You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Wikipedia

Last week I learned that the farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland once owned by my grandparents is for sale. It’s been years since I’ve seen it, and the house and outbuildings were long ago torn down, but the news brought back memories.

When I was growing up, the only vacations my family took were visits to the farm. I’m sure I missed out on seeing the glamorous places that wealthier and more adventurous families experienced, but there were other rewards -- lots of land to explore, eating strawberries off the vine and going crabbing on the nearby Wye River.

The visits to my grandparents also expanded my cultural horizons, exposing me to two televised sporting events not available at home. One was professional wrestling. My grandfather was a true believer, but even at the age of 9 I was suspicious that Gorilla Monsoon was not someone’s real name.

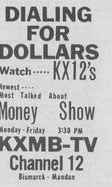

The other was Duckpins for Dollars, a Baltimore spinoff of Dialing for Dollars. On Duckpins for Dollars, a contestant, seemingly always from Dundalk or Arbutus, would try to win money for a partner at home by bowling a strike, not easy to do in duckpins.

This is the time of year when college admission has its own version of Dialing for Dollars, as families contact colleges hoping to negotiate a sweetened financial aid package.

Last week a father called me asking about negotiating aid. His child had received acceptances with scholarships at two good colleges, but no scholarship from the two colleges where the student was most interested. The father was skeptical of the value of calling the college to reconsider, but his wife had heard definitively from other mothers that everyone negotiates for aid.

“Everyone is doing it!” Most of us are able to resist that line of reasoning when it comes from our children haggling for a later curfew or some other rite (or right) of passage. So why do we fall for it when it comes from our peers and involves the college admissions process?

We fall for it for the same reason we fall for so many “suburban legends,” the beliefs or myths that people accept uncritically about the college admissions process. Suburban legends are the things that parents discuss in the grocery store, on the sidelines of games and at social gatherings. They always sound plausible, but they never happen to anyone you actually know but rather to a FOAF (friend of a friend), or more commonly, the best friend of the girlfriend of the son of a third cousin’s co-worker.

Suburban legends are less about everyone doing it than someone doing it successfully. That plays into parental fear that there is some secret to college admission everyone else knows about but has escaped us. That fear will only increase in the wake of the Operation Varsity Blues scandal.

Is everyone haggling for financial aid? And is haggling kosher?

I suspect this may be another example of things about college admission that are in flux, where there is a disconnect between our ideals and the realities. Once upon a time, it would have been considered uncouth to haggle over price. That was back in the days when higher education pretended that it wasn’t a business.

Today, however, there is no question that college choice is at least partly driven by economics, given how few of us can write a check for tuition without heart palpitations. Colleges employ consultants who use sophisticated algorithms to determine what combination of price points will maximize revenue, and financial need is less important than willingness to pay. There is also evidence to indicate that negotiating is more common and more likely to work. A 2014 New York Times article reported that many private colleges give additional aid to more than half the families who appeal, and another Times article from 2017 described financial aid appeals as an “annual ritual,” even going so far to suggest that families consider hiring a professional haggler.

Is it worth asking for more aid? The answer is the same as to every question related to college admission: “It depends.”

I asked the father for more detail about the scholarship offers on the table. Were they part of a need-based financial aid package or were they “merit” scholarships? Jon Boeckenstedt of DePaul University has argued persuasively that need versus merit is no longer a meaningful distinction, that almost all aid involves some form of tuition discounting. In this case I think the distinction is relevant, although that may reveal my naïveté or profound misinformation.

If the discrepancy between two colleges’ financial packages is due to differing analysis of a family’s ability to pay, then that would be a reason to request reconsideration from the institution making the less generous offer. There is no guarantee they will change the package, but you have in writing a more favorable need analysis.

What about a case where a family’s financial resources have changed dramatically since the “prior-prior” year used to analyze need on the Free Application for Federal Student Aid? If there is new information, it is worth communicating with the financial aid office, but my experience is that the response will be that the dramatic change in circumstances will be caught the following year. Chris Gruber at Davidson has also observed that families never call at this time of year to report that their finances are so much better that they no longer need quite as generous an aid package as they received.

As I expected, in this case the scholarships were merit based and came from two colleges where the student was in the upper part of the applicant pool. The scholarships were an attempt to entice a student to enroll who might not otherwise consider that college as an option. The other two universities were places where the student was fortunate to be admitted. In that case the student has less “merit,” and the colleges in question are likely to make their enrollment goal, so less likely to award more aid.

Are colleges more likely to be willing to negotiate aid offers the closer they get to May 1, just as car buyers get better deals at the end of the month when salespeople and dealerships have quotas to hit? The answer, once again, is “it depends.”

If the college in question is worried about making its class and the student falls in the top part of the applicant pool, perhaps. Certainly a tactic used by some colleges that have failed to reach their enrollment goals on May 1 is to offer more aid as an enticement, but that’s unethical unless the student has initiated the conversation. But one of the New York Times articles suggested that more aid becomes available close to May 1 as other applicants turn down packages to attend other institutions. I don’t think that’s how financial aid works.

I generally discourage families from trying to negotiate for aid, with one exception. If there is a college that is a clear first choice and finances are an impediment, I would want the college know that, understanding that it may be unable or unwilling to sweeten the aid offer.

If that doesn’t work, don’t sell the farm (especially if you don’t own one) and don’t buy the suburban legend that everyone is successfully negotiating for aid.