You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

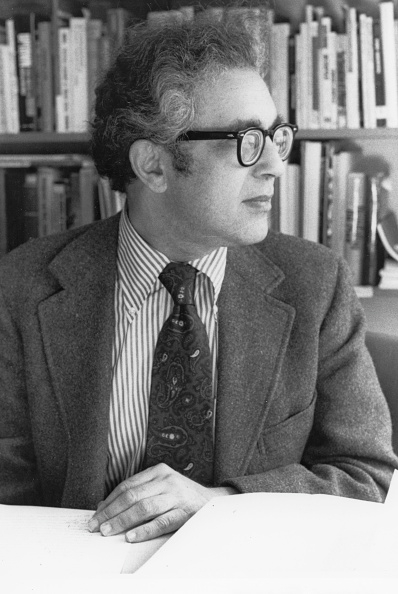

Nathan Glazer in 1981

Getty Images

Nathan Glazer, one of our nation’s leading urban sociologists, passed away Jan. 19. His scholarly accomplishments were legion and well-known -- at least, for the most part. But what many people may have been overlooked were his contributions to the growth and development of Harvard University Press.

To talk about what I think Nat meant to the press requires that I back up and set the stage. Harvard University president Derek Bok appointed Arthur J. Rosenthal the director of the press in 1972. There was some pushback from the faculty. Why bring in a commercial publisher to head an academic press? But Derek stood strong.

In time, Arthur brought a contingent of scholars, including Nat and Daniel Bell, who’d first met at the lunchroom of City College in the 1930s, then became Harvard professors, and finally, thanks to Derek and Arthur, came to lunch with the Board of Syndics of the Harvard University Press. Syndics -- a fancy, if you will, old-fashioned word -- are members of the faculty whose job is to decide over lunch, as I hinted, if the books the press wants to publish are of good enough to carry its brand name.

The appointment of these City College friends to the Syndics matters in the history of the press, because this parochial contingent of New Yorkers brought, paradoxically, a worldliness that lifted the press up. They might have looked and sounded like Statler and Waldorf, the opinionated elderly gentlemen who enlivened the crew of The Muppet Show with their wisecracks from the balcony. Yet their effect was to serve as two booster rockets for the press, as when Harold Ross came from the boondocks and started The New Yorker, to which he gave an extraordinary worldliness. And they just plain made Arthur, a New Yorker himself, feel comfortable.

Harvard University Press had published numerous distinguished books before Arthur and the City College boys arrived, and its Board of Syndics had featured many great scholars, but the special sauce was missing. Of course, it helped that Arthur had recently become the director and Lincoln specialist David Donald had moved from Johns Hopkins University to Harvard with his wife, historian Aida, who was appointed history editor at the press -- and thus the press gained in strength because of the possibilities for coordinating its efforts with the heart of the faculty.

Nat’s tenure on the Board of Syndics coincided with a golden age for the press, one he helped make happen. The story of his and Daniel Bell’s lives at the press has for me, a militant Midwesterner, the aura of a New York City story. If I could, I’d cue up now the song of Alicia Keys and Jay-Z, “Empire State of Mind”: “In New York, concrete jungle where dreams are made of/Big lights will inspire you/There’s nothing you can’t do./The streets will make you feel brand-new.” Of course, Nat’s life work as a sociologist was devoted to the mean streets of New York that Jay-Z sings about.

Nat’s life is a story with some zigzags to it. He grew up as one of seven kids on the Lower East Side, and he had to work his way to the Upper West Side, to City College of New York and eventually to Columbia University. His most important book, written in 1963 with Daniel P. Moynihan, was about the different peoples who make up New York City: Beyond the Melting Pot: The Negroes, Puerto Ricans, Jews, Italians, and Irish of New York City. Nat worked in publishing for years -- first at small journals and start-ups before becoming an editorial assistant to Jason Epstein at Doubleday.

Nat was always a person who zigged and zagged in a way that irritated many of his academic and political friends. He was an inductive thinker, not a theorist and not an ideologue. It endears him to me, but that is because I have been happy to see him deviate from any neoconservative orthodoxy some people thought he should have adhered to. He did not stick with all his City College buddies. He broke with Irving Kristol when Kristol became too doctrinaire and shrill as an ideologue attacking the left-of-center position of multiculturalism Nat came to advocate, even writing a manifesto in favor of it in 1997 called We Are All Multiculturalists Now. He did not hide his differences from friend or enemy. He kept his bearings by not being rigid. John Maynard Keynes said, “When the facts change, I change my mind.” The same was true of Nat.

