You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

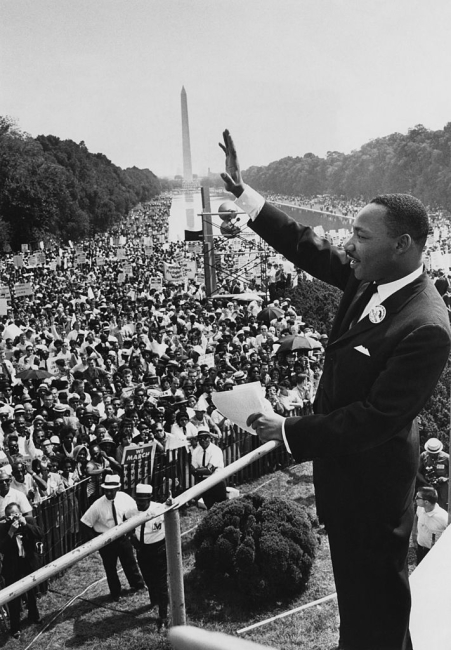

Martin Luther King Jr. delivering the "I have a dream" speech on the Washington Mall in 1963.

Hulton Archive/stringer/Archive Photos/Getty Images

I did something recently that I have never done before, something I never even considered I would do. I declined an invitation to speak for a Martin Luther King Jr. program.

As a preacher’s kid who grew up in Atlanta, someone who has met most of King’s lieutenants, I had long viewed every King Day invitation I received as a solemn responsibility. It was also an obligation to have the audience explore King beyond the traditional sound bites, so I prepared reading different speeches or looking for new passages in books by or about him.

So why did I decline this year? I didn’t do so because I had a schedule conflict, or that we couldn’t make the program work due to the risks associated with COVID-19. We found a date that worked, and I could speak virtually.

I said no because a governmental agency invited me. They sent me a speaker certification form, which reminded me that then-President Trump passed last fall an Executive Order on Combating Race and Sex Stereotyping. I had never thought I would be confronted with it. The order prevents speakers from addressing what they call “divisive concepts,” as well as race stereotyping and scapegoating.

Even though the language was broad -- probably too broad, so that someone could claim a speaker violated the order -- I knew I had the ability to craft a compliant speech. But in my Twitter bio, I say that I am a transformed nonconformist, a reference to King’s 1954 sermon in Montgomery.

So I declined.

We recently witnessed a mob of white supremacists storm the Capitol, killing a police officer and several other people during the siege, defiling the building while looking to attack lawmakers. In light of that, was I supposed to give some sanitized Martin Luther King Jr. “content of your character” speech? King would not have given that speech this year.

In his book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, he explicitly mentions white supremacists. In fact, this 1968 text is quite relevant today, as he mentions that Southern segregationists were concerned about increases in Black voters, saying that white supremacists temporarily held statehouses in Georgia and Alabama. He indicated that underprivileged whites struggled with segregation and economics, saying, “White supremacy can feed their egos but not their stomachs.” Today, it feeds their egos while the coronavirus gorges on their respiratory systems and their finances.

Revisionist history paints King as someone beloved the world over, while the truth reveals that during his last year of life, he was one of the most hated people in the nation -- by both Black and white people. That’s because King spoke honestly to the issues of the day.

I explored some of those ideas in past King speeches I have given. In 1967, King spoke to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, where he argued that Americans had an unenforceable obligation to each other if we were going to end racism. Fifty years after that speech, I spoke about how this obligation was crucial as a new administration was coming in, led by someone who made it clear his brand was division. King defied German authorities and preached on both sides of the Berlin Wall in 1964. I used that speech as the basis for a King Day speech two years ago while we had a president trying to build his own wall.

When the Trump administration released the new executive order, higher education cried foul. But that’s it. We cried. We did not more forcefully oppose the policy, knowing that it had potential to impact our broader goals. We didn’t push back harder when Trump rolled out the now-ridiculed 1776 Commission. We didn’t more forcefully oppose the U.S. Department of Education’s investigation of Princeton University for trying to examine its racial past. I can only think our tepid responses emboldened the executive order on race and sex stereotyping.

While, philosophically, higher education will better align with the Biden administration, we need to practice being more like King rather than simply offering statements that he once made. Yes, a level of risk is involved and a degree of courage is required, as well as a willingness to break some of the norms of higher education. But if we believe what we wrote in our flowery statements after the death of George Floyd, we must start practicing with our actions.

I never imagined I would decline giving a King Day speech because a presidential executive order would potentially limit what I could discuss related to race. Anyone who has read King’s work extensively knows he challenged people in ways that made them uncomfortable, so uncomfortable it got him killed. Now that the order has been rescinded, we must work to build an America where we live in such a way that a King Day speech won’t be censored. We must create a beloved community willing to wrestle with tough issues.