You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

State spending on public higher education has been in a free fall since the Great Recession. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in 2013-14, average state support for higher education was 23 percent less than it was prior to the recession. For many colleges and universities, reductions in state spending have left sizable budgetary holes that cannot be filled exclusively with spending cuts.

The result, in most cases, has been steady increases in tuition and fees charged to students. In effect, as public investment in higher education has declined, the cost burden associated with public higher education has increasingly shifted to students and their families.

Public concern, if not outcry, over this situation has resounded nationwide, and presidential candidates from both political parties have taken stands that higher education has become unaffordable for many students and families. Their response has been to propose policies that would lower the price of college as well as build a stronger federal-state partnership to ensure that states make appropriate investments in higher education.

However, missing from this conversation is the question of how investments -- and cuts -- are distributed among institutions of higher education. While state support flows to all public colleges and universities, some institutions depend on it far more than others. Research universities can look to endowment funds, gifts, auxiliary enterprises and federal funds for revenue when state funds decline, and their students are often more able to bear increases in tuition. But at community colleges and comprehensive public universities, state appropriations are the dominant source of funding, and when they decline, tuition must go up.

It is therefore important that policy makers move beyond the question of total dollars for higher education and consider where those dollars are spent. This issue -- which institutions get what funds -- is a common topic in K-12 education finance, but is often neglected in higher education.

