You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

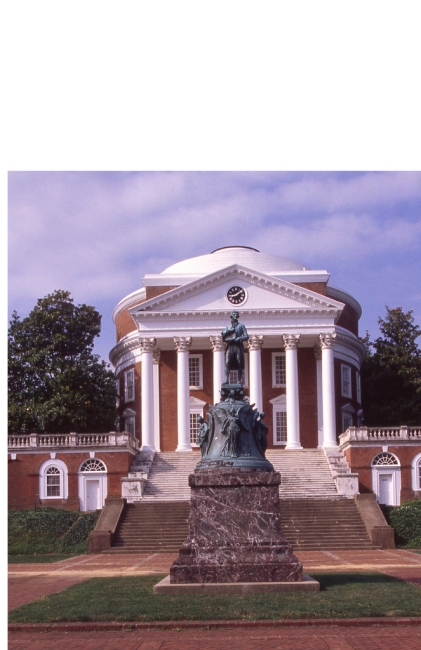

The University of Virginia

iStock

I went to Charlottesville, Va., with one aim: to be helpful. Despite my critique of President Teresa Sullivan’s raceless four-sentence response, University of Virginia administrators afforded me an important opportunity to address all faculty and staff members seven days after white nationalists devastated the campus with racist and anti-Semitic chants. This speech felt especially consequential; finding the appropriate balance of sympathy, support, challenge and inspiration was an enormous task.

I began by asking everyone in the auditorium to join me in a moment of silence for persons who lost their lives in the racial crisis. I prayed silently at the podium. Then I invited audience members to raise their hands if the white supremacy that was on display at the university the previous Friday horrified and disgusted them. Most, perhaps all, hands went up. “Well, do something about it,” I instructed the mostly white crowd.

I frequently use a video clip from a CNN study to help educators understand how young children are socialized in problematic ways to view people from other racial groups. The reason for showing it at UVA was to help faculty and staff members see how early the seeds of white supremacy are sown. I made the point that little (if anything) typically happens in K-12 classrooms to undo the racism that students have learned from their families and assorted forms of media when they were four and five years old, the age of children in the CNN clip. Most come from racially homogeneous residential contexts where they attended segregated high schools, I noted. Too many white students then matriculate to institutions of higher education thinking they are intellectually superior to people of color. Some enter college with disgustingly racist views like those white nationalists expressed in the 22-minute Vice News documentary filmed in Charlottesville. “White supremacists are not just the people unaffiliated with UVA who showed up with tiki torches a week ago,” I argued. “Many more work and attend school here.”

On several televised news programs last week, I heard whites characterize Charlottesville and its beloved university as inclusive. Blacks on those same shows had vastly different appraisals. This dissent along racial lines also played out via #ThisIsntUs on Twitter. I had dinner Thursday night at a Charlottesville restaurant that had a sign taped on its door that read, “We value diversity, equality and love in this establishment and in our community.” It seemed to me that people of color had a different view and set of experiences in the predominantly white college town.

Because it was my first visit there, I could not speak with certainty about this. I therefore shared a handful of findings from my racial climate studies conducted on campuses demographically similar to UVA. I asked audience members to juxtapose the manifestations of white supremacy described in my data with racial trends at their institution. I did not detect disagreement. In fact, there were several affirmative head nods. “So then, do only certain displays of white supremacy horrify you?” I asked.

Too little is taught and learned about race on college campuses. It is entirely possible for students to come to UVA with racist views that are never engaged, contested or revised. They then go on to assume positions of significant authority after college. Given that whites are the single largest racial group that UVA graduates each year, sending them into the world without a proper course of study on race makes the university complicit in the maintenance of white supremacy in our society.

I made this argument and again asked audience members if only particular brands of white supremacy appalled them or whether they cared about it in all its forms. I asked if they were bothered by the white supremacy evidenced in the university’s employment trends: people of color are mostly in custodial, grounds keeping and food service roles there, while the overwhelming majority of deans, faculty members and senior-level administrators are white. That is white supremacy, too, I tried to make them understand.

My hour on stage concluded with a plea for outraged UVA employees to make four commitments: (1) this university will confront its historical and present-day racism, (2) this university will not graduate racists, (3) alumni of this university will not be sustainers of racial inequity in our society, and (4) white faculty members and administrators will play a major role in fighting white supremacy. To begin the process of enacting these commitments, I suggested the university must design a high-accountability process of racializing its curriculum, develop a cohesive series of race-focused out-of-class learning experiences for students and engage in departmental and campuswide conversations about race. Given the racial composition of the UVA faculty and staff, I emphasized this work cannot be left to the handful of people of color -- whites must be meaningfully engaged.

The audience offered a thunderous, embarrassingly lengthy standing ovation at the end. Hopefully that means I helped inspire them to correct all manifestations of white supremacy on campus and to use curriculum as a strategic resource to more responsibly prepare anti-racist UVA graduates.