You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The student center at the University of California, Riverside.

Jim Feliciano/iStock/Getty Images Plus

It’s not enough to be a Hispanic-serving institution anymore. There are now 569 HSIs, defined by the federal government as institutions where Hispanic students account for at least 25 percent of undergraduate enrollment. It’s time for a further distinction that acknowledges the universities that not only enroll large numbers of Latino students but do more to intentionally serve them.

It’s time for the super HSI.

The super HSI is intentional in its approach to students, measures and demonstrates outcomes, commits an identifiable investment in Latino students, and seeks to strengthen relationships with the Latino community, inside and outside the university.

Recently, several organizations have called attention to the difference between serving and enrolling Latino students. Excelencia in Education stepped forward to acknowledge universities that transcend the standards required to become an HSI. It created the Seal of Excelencia, a certification for institutions that are intentional in their support of Latino students. Additionally, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has funded Crossing Latinidades, a project involving 16 HSIs and doctoral universities with Research 1 status that are collaborating to further develop Latino studies across the humanities. And the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs has identified 35 HSIs as Fulbright HSI leaders for their strong engagement with the U.S. government’s flagship global exchange program over the years. The University of California, Riverside, was one of just five institutions acknowledged by all three programs.

Stephanie Aguilar-Smith’s published study “Seeking to Serve or $erve? Hispanic-Serving Institutions’ Race-Evasive Pursuit of Racialized Funding” discusses the differences in how universities regard the HSI designation. Aguilar-Smith’s interviews with administrators, staff members and professors revealed that some colleges apply for HSI grants to offset budget shortfalls or fund general university projects.

These institutions assert that any investment in the institution will ultimately help Latino students. But this argument is lacking in a fundamental appreciation for the value of Latino student support services.

Perhaps we’ve got the threshold for what constitutes an HSI wrong. In California, for example, where 39.4 percent of the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, the 25 percent enrollment hurdle that qualifies an institution as HSI doesn’t come close to providing equitable representation.

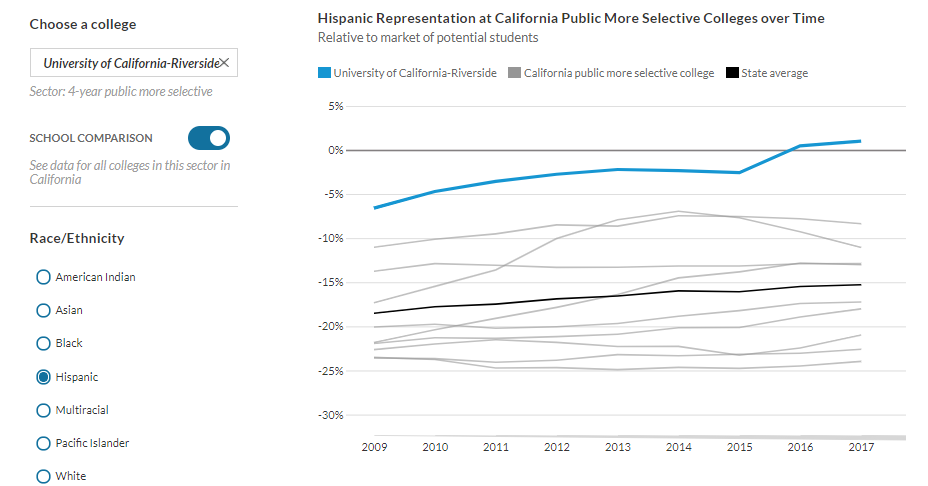

A truer qualifier would be graduating all students at equivalent rates after enrolling Latino students in proportion to the local population of potential college students. UC Riverside, where I serve as chancellor, far outperforms other “more selective” public universities in the state on this measure and is the only more selective public university in California to enroll Hispanic students in excess of their representation in the potential student market, based on study findings in the Urban Institute report “Racial and Ethnic Representation in Postsecondary Education.”

A truer qualifier would be graduating all students at equivalent rates after enrolling Latino students in proportion to the local population of potential college students. UC Riverside, where I serve as chancellor, far outperforms other “more selective” public universities in the state on this measure and is the only more selective public university in California to enroll Hispanic students in excess of their representation in the potential student market, based on study findings in the Urban Institute report “Racial and Ethnic Representation in Postsecondary Education.”

Over all, across the nation, the Urban Institute report found that Hispanic students are underrepresented at more selective universities by nine percentage points. Given the number of universities in areas with heavily Latino populations, this shouldn’t be the case.

The best Hispanic-serving institutions exhibit a commitment to Latino students that transcends numbers. At Riverside, we have long been committed to a culture centered around student success across demographic lines, and we recruit people—faculty and staff—who align with our values. Then we develop programs based on expressed student needs, tracking performance as well as the evolution of those needs.

Our “culture-people-programs” model has been a part of our university DNA and commitment to Latino students since long before I arrived on campus. It goes back to even before the 1979–1984 tenure of UC Riverside chancellor Tomás Rivera, the UC system’s first Mexican American chancellor, for whom our main library is named.

In 1972, our Chicano Student Programs department was established; it will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year. In its early days, the department was focused on college access, with students often doing the work of educating their communities about the university. Today, CSP provides academic and social support to Latino students with programs like peer mentoring, alumni networking and a living-learning residential community called Mundo.

Our Chicano Link Peer Mentor program pairs first-year, transfer and graduate students with more experienced students, offering a chance for those new to the university to gain support in navigating the campus as well as to alleviate any fears or uncertainties they may have. Mentors recognize mentee strengths and offer solutions for overcoming challenges.

In addition to improving the higher education experience for its participants, the mentor program has been correlated with higher retention and graduation rates. For the 2015 cohort of first-time, full-time Latinx students, four-year graduation rates were 14 percent higher than for those who did not participate in the program.

The “culture-people-programs” approach goes beyond enrollment to help Latino students thrive in their academic and postgraduate lives—and not just at Riverside. Peer institutions like University of Central Florida have also developed programs to support Latino student success.

At UCF, the LEAD Scholars Academy is a selective and comprehensive leadership development program that includes the study of leadership principles, a living-learning community and service-learning classes. As might be expected, LEAD scholars have higher graduation rates than the general population of students.

But to further serve Latino students, UCF added a Latino leadership track that includes a Latino leadership framework, service learning opportunities in the Latino community and study of Latino current events. Program retention rates affirmed that Latino students engaged in high-impact practices and culturally responsive curricula are more likely to be retained.

Understanding that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been financially devastating to some colleges and universities, one might argue that the threat of closure at any institution enrolling Latino students hurts the Latino population. Bailouts and acquisitions may be necessary to help struggling institutions through what has been a challenging time.

But HSIs should be called upon to demonstrate how they are scaling their efforts to effectively serve Latino students in order to access the funds intended to support a population that has traditionally been underserved. The government funding should be funneled to those institutions that more intentionally serve Latino students—the super HSIs.