You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

These days, students seem reluctant to engage with disturbing material, and well-meaning professors too often cater to their preferences, shielding them from what they'd rather not confront. Last semester in a history of Asian literature survey class, I had an encounter with a student that challenged both of us -- professor and student -- to rethink our positions.

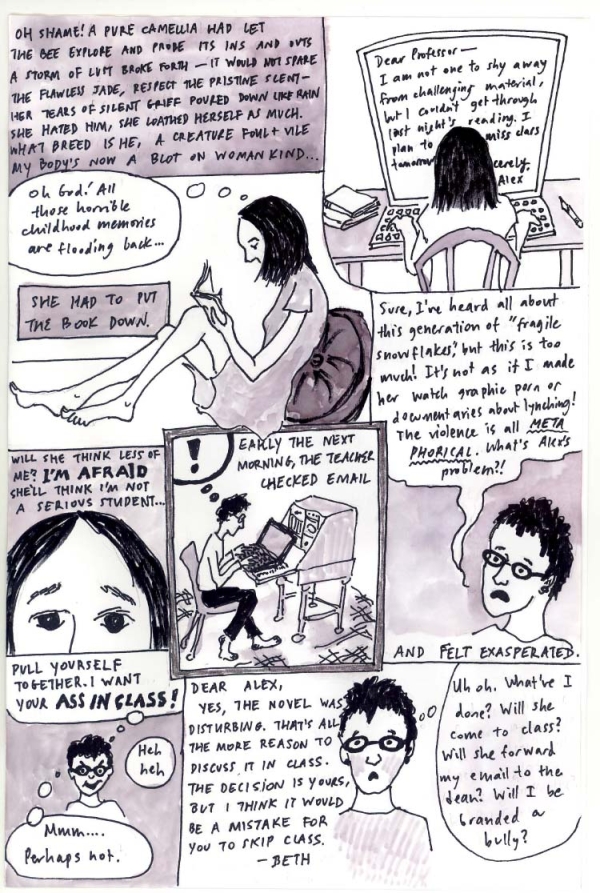

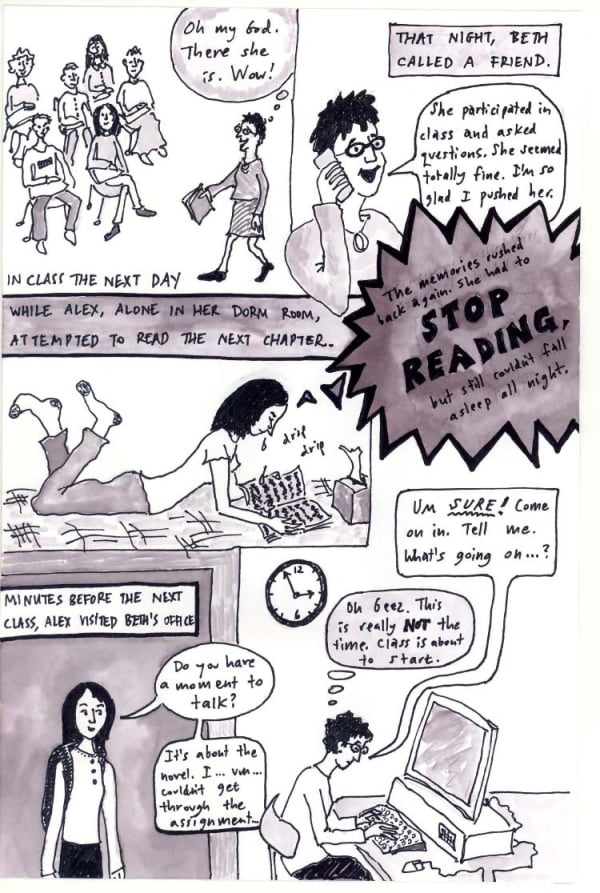

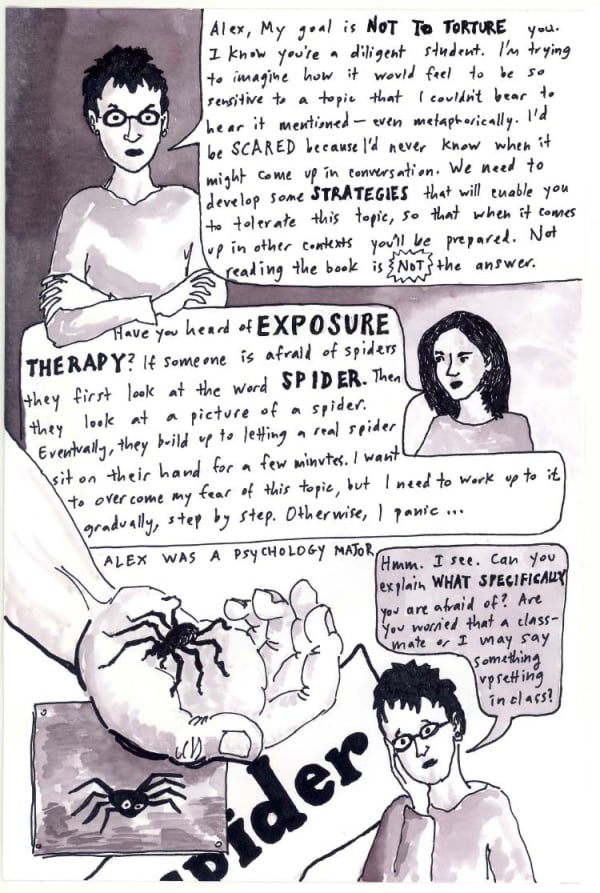

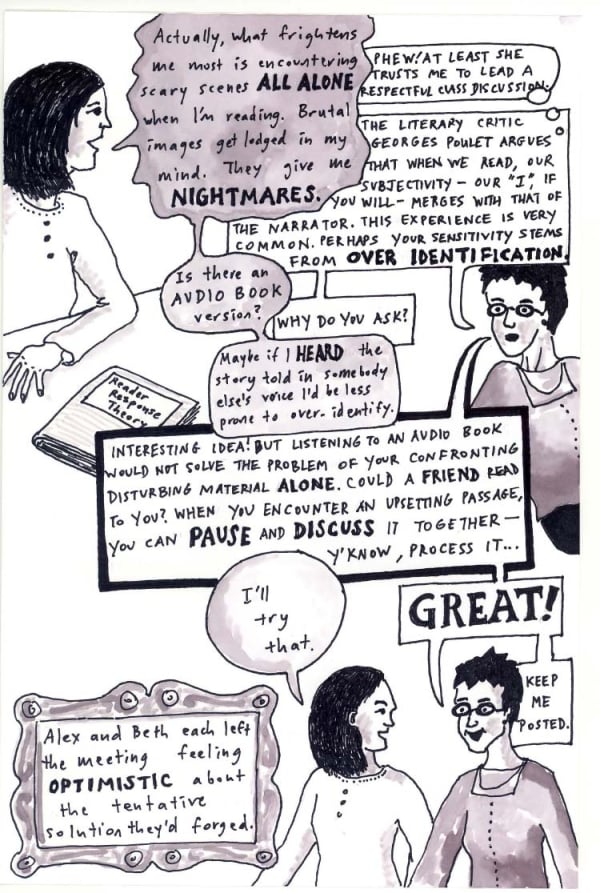

As this graphic treatment depicts, without any trigger warning -- being a graduate of the University of Chicago, I avoid them -- I assigned my class the 19th-century Vietnamese novel The Tale of Kiều. This novel contains many highly metaphorical descriptions of rape. One day, an excellent student emailed me saying she found the content upsetting and could not bear to come to class. I was shocked and dismissed her concerns as excessive. Unwarranted. Or rather, I felt that the only way I could condone her hypersensitivity would be if I knew about her past. Such a reaction might make sense, I supposed, if she had been assaulted herself. But I could not ask. How then, I wondered, could I possibly adjudicate whether her sensitivity was justified or not? And how could I respond appropriately?

