You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

After months of managing the pandemic, it is not entirely surprising that college and university faculty members and administrators are exhausted and stressed. Institutions have had to respond to immediate and pressing needs regarding safety, health and online technology, as well as navigate concerns articulated by different stakeholders -- including students, parents, faculty, staff and trustees. And with vaccines now being distributed, they may be looking forward to “going back” to the world as it was.

Yet this is precisely the moment when colleges and universities must turn to more active and strategic approaches to support faculty members, given the differential impacts of the pandemic on faculty careers. Without engaged interventions, higher education post-COVID will most likely be less diverse, given the pressure the pandemic is placing on women and faculty of color.

As members of the UMass ADVANCE team, funded by the National Science Foundation, our focus is primarily on creating institutional transformation to ensure long-term gender and racial equity in STEM. With the pandemic, we have focused our attention on how institutional responses to COVID-19 can mediate the impact and remain attentive to the important goals of equity, diversity and inclusion.

The Problem and Our Solution

The pandemic has exacerbated gender inequality, as women have reduced their work hours more than men due to schooling and caregiving demands. In higher education in particular, women faculty members and those with children have been less likely to submit grant proposals and journal articles or register new projects. More and more faculty members fear a secondary epidemic of lost early-career scholars.

During this time, minority women and mothers have been most impacted. Black, Indigenous and Latinx communities have been particularly hit hard by the pandemic in terms of health risks and unemployment, increasing stress, and caregiving responsibilities. BIPOC faculty members are also more likely to be conducting community-engaged research, which has faced additional pandemic interruptions, while also working to support their communities. Many women and faculty of color have also been on the front lines in supporting vulnerable students, with Black, Indigenous and Latina women particularly burdened with mentoring and service work.

Other differential impacts of COVID-19 reflect a faculty member’s field of study, methodological approach and a host of other variables. Many faculty have been cut off from data collection for months. That has meant halting vital experiments and longitudinal studies, being unable to carry out field research or archival work that requires travel, and losing important time on grant-funded projects. All of those circumstances have been devastating for research programs. At the same time, some scholars in other research programs may have found themselves with more time for research. Faculty members in the same department may be in very different positions vis-à-vis pandemic impact on their scholarship, depending on their approach to research.

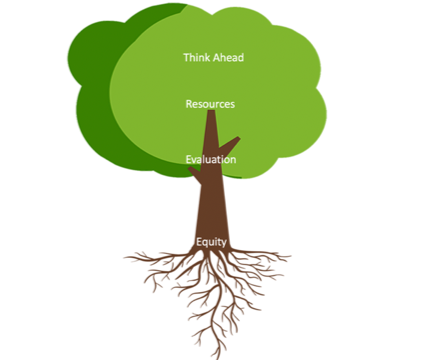

In this piece, we will highlight our TREE model of institutional response to COVID-19 as an approach that higher education leaders can take to ensure that equity and inclusion are not lost in the pandemic. The TREE model emphasizes thinking ahead, resource provision, evaluation and equity. It focuses on addressing both short-term and long-term impacts on faculty members to center equity as a goal. By cultivating the ground effectively and establishing the roots of equity, colleges and universities can ensure that faculty members grow through this pandemic rather than have stunted careers.

In this piece, we will highlight our TREE model of institutional response to COVID-19 as an approach that higher education leaders can take to ensure that equity and inclusion are not lost in the pandemic. The TREE model emphasizes thinking ahead, resource provision, evaluation and equity. It focuses on addressing both short-term and long-term impacts on faculty members to center equity as a goal. By cultivating the ground effectively and establishing the roots of equity, colleges and universities can ensure that faculty members grow through this pandemic rather than have stunted careers.

Think Ahead

The first element of our model is for administrators to think ahead -- to consider not only the immediate needs of the moment but also the long-term effects of the pandemic. Colleges and universities have already focused on ensuring online pedagogical tools are working and that campus COVID-19 testing is safe and effective. Another policy that many institutions have adopted is the automatic extension of tenure clocks, giving faculty more time to reach tenure. On our campus, this extension is designed to guarantee that faculty will not lose out financially (those with successful tenure cases will have their salary bonus backdated to the original expected tenure date) and allows faculty members to petition to go up for tenure at the original time if they so choose.

Yet postdocs and new faculty who are setting up their research programs during a pandemic are also affected, so institutions must consider how to apply these policies over the long term. To think ahead, they also must collect data thoughtfully to identify inequalities in the experiences and outcomes of faculty members. That includes consistent data collection and analysis by race and gender of who is hired, who leaves the institution and how salaries and tenure and promotion rates compare before, during and after the pandemic. Colleges and universities should prioritize data collection that identifies what faculty members need in terms of resources and supports to ensure that they can lead successful careers. They should also evaluate the gender and racialized impacts of the policies that they’ve put in place as a result of the pandemic.

