You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

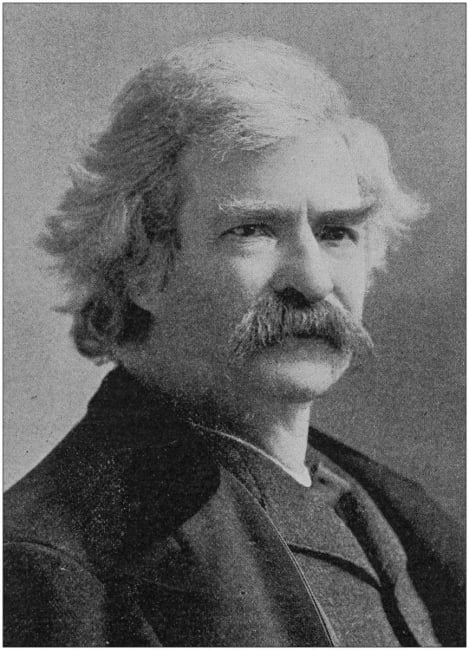

Mark Twain

ilbusca/istock/getty images plus

Persons reading this essay who are looking for an unqualified defense of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, its author or the language he uses will be disappointed, as will persons hoping to cancel Mark Twain and his fictional progeny.

Most Americans, many of whom have never read Mark Twain’s fiction, position him at one ideological extreme or another: either he’s a secular saint, the quintessential icon of wholesome, wisecracking, humanistic American values, or he’s an embodiment of white privilege, a white man in a white suit whose pleasure -- reflected in his love of racial caricature and racist vocabulary -- is an inverse measure of someone else’s pain. Both extremes traffic in the sorts of moral absolutes that Mark Twain found as dangerous as they are simplistic and regressive.

Instead of invoking false dichotomies, what we hope to accomplish here -- using Twain’s writing as just one example -- is to demonstrate how thoroughly American it is to wrestle with “critical race theory,” a phrase that Twain would have found as unwieldy as it is imprecise. Nonetheless, it is a concept that inspired his major works. In Pudd’nhead Wilson, the last of Twain’s novels set in the Mississippi Valley of his youth, Twain suggests that race is simply a “fiction of law and custom.” Yet in his earlier novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain made clear how dangerous that fiction can be, particularly to Black Americans. If Twain would at times lay bare the self-evident truth that all humans are created equal, he also revealed, particularly in the treatment of his Black characters, that “Human beings can be awful cruel to one another.”

Politicians and opposition groups are now targeting critical race theory as a disruptive narrative in American culture, casting it as newly conceived, the love child of MSNBC and the Black Lives Matter movement, designed only to create civic unrest and make white Americans uncomfortable. The truth is that trying to unravel the knot of race, racism and American history has been a central preoccupation of American culture since the first enslaved Black person was brought to these shores in 1619.

In almost every expression of American art, letters, music, politics and culture -- from Elvis’s “Blue Suede Shoes” to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, from the Federalist Papers of Alexander Hamilton to the Hamilton of Lin Manuel Miranda -- Americans are grappling with the nature of race and the scars of racism. The American habit of rationalizing oppression began well before the writing of the Declaration of Independence and continued to the beginning of the 20th century, when, in a speech given at the first Pan African Convention, W. E. B. Du Bois pronounced, “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.” Du Bois’s words have never rung truer than in today’s current skirmishes about the recasting and teaching of American history.

