You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

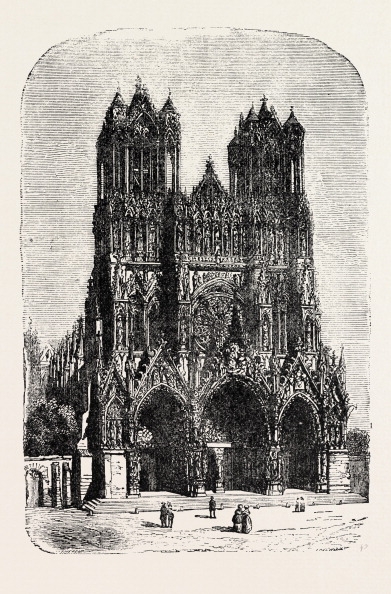

Reims Cathedral

Getty Images

Back when I was working in my university’s graduate school, I went to a lot of recruiting fairs. Sending me, a tenured academic administrator, was an unusual approach to recruiting -- most of my fellow recruiters at other institutions were staff members. Often they were relatively young and ambitious. For many of them, moving up in the staff hierarchy meant getting an advanced degree of some sort. So I often found myself trying to sell other recruiters on our graduate programs.

One such encounter has stuck with me. On that occasion, a recruiter asked me if my institution offered any online doctoral programs. He wanted to advance at his university but felt he needed a doctoral degree to do so. We had spent several hours in adjoining booths, and he seemed smart and earnest.

At the time, we did not offer an online doctorate in anything, and none of our doctoral programs were in his intended field, so I switched from a recruiting mode to that of an adviser/mentor. I tried to convince him of the virtues of a face-to-face program by telling him that much of what one gains from a doctoral program comes from the experience of being there -- the interactions with other students and the opportunities to hear guest lectures, to be a grad assistant and immerse oneself in the culture of a discipline and department. I told him that -- fairly or unfairly -- people don’t take online degrees as seriously as traditional degrees, and that if he was really committed to doctoral-level grad work, he would have to leave his job and go to grad school.

Our conversation soured immediately. He told me, a bit huffily, that he needed the degree but didn’t have time to go to graduate school. He had an online Ed.D. program in mind and was going to pursue it.

I experienced many variations of that discussion in my recruiting days. They all boiled down to this: someone wanted a college degree but did not want to go to college.

A whole industry of online program mangers, or OPMs, has grown up to help colleges tap in to this market. They often focus on master’s degrees in fields where graduate degrees have become commodities. Education is a good example. Graduate degrees qualify teachers for pay raises, for specific types of teaching jobs or for the chance to move into administration. As long as the degree is from an accredited college, the school systems typically don’t care about the reputation of the college or program the degree came from. That has created intense competition among colleges to offer those degrees as cheaply and conveniently as possible -- which means they often end up delivering online courses with as little rigor as you can get away with without falling afoul of the accreditors.

A college degree once required that you be physically present. For most people, that meant leaving their home and family to move to another city or town, giving up employment and other obligations, and joining a new community of fellow scholars. In many respects, going to college was like going on a pilgrimage. You left home, joined a group of like-minded pilgrims and went on a journey together. When the journey was over, you returned home to family and work, transformed by your experience.

For many students, especially those who attend elite institutions, that is still what college is like. (Anyone tempted to object that college life is more bacchanal than pilgrimage should give The Canterbury Tales a quick reread. Medieval pilgrimage was not entirely pious contemplation.) But many potential students, like the recruiter I met, feel they have no choice but to skip the journey and choose to just knock out the degree online. Modern life, we are told, is simply too busy and complex to expect people to make time to go to college.

Colleges that cater to this market do so without apparent shame. Rather they tout these products using words like "innovation," "disruption," "accessibility" and "equity."

They do so at their peril.

Selling Indulgences

Five hundred years ago, a similar “innovation” caused the Roman Catholic Church a world of trouble. Just as the modern university has a monopoly on the vitally important credentials that allow access to middle-class jobs, and thus salvation from the precarity and low status of the degreeless, the church alone had the power to grant penitents absolution of their sins. Traditionally, an act of penance was required to gain that absolution. That might be something as small as saying a few Hail Marys and a couple of days of fasting or something as big as a pilgrimage.

But the late medieval period was a busy time. Between boxing the apprentices’ ears, keeping an eye on the serfs and staying abreast of the rat race in the counting house, what sinner really had time to drop everything and spend a year or two slogging around the pilgrimage routes?

So change agents in the church (the “pardoners,” who were the church’s sales force) disrupted the salvation paradigm and devised an innovative new solution that delivered absolution in a way that fit the constraints of the busy medieval lifestyle.

They started selling indulgences that effectively allowed penitents to skip all the tiresome fasting and trudging to the tombs of saints and just pay for their absolution.

The church used this income in ways that will sound familiar to the modern academic. Above all, it built buildings. One of the towers at the Reims cathedral is known as the “butter tower” because it was paid for by the sale of indulgences allowing people to eat butter during the Lenten fast. The income from indulgences also helped to keep bishops, the princes of the church, living in luxury.

The most famous of those pardoners was Johann (or Johannes) Tetzel, who was charged with raising money for the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica, which was the pope’s home church. Tetzel was an aggressive salesman who is said to have produced the jingle “as soon as the coin within the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs.”

While some people no doubt welcomed the opportunity to buy their way out of sackcloth and ashes, it also made many people cynical about the church and created doubts about its priorities. Martin Luther gave voice to those doubts in his 95 Theses, the 27th and 28th of which directly and scornfully referenced Tetzel’s sales pitch. Luther and his supporters were unhappy about many aspects of the church, but the sale of indulgences ranks high among the causes of the Reformation.

The modern university has its origins in the medieval church. Most American universities are no longer closely affiliated with churches, but the public still sees us as separate from mainstream society. Thus, we have terms like “ivory tower.” Sometimes that term is used pejoratively, but it also reflects the notion that the university, like the church, is supposed to have a higher purpose. That creates expectations, one of which is that we won’t behave in crassly commercial ways or exploit the power that we have to grant degrees that are every bit as important in our time as indulgences were in theirs.

The public is growing ever more cynical about higher education. We feed that cynicism when we hire Tetzel-like OPMs to peddle our new quick and easy, no-muss/no-fuss online degrees. This aggressive and unseemly salesmanship is already generating negative press. We feed that cynicism when we use that income to spend more and more on our bishop-like administrators and their beloved buildings, while adjunct faculty -- the parish priests of the university -- languish in poverty.

Worse, the response to public concerns about higher education often is to try to become more convenient, more customer focused and more accessible. That is the wrong response. People want and need real rites of passage. Our strong suit is the pilgrimage, the journey, and we ought not forget it.

And we should not be surprised if the real challenge comes from reformers that are more Luther than Tetzel. It may already be happening. A recent Molly Worthen article in The New York Times described what she calls “anti-colleges” that cater to people who want an education that is more pilgrimage than product.

If a movement comes along that poses a serious threat to the status quo in higher education, it may come from someone offering an education that seems like a step backward to a more traditional college experience rather than something that is more convenient and technology driven than what we now offer -- something more Lutheran or Franciscan and less Tetzel.

That will be a good thing. Higher education is ripe for a Reformation.