You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

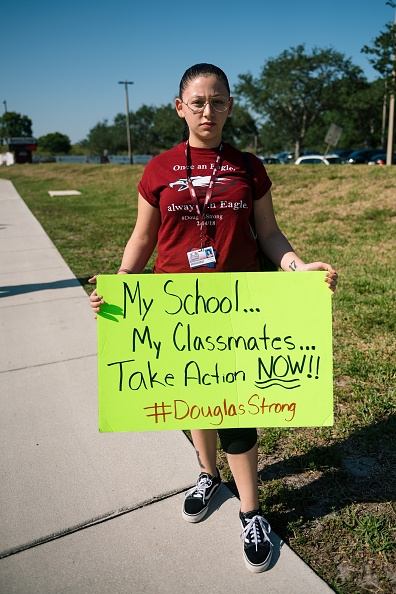

A student protesting the February shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School.

Getty Images

Across the nation, high school students are now selecting the colleges and universities where they will spend the next formative chapter of their lives. They are making their choices against a backdrop of unprecedented public attention to gun violence, thanks to a bold and galvanizing uprising that they themselves have led. While they are high school students today, they will be college students next. Higher education has to be ready.

To understand the students soon coming to our campuses, it helps to acknowledge some essential facts that have shaped their coming of age. The 18-year-old students graduating high school this spring have known schools as sites of violence their entire lives. They were born the year after the Columbine, Colo., massacre. They were seven years old when a shooter killed 32 people at Virginia Tech, one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history. Most weren’t even teenagers when a 20-year-old shooter killed 26 people at Connecticut’s Sandy Hook Elementary School. And while mass shootings receive wide attention, other forms of ongoing “silent violence” shape the lives of thousands of students in their schools, neighborhoods or homes.

How can higher education support students and help advance the movement they have started to prevent gun violence in schools?

First, as new students arrive on our campuses, we must recognize that many come to college without the sense of a classroom as a place of safety, something we know is essential for teachers to teach and students to learn. Some students have experienced gun trauma directly, while virtually all have been affected through news reports and social media. They seek -- and deserve -- explicit institutional commitments to their safety. Those commitments might take the form of emergency preparedness drills, active and repeated safety training for faculty and staff members, and detailed planning around emergency protocols in the classroom and residence halls. It involves counseling services and other forms of trauma-informed mental health support.

Second, we must support our faculty in making space in the classroom to acknowledge incidents of violence. Even when the topic is far outside the faculty member’s discipline or comfort zone, even if the approach may be tentative or awkward, students feel supported when professors acknowledge traumatic events. In reference to the Sept. 11 attacks, research by Therese A. Huston of Seattle University and Michele di Pietro of Carnegie Mellon University has found that students believe it is always best to do something rather than nothing, “regardless of whether the instructor’s response required relatively little effort, such as asking for one minute of silence … or a great deal of effort and preparation, such as incorporating the event into the lesson plan or topics for the course.” In my experience as a professor and a president, students are grateful when you acknowledge events that are hard for them to process.

Finally, as college and university leaders, and as campus communities, we cannot be silent about school violence. Students are leading a bold, essential movement against gun violence, and we must stand with them. We must amplify their voices and join them in demanding change. Many college and university admission deans set this tone pre-emptively in the wake of the shooting at Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School this spring. They made explicit public pledges not to penalize prospective students -- even if the students’ high schools chose to -- for their activism.

Gun violence is not a partisan issue. It is a human rights issue. Every educator should care about the prevention of gun violence -- indeed, violence in any form -- that cuts short the futures of young people, many as their educations have barely begun.