You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

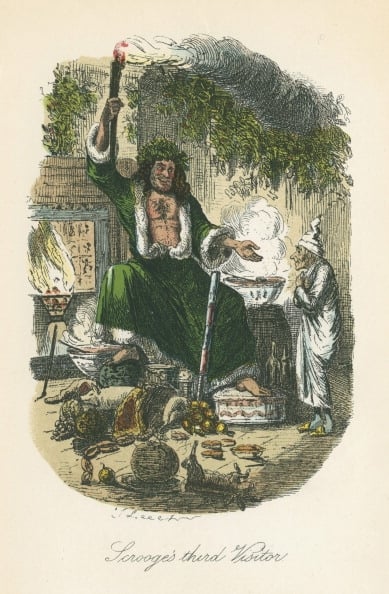

Illustration by John Leech for Charles Dickens's 'A Christmas Carol'

Getty Images

In Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, Ebenezer Scrooge, haunted by the Ghost of Christmas Past, revisits scenes from his life, some tender, some tragic. He re-experiences the loneliness of boarding school, his father’s cold disapproval and the warmth and kindness of his sister and his mentor, Fezziwig. He watches passively as his former fiancée ends their relationship. “These are but the shadows of things that have been … they are what they are,” the ghost says.

The question becomes whether or not Scrooge will see past events as lessons that lead to transformation. Today, higher education finds itself in a similar position.

Reviewing the history of higher education reveals the shadows that shape our situation today. The nation is experiencing a period of societal transformation as significant as the Industrial Revolution, when a relatively new country transitioned from a local, agrarian way of life to a national, industrial society.

Driven by invention across the manufacturing, agricultural, communications and transportation sectors, and by immigration and concentration of labor in urban settings, the first industrial revolution created demand for a differently skilled workforce, forcing debate over -- and ultimately a transformation of -- the composition of higher education. The process of change involved invention, application and scaling up followed by standardization and consolidation at a level never before realized.

Then, as now, America's colleges were products of the passing era. As the society around them changed, they came to be perceived as out of touch with the times. From the 1800s through the mid-20th century, higher education transformed to meet new realities through a disorderly process that included eight overlapping stages:

- demand for change;

- denial of the need to change;

- experimentation and reform initiatives attempting to repair the existing model;

- establishment of new models of higher education to replace the existing model;

- diffusion of the new models, led by a prestigious institution, Harvard University, with other mainstream institutions adopting similar changes;

- consolidation of the major changes promoted by a new institution, the University of Chicago, organically linking the successful elements of the various initiatives;

- standardization of the varying practices and policies spawned by diffusion; and

- scaling up and integrating the various elements of now standardized practice and policy to create a new system of higher education.

Based on historical analysis, I would offer some thoughts about the future of today’s higher education in the United States.

Looking back primarily tells us how change will happen, not what will happen or how quickly it will take place. It won’t take place seemingly overnight, like Scrooge’s transformation, yet it probably will take only a fraction of the 150 years that shaped the current system. The present looks very much like the antebellum era. We are witnessing demands for change, the denial of the need to change and myriad institutional reforms and experiments. We are still testing new ideas that ultimately will lead to new models, just as after the Civil War we saw three major models emerge:

- the exemplar land-grant institution, Cornell University, which embedded the best of a classical education into a modern university rooted in practical and advanced studies, student choice, and expanded access;

- the first great graduate school, Johns Hopkins University, which paved the way to the faculty-centered university; and

- the first great applied-science institution, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which prepared technologists for the new economy.

As yet, we can speculate, but we lack agreed-upon models. There is nothing obvious to consolidate, standardize or scale, though some candidates are emerging. The shift from the industrial model of courses, credit hours and seat time to an information-economy model of learning outcomes with individualized, technologically powered paths to reaching them, is leading to a competency-based design for education.

The future will emerge from Bob Cratchit’s house, not Scrooge and Co. The sociologist David Riesman once noted that academe moves like a snake, following the head (elite institutions). But today, leadership for change is based in the tail. It resides in the institutions where Cratchit’s kids would go today: online colleges, community colleges and for-profit institutions, as well as small, less selective, private colleges facing declining enrollments and seeking life rafts. The most successful of these innovations will diffuse up the academic snake, finally being adopted by the least prestigious units of the most prestigious universities, such as continuing education. This was the process by which higher education began enrolling nontraditional students and establishing programs for them in the 1970s.

The other major venue for change will be institutions, principally in the Sunbelt, with the opposite problem: ballooning college-age populations that are growing faster than their current physical campuses can possibly accommodate. California, for example, will need to consider virtual campuses such as the virtual community college it has created, changes in the academic calendar and clock, new approaches to staffing, massive online instruction, and much more.

Change will not replace but rather modernize current institutions. In the past, for example, America’s four-year, residential, liberal arts colleges remained a vestige of colonial colleges but with new organization, staffing, students, curriculum, methods of instruction and assessment. Previous transformations created new forms of higher education -- universities, technical and scientific schools, and junior colleges -- that quickly dwarfed the remnants of the old agrarian system. What remained was modernized rather than discarded. This seems likely to be repeated, with vestiges of the current system remaining alongside new models.

As our society becomes more fragmented and divided, we have reason to worry that changes in higher education may further fragment us. College is likely to be an increasingly individualized experience aimed at connecting people to new uses of knowledge but not common knowledge. ”All things considered” may soon become “one thing considered,” with each person determining what they want that thing to be.

The problem is at least twofold. First, national commonality has splintered, shared beliefs have dissipated and new technologies promote atomization as well as new communities. Second, historically, general education movements occur in times when individualism in the nation is high and rising. It is an antidote.

Today, general education is dated, rooted in the passing era. We need to rethink general education and recast it in the heritage and skills essential for the 21st century, And as we transform our higher education system, the ghost of Higher Education Past can be a useful guide and ally to those in higher education who are open to its lessons and warnings.