Provide Resources

While higher education institutions have struggled financially, they must provide resources to faculty members in the short term to help them through the challenges of the pandemic. One of the most immediate resources that colleges and universities focused on were teaching resources, helping faculty move their courses online. Some institutions, like our own, also provided technology assistance funds. Many have also stopped relying on student evaluations of teaching and moved to more holistic approaches to assess teaching, given that the challenges with moving courses online exacerbated the existing biases in such evaluations. Institutions can also aim resources at addressing technology needs, health care, food and housing security for faculty members in insecure positions.

In addition, faculty can benefit from reductions in nonessential workloads, such as curricular reform or department evaluations. Institutional leaders can encourage shorter letters/memos for tenure and promotion cases. Workload redistribution can also help faculty members who are most vulnerable. For example, adopting approaches that protect junior faculty’s time can pay large dividends. Institutions can repay faculty members who have taken on heroic but invisible work (e.g., moving courses online, helping their colleagues with online pedagogy, mentoring students of color) by giving them additional research funds, teaching support or service sabbaticals. At our own institution, the union negotiated that faculty moving courses online earned credit toward sabbaticals or future course releases.

Faculty members can benefit, as well, from policies that shift how long they can use their research start-up monies. Institutions can target research funds to scholars who have been particularly affected by the pandemic, including caregivers or faculty of color. Funding agencies, of course, can also provide no-cost extensions, more flexible rules for use of funds, longer submission deadlines and new opportunities for early-career researchers, as well as extend faculty members’ timelines as “new researchers.”

In addition, colleges and universities can offer support for caregivers through a variety of mechanisms. For example, they can establish a clearinghouse to help faculty members identify and hire caregivers. The University of Pennsylvania sponsors such a clearinghouse as well as childcare grants. The University of Massachusetts provides childcare and eldercare assistance funds along with faculty leaves to care for family and household members. Flexible working arrangements are another policy that allows workers to adjust to caregiving or schooling needs.

Evaluate

Colleges and universities must adapt how they assess faculty members. The assumption has always been that faculty members all are starting from a level playing field -- which is, of course, untrue. Many evaluation systems compare faculty members to colleagues of the same cohort at similar institutions, measuring, for example, productivity in terms of numbers of articles, citations or grants. The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare the fact that the playing field is far from level, particularly given the collapse of existing systems of childcare and schooling.

Three or five years from now, institutional actors may not remember how much the pandemic reshaped faculty members’ workload and careers. One important approach identifies how to document both the interruptions and the extra work that faculty members have engaged in to guarantee that this record is not lost. UMass ADVANCE has developed a pandemic impact tool to help faculty members document these effects. With the support of the provost and the faculty union, as well as the Massachusetts Society of Professors, faculty now can include information about how these events influenced their annual reviews, which are included in their personnel cases.

But evaluation itself also needs to shift. Rather than comparing two faculty members who may have had different opportunities for conducting research -- for example, those doing theoretical versus empirical work -- evaluators should judge each one’s work in terms of its quality. They should assess scholarly output in relation to each faculty member’s working conditions and the effects of the pandemic on their program. And considering the pandemic impact statements, they should not penalize faculty members whose records look different from other generations.

The impact of caregiving is also tricky. Ideally, faculty members should be able to identify how the pandemic affected care responsibilities, but caregiver bias could work against faculty members who have had such responsibilities. One approach is to train the people who evaluate colleagues -- deans, chairs and personnel committee members -- how to identify bias and assess faculty members fairly. Trainings on our campus this fall were very successful, and we plan to offer them for at least the next two years.

Ensure Equity

Finally, our model rests on the notion that equity must remain the guiding principle of institutional response rather than be sidelined by the pandemic. Instead of seeing the pandemic as “equal opportunity” and affecting all faculty members the same, we must recognize its differential impacts and the challenges those impacts create for faculty members.

Our TREE model encourages college and university leaders to prioritize diversity, equity and inclusion. Our goal is to get to the root of the problem of equity, rely on resources to provide the conditions for new growth and adapt our approaches to evaluation -- pruning those that do not serve us -- all with a goal to create strong and healthy faculty careers that are not blighted by the pandemic.

That means identifying how the pandemic has differentially affected faculty members who vary by gender, caregiving status, race, rank, field and even method of scholarship. It also means colleges and universities should provide faculty members with resources to manage the short-term impacts, reconsider how evaluations are conducted to address the long-term ones and create the conditions under which all faculty members can grow and flourish into the future.