger scale.

First, a lot of these creative ways of approaching the humanities are time-consuming and costly, and grants for the humanities scholars and teachers, always unimpressive, are becoming even more rare as the National Endowment for the Humanities and Fulbright funds are being drastically cut. Second, we should start rewarding public engagement with the humanities in tangible ways. A series of compelling and clear blogs about an obscure 17th-century poet should count toward tenure and promotion, together with required well-researched papers published in specialized, peer-reviewed journals. Both forms of engagement with our subjects are important and valid, and they should be complementary as well as rewarded.

Publishing in traditional academic journals tests new ideas on the forum of narrowly specialized scholars and adds new knowledge to the field. Explaining our research to the general public in clear, accessible prose could make it possible for us to continue testing new ideas in a narrowly specialized forum. If popularizing the humanities, the hard work of bringing them out in the open, is derided as a job of a traveling salesman, the humanities will lose public support, and along with it, the resources necessary to thrive.

So let us together see the humanities take a stroll into uncharted territories but always remember home, like Leopold Bloom who — after walking through Dublin for many hours — returns in a chapter called “Ithaca” to his unfaithful wife’s bed and kisses “the plump mellow yellow smellow melons of her rump.” Voluntary exile from Ithaca, from the Blooms’ jingling bed, from Ireland, from Aristotle and Shakespeare, from a printed book and a lecture hall, will help us look at home upon our return in a new way, influenced by encountering the alien.

The humanities that boldly leave home — and yet always remember home—the humanities that are not afraid to take a risky detour, the humanities that are not too aloof to leave the campus and engage pressing issues with clarity and empathy — this is a field that will survive any crisis of confidence.