They say in the 12-step programs that we do everything the way we do anything. Listen to this New York City story about Nat Glazer that seems as beautiful to me as the wonderful Boston story Make Way for Ducklings by Robert McCloskey. It’s just waiting for a children’s book author and illustrator to put it on paper. Here goes:

Nat was a sociologist who specialized in cities, and especially one city: New York City. If you know the book Make Way for Ducklings, you will undoubtedly know an equally lovable book, Hildegarde Swift’s The Little Red Lighthouse and the Great Gray Bridge. Nat had three little girls. Here is where his ability to zig and zag really came in handy. As his daughter Sarah wrote me, “My parents’ bedroom had a view of the Hudson River, and [we] grew up sledding and cycling in Riverside Park. Whenever we drove out of the city, we always took the Henry Hudson Parkway and drove past the magnificent George Washington Bridge, which I imagine my father made sure we’d admire.”

“When my parents divorced, my father would take us every Saturday on a different excursion exploring the city -- always by mass transit,“ she continued. “So one day, he announced we were going to the Little Red Lighthouse. We took the bus uptown -- to 175th Street, I guess-- got dropped off on the Henry Hudson Parkway and had to cross four lanes of fast-moving traffic to make it to the lighthouse, which we could see on the other side. Even at that age -- I was probably 8, Sophie 7 and Lizzie 3 -- I knew that was a crazily dangerous thing that most parents would never have attempted. But I also loved his determined spirit of adventure that got us to our beloved storybook lighthouse. To be honest, I couldn’t see any other way to get there.”

If Nat had been a rigid person, he and I would never have become friends. I suppose you could say the same about me. I was a student radical in the 1960s. He and I were on the opposite side of the ’60s barricades. We confronted our differences late in our relationship, because that was the time when we began to see more and more of each other. I thought of Nat and Daniel Bell as a dynamic duo, late into their lifetimes. At first I was closer to Dan. Dan especially took it as his task to guide me by peppering and salting me with advice on my proposals to the Board of Syndics, where he and I developed a very effective, if somewhat hilarious, working relation, which led the press to publish Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces, as well as 3,000 pages of the writings of Walter Benjamin and much more. My Baedeker for those decades was Dan’s Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. The road was not straight and narrow -- instead it had many twists, just as there were in Nat’s political journey.

After Dan died in 2011, Nat and I made occasions to meet more and more. The baseline of our talk was always books, publishing and literary journalism. He was a voracious reader -- he put me to shame. In recent years, Nat’s health was better than mine, and it stayed good for years because his wife, Lochi, kept him walking all over Cambridge -- for example, to Peet’s for coffee and to Adams House for the Christmas-Hanukkah Fest.

In those years, I had a couple of big medical operations -- real tsunamis -- and he came to visit me in Mount Auburn Hospital and after my operation at home. The operations were tough, but Nat clearly was becoming decrepit, stooped over with age. I asked, “Why do you visit me, all the way to Watertown?” And he said, “It’s a mitzvah.” Not a bar mitzvah, but a mitzvah, a duty, one he happily performed.

Once, when he came to visit me after my quadruple bypass, we got a seminar running with my old Harvard University Press colleague Mike Aronson and Syndic Bill Todd, and all at once, we were transported back to the lunch hall at City College in Alcove 1. We talked about the great editor Elliott Cohen, the founder of Commentary, who’d published Paul Goodman, author of Growing Up Absurd, and James Baldwin, among others.

Another time, at his house, I asked him about his move to the University of California, Berkeley -- then it was 2017 -- and he loaned me a copy of his 1970 book, Remembering the Answers: Essays on the American Student Revolt. I worried. This was dangerous ground for us to tread on, I felt -- soil where there were land mines that might blow up under our feet and kill our friendship. But instead, our opening up this subject for discussion brought us closer. I read in the book how he had reacted to the student revolt at Berkeley. He had been repulsed by the passion in some of the students for “confrontation, for humiliation of others.” But I recognized that those thoughts of his were the same I had had when I rejected the recommendations of some of my fellow students at Providence College when I initiated the PC Students for Peace in 1967, and when I refused to join the SDS and to perform violent protests at the Democratic Convention in 1968 or at the Pentagon in the fall of ’68.

I discovered, thanks to his lending me his book and our talk, that we shared a common instinct to retreat from the brink that attracted others like a drug. I found that extremely attractive in him -- a balance and measure. Long after the ’60s, Nat’s old friend Irving Kristol wrote aggressively and militantly against multiculturalism in The Wall Street Journal. Nat never lost his ability to write provocatively, but he refused to write ideologically. In the midst of the school-busing crisis in Boston in the ’70s and ’80s, when I first came to the Harvard University Press, he rejected the rigidity of federal judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr.

There was a sinuous rationality and sensibility to Nat’s body and mind that appeared in his social policy recommendations that enabled him to weave through the difficult terrains just as he had done shepherding his little girls through the many lanes to traffic to reach the Little Red Lighthouse. May his light and example guide us for decades through the darkness that has now befallen our country.