You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Wikimedia Commons

Sometimes the ethical issue is determining whether you actually have an ethical issue. Is what I’m feeling moral outrage or mere irritation? Is the issue in question worth pursuing? Where is the line between standing up for principle and tilting at windmills? How do you know when you are a voice in the wilderness and not just a windbag?

Recently I received a request to supply data for a survey my high school is required to submit annually to the governing body that oversees us and five other Virginia schools. Complying with such requests for data is one of the least favorite parts of my job, and this one in particular always produces a visceral reaction in me best described by the verb “groaned.”

This year I was actually relieved to see the survey. A week before I had a conversation with a colleague responsible for the narrative portion of the report. When I asked about the data collection piece, she responded that she had never seen the information asked for and looked at me like I was crazy. It turned out that the data collection is handled by another office on campus.

My part of the report is very small, encompassing one data point, so I know I have no reason to complain. That doesn’t stop me, of course, nor does the recognition that my colleagues on the college side are burdened far more often with such requests. I rationalize that with the argument that there is no high school version of the Common Data Set. I may be naively (and falsely) assuming that the existence of the Common Data Set has simplified how colleges respond to requests for random data, and if so I apologize to my college admissions colleagues and institutional researchers who are responsible for doing so.

The survey in question and I have a history, a history best described as a test of wills. The data I am asked to report has to do with SAT scores for our senior and junior classes, and what I have always been asked to report is average SAT scores.

As a member of the National Association for College Admission Counseling and a past president of that organization, I believe in and agree to support the Statement of Principles of Good Practice. One of the components of the SPGP, listed as a best practice but not a mandatory practice, is that institutions should report out test scores not as mean scores but rather as a middle 50 percent range. So every year when asked by my business office for the mean scores so they could include in the report, I would dutifully respond that the ethical standards for the college admission profession did not allow me to report mean scores and I would provide a middle 50 percent range instead.

I don’t know what transpired from that point. For all I know the business office staff may have taken the middle figure of the middle 50 percent range and used that as an average the first couple of years, but eventually they got tired of my standing on my middle 50 percent soapbox and dutifully reported the range as well as my philosophical objection to average scores in the report each fall. And the following year the report would come back asking for average scores once again.

The older I get, the preachier I become. Two years ago, during the same week I received two different surveys, both of which asked for average SAT scores, and I was moved to be more aggressive in stating my ethical objections. The other survey was from a consortium of schools that have banded together to provide online courses, and it wanted to put together a profile doument, including student mean SAT scores. I contacted them to point out the best practice against citing mean scores, and they subsequently decided not to include student scores as part of the profile.

Emboldened by my success with that survey, I wrote to the head of our governing body when the annual survey came out, once again asking for average SAT scores. I pointed that the SPGP stated that institutions should report scores using the middle 50 percent range and that the use of average or mean scores was not appropriate.

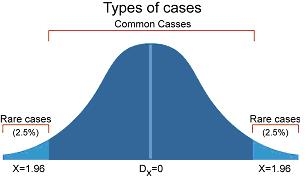

The head and I went back and forth. He argued that the middle 50 percent was about reporting to outside groups but that reporting to governing boards was different, and questioned why the use of average scores would be unethical. My answer was that the middle 50 percent range is not about who received the scores, but about the validity of the data point itself. The use of mean or average scores at best gives authority and precision to something that even the College Board in unguarded moments admits is not precise (30 point margin of error per section), and at worst may even constitute worshipping a false god (with a small “g”).

The head of the governing body was skeptical of my arguments, but wanted to do the right thing. I therefore reached out to colleagues around the country looking for data or research to support the validity of using the middle 50 percent. My initial post on a couple of discussion boards received vehement support but little research, so I turned to David Hawkins at NACAC, my go-to source for historical context on admission policies.

David pointed out that use of the middle 50 percent range is not something that originated with NACAC but has its origins in the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing, in which a comment on Standard 13.19 observes that reports that go beyond average score comparisons support thoughtful use and interpretation of test scores. Use of the middle 50 percent range has become the industry standard. The College Board advises institutions that use of the middle 50 percent range provides students and counselors with a more accurate picture of what an individual score might mean, and both the Common Data Set and the U.S. Department of Education ask for middle 50 percent range in reporting scores.

And now my school’s governing body does as well. When this year’s survey came out, it asked not for average scores but for the middle 50 percent. The irony, of course, is that the successor document to the SPGP, the Code of Ethics and Professional Practice, contains no mention of the middle 50 percent. That’s not because it’s no longer valid, but because the new document includes only mandatory principles.

I’m not sure whether that counts as a victory for the forces of ethical college admissions. Each of us encounters ethical dilemmas every day, and not all of them are momentous. But ethics means living one’s ideals in moments both large and small.