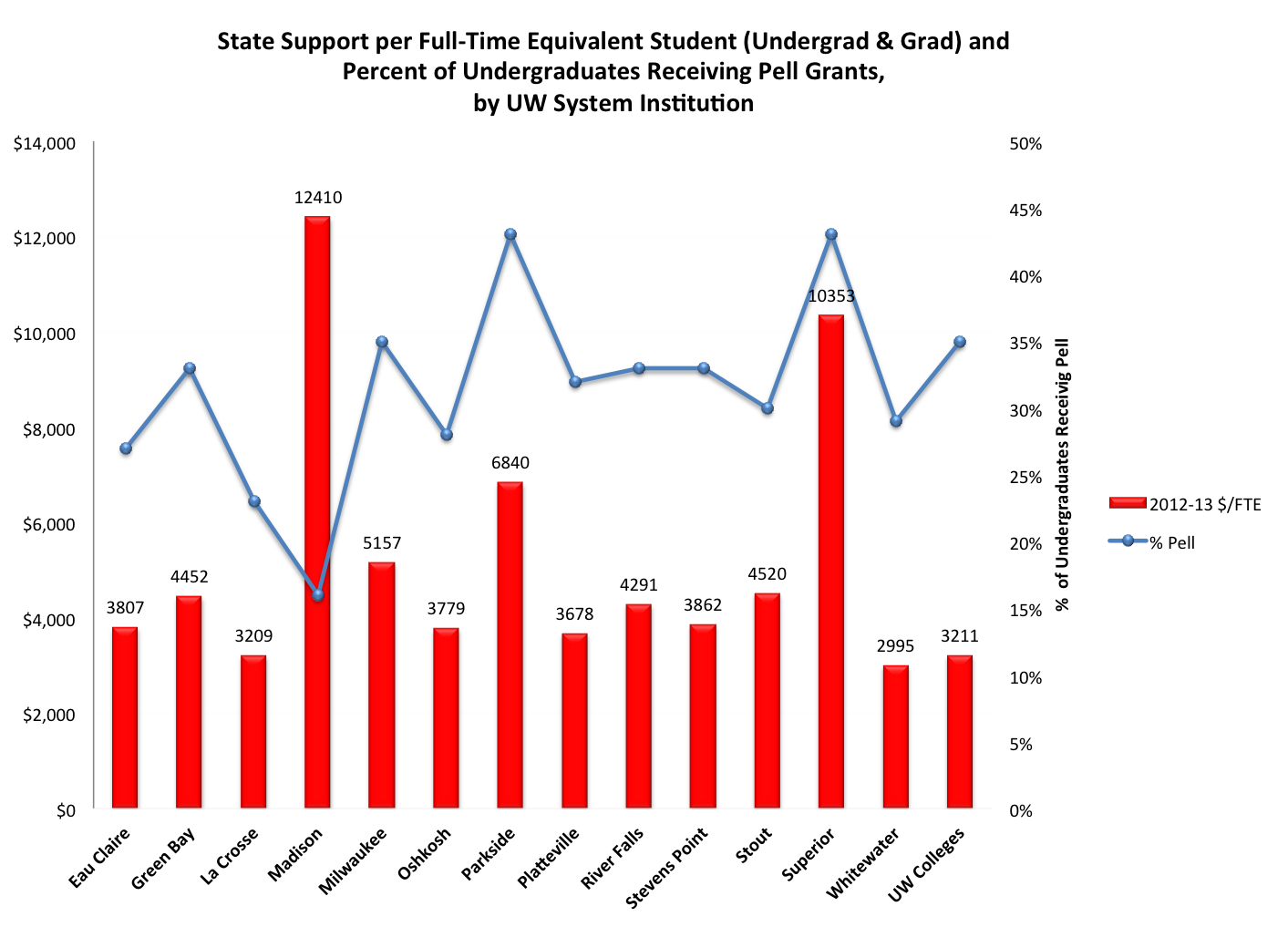

In July, the Wisconsin HOPE Lab (of which we are the director and an affiliate, respectively) convened a national meeting of experts to explore how state higher education funding is allocated. Given Governor Scott Walker’s recent budget and its corresponding cuts to the University of Wisconsin system, we spent time considering the per-student funding that the state of Wisconsin provides to its public colleges and universities. We noted that state spending differs significantly among institutions. For example, in 2012-13, the state provided the University of Wisconsin-Madison with approximately $12,410 per full-time-equivalent student (FTE), whereas it provided $5,157 per FTE to the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and just $3,211 per FTE to the two-year University of Wisconsin Colleges.

Differentiated state spending among higher education institutions is not new. On the one hand, legislators and college leaders argue these differences are appropriate and justified due to variations in the quantity and quality of education and related services offered students. And, frankly, that may be an important contributing factor.

On the other hand, the differences in the magnitude and distribution of Wisconsin’s expenditures among in-state higher education institutions raised red flags among the experts. First, while a case might be made that flagship institutions, like the University of Wisconsin-Madison, require additional funding over and above the statewide average to maintain its core functions, the opposite case could be made for institutions such as the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, which serves a greater share of first-time college students and students from less-advantaged academic background that, arguably, may require more intensive academic supports and services to complete college.

This idea of “vertical equity” is woven into the fabric of K-12 education finance and well articulated in school funding court cases nationwide. That is, state funding for elementary and secondary education is frequently distributed in ways that provide compensatory, or extra funding, above the norm for schools that serve concentrations of economically disadvantaged students. The research literature that examines nonschool factors influencing academic success has repeatedly reaffirmed the important role that economic advantage plays.

In an era where spending cuts have been the norm, applying such a standard to higher education raises serious questions not only about the extent to which all colleges and universities receive adequate funding to support their mission but also who is most impacted by cuts in state appropriations.

This question of who may be most affected by higher education cuts introduces another concern -- whether those cuts are fairly distributed. Another important observation made by our group is that institutions already operating at the margin have less capacity to buffer students and families from reductions in state funding. Consider the community college, long relied on to be the most accessible and affordable point of entry to education after high school. To fulfill that mission and keep tuition low, such colleges depend on state and local support. But over time, that support has eroded sharply.

The consequence of the rapid defunding of community colleges is staggering. Across the nation, between 2000 and 2012 it led to a doubling in tuition and fees -- from $1,842 to $2,696 in inflation-adjusted figures. Sometimes financial aid can help offset that cost, but it often cannot at community colleges, where aid budgets are thin. Thus, since 2000, out-of-pocket costs facing students in the lowest income quartile attending community college grew by 61 percent and students began taking loans at much higher rates and accumulating more debt that they have difficulty repaying.

Again, community colleges are less equipped than public universities to attract out-of-state students or raise tuition to offset cuts, and their spending on instruction and student services may be too little to begin with. The two-year University of Wisconsin Colleges serve more first-generation students, more part-time students and more adult undergraduates than any other institutions in the UW system. Does just $3,000 to $6,000 a year (the national average is $5,700) in state support adequately ensure that academically vulnerable, economically insecure students, working parents and nontraditional learners will receive a quality postsecondary education that will prepare them for the workforce and beyond? It seems highly unlikely.

Improving the sufficiency and fairness of state allocations for higher education will require shedding more light on within-state funding distributions. It also will also demand a more careful accounting of the real costs -- not just how much is spent -- associated with educating different groups of students at the postsecondary level. Such data are currently nearly impossible to come by, but they must be collected.

Are UW-Madison students truly more expensive to educate, and if so, why? Are there reasons that could help explain why students at UW Colleges receive the lower level of investment? It is long past time for these questions and others like them to be asked and answered. Absent an unexpected influx of new funds, the future of college affordability will depend on how state monies are spent. We need to start paying attention.