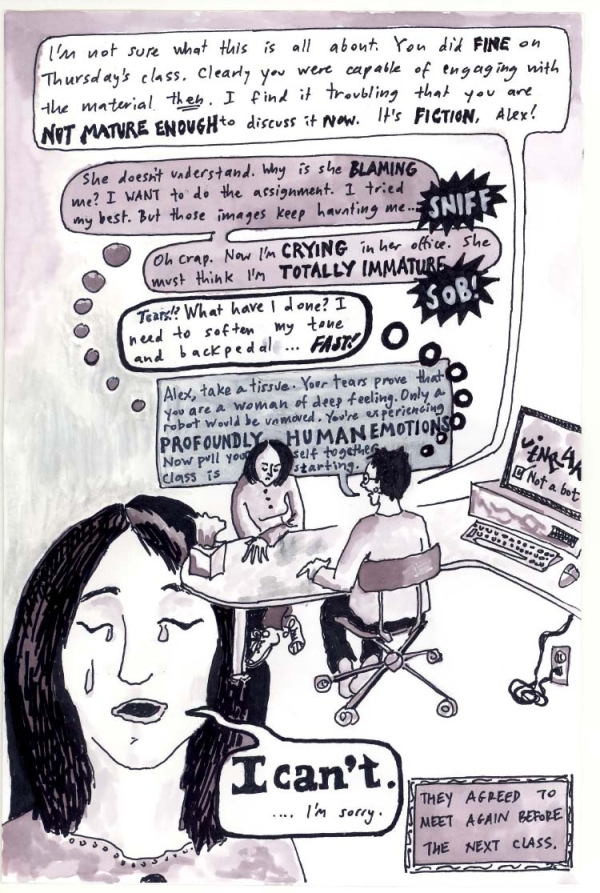

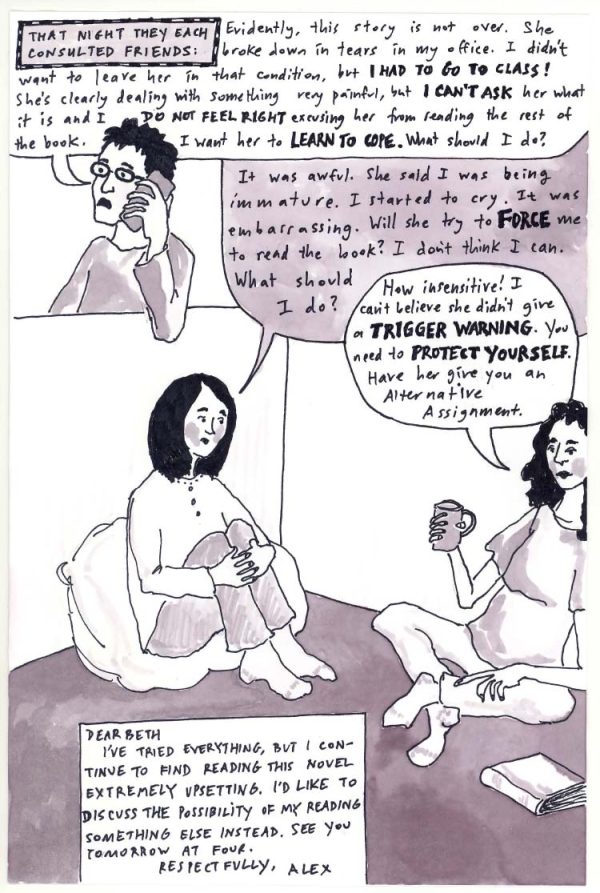

We scheduled a meeting, and she broke down in tears in my office. At that moment, I realized that her present state, not her past, was my concern: I had in front of me a young woman who, for whatever reason, was profoundly disturbed by even the poetic suggestion of sexual violence. Her feelings were powerful and real. And they needed to be respected no matter what experience, real or imagined, underlay them. My job was to help her develop strategies for engaging with a text she obviously found extremely disquieting.