Mark Twain was American literature’s first critical race theorist as well as America’s greatest writer. His most famous work, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is a nihilistic satire about systematic racial and gender oppression, a rejection of sanctioned education and religion, and a searing metaphor for the failure of Reconstruction. But for over 130 years, no one got the joke, so to speak, or, if they did, their voices went unheard. Instead, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was turned into a comic book, a Disney riverboat ride, a movie vehicle for Mickey Rooney’s overacting and Ken Burns’s slow pan. The joke that Twain so artfully and ironically crafted was that America was a nation of freedom and equality where everyone had “unalienable rights.” And since Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’s publication in 1886, in addition to being one of the most frequently banned novels, it has been consistently and carefully misread by generations of scholars who, consciously or not, were collaborators in the whitewashing of American literature and history. Twain’s covert and disruptive meanings were as submerged as the wrecked steamboat Walter Scott, and his audience both then and now was inclined not to look beneath the surface of the muddy Mississippi.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been hijacked by contemporary, deliberately ahistorical and homogenized white American popular culture. This becomes even more obvious when you consider that the novel’s principal action begins with a little boy so terrified of his drunken and murderous father that he trains a shotgun on him while he sleeps, resolved to kill him if he awakens. To escape his father, Huck shoots and guts a pig to fake his own death and runs to the safety of the Mississippi river and Jim, Miss Watson’s fleeing slave. As Huck and Jim drift the wrong way down the Mississippi, they hear of a drowned, cross-dressed woman floating in the river (a runaway slave, per Ellen Craft), witness the generational gun violence of the Shepherdsons’ and Grangerfords’ feud, and encounter the menacing and bankrupt Duke and Dauphin. By novel’s end, when the next generation of the slave-holding, well-educated Southern gentleman, in the person of Tom Sawyer, shows up to re-imprison Jim as a bit of fun before admitting that he was freed two months earlier, Huck has had enough. Jim is not free, only “freed.” Huck, an orphan with little education and less religion, decides to exit this existential Hades and light out for “the Territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally, she's going to adopt me and sivilize me and I can’t stand it. I been there before.”

We react to the humor when reading Adventures of Huckleberry Finn because Twain was a brilliant satirist and that’s what satire allows us to do -- to laugh at the unlaughable. This was a hard novel for Twain to write. He was the son of parents who owned slaves, and he briefly served as a Confederate soldier in the Marion Rangers. (He later satirized his service, saying he deserted after a few weeks because he grew tired of retreating.) Twain wrote the novel over seven years in three periods, 1876 (toward the end of Reconstruction), 1880 (three years after President Rutherford B. Hayes pulled federal troops out of the South) and 1883 (a year after his return to Hannibal and the Deep South). During those years, political and legal protections for Black people were dismantled, and lynchings became a form of public entertainment. Twain would go on to write The United States of Lyncherdom in 1901, an essay that would not be published until 1923: “Lynching has reached Colorado, it has reached California, it has reached Indiana -- and now Missouri! I may live to see a negro burned in Union Square, New York, with 50,000 people present, and not a sheriff visible, not a governor, not a constable, not a colonel, not a clergyman, not a law-and-order representative of any sort.”

Twain also supported the concept of reparations, providing financial assistance to Warner T. McGuinn, one of Yale University’s first Black law students, and to Charles E. Porter, a Black painter who specialized in still-life painting and was living in Paris. In 1906, he shared the stage with Booker T. Washington at Carnegie Hall to raise funds at a sold-out benefit for the Tuskegee Institute. Like many Americans today, Twain struggled to do -- as Spike Lee might have it -- the right thing, while also occasionally choosing to do the easy thing. He chose not to publish The United States of Lyncherdom, feeling that the country and, more to the point, his readership was not ready to hear the truth.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn reflects these same conflicted impulses, although in its fraught conclusion, Twain resists the pressure he must have felt to sell us a happy ending. Generations of scholars have written that they were disappointed with the ending of the novel, describing it as “a thematic dead end, full of ‘flimsy contrivances,’” and that the characters of Huck, Jim and Tom were demeaned or reduced with the pretend re-enslavement.

Yet they all missed the joke. Critics and the public demanded a happy ending, but Twain refused to provide it, because there was none. So, in good American fashion, there was a gentlemanly “Homer nods” agreement, and American culture tacked on its own ending through movies and comic books and, in an infamous failed experiment a decade ago, editing and publishing a sanitized version of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with racial epithets removed -- in effect continuing the whitewashing of the past century and promoting the misguided concept that art is fungible.

The tragic truth that Twain satirized in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was that there was no safe place for Huck or Jim. Huck’s alternative solution -- abandoning civilization -- was doomed, and the novel’s ending violated an American expectation of happy closure. In writing a satire about the failure of Reconstruction, Twain proved that it was only through fiction that the truth about American racism, brutality and systemized inequity could be revealed. Regarding the teaching of American history, Twain should have the last say: “A historian who would convey the truth must lie. Often he must enlarge the truth by diameters, otherwise his reader would not be able to see it.”