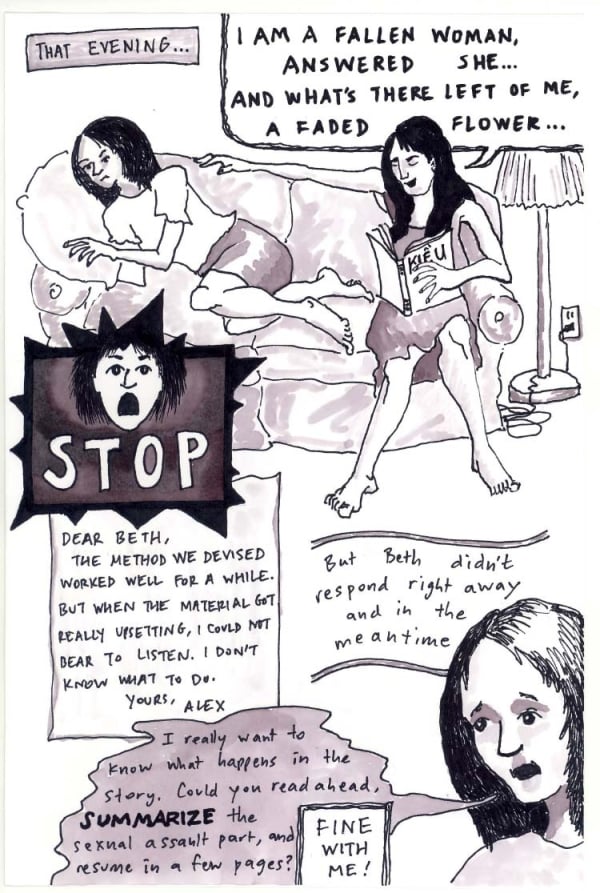

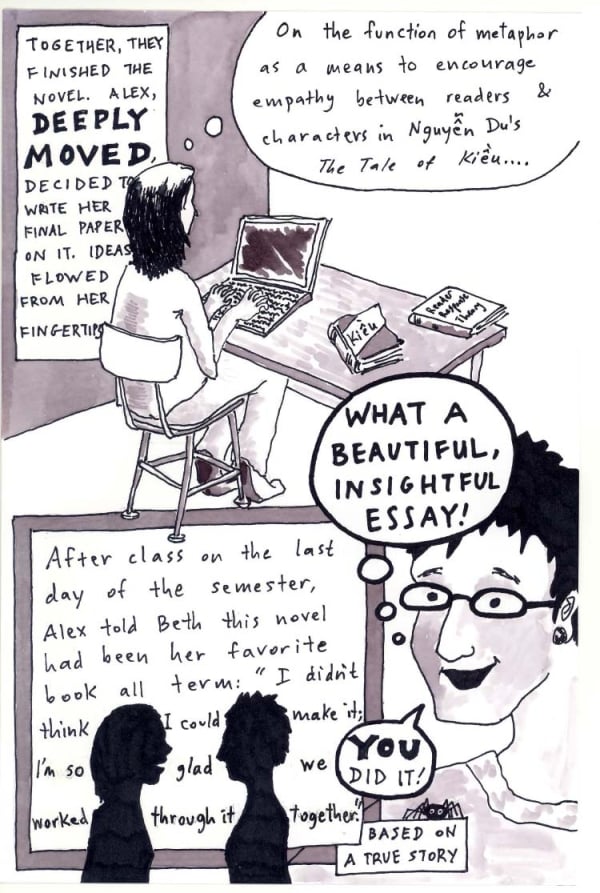

Over the course of more than a week, we discussed her situation several times both in person and online. We also each sought out trusted confidantes with whom to analyze our ongoing interactions. This iterative process was essential, and through it, we moved closer to understanding one another's points of view. I choose to express the story visually here because doing so challenged me to imagine our interactions from both the student's perspective and my own. Drawing -- especially the thought bubbles -- prompted me to imagine her perceptions and to envision her thoughts, fears and concerns.

The story as told here exhibits my greatest hope for students: that they will learn to titrate their own exposure to content they find disturbing, and that they will eventually wean themselves off the need to rely on professors’ or other authority figures’ trigger warnings or “opt-out” assignments. In the end of this story, it is the student herself -- not the teacher -- who comes up with the best strategy for approaching the text. Students must gain this independence, as eventually they will decide for themselves what to read and how to read it. They will take responsibility for balancing between protecting and pushing themselves.