You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

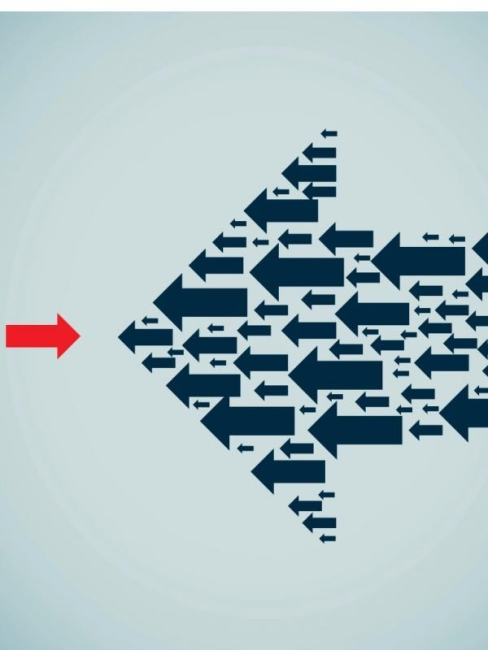

Istockphoto.com/erhui1979

Since defending my dissertation in 2013, I have worn several hats at the University of Michigan. As a result, I am contacted occasionally by graduate students who are considering multiple career options and want to sit down for an informational interview -- a casual conversation with a professional about their career trajectory and the nature of their current work or industry.

How exactly does one transition from researching immune responses during African trypanosome infection to implementing professional development programming for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars? Although I can say with all authenticity that each role that I have held at the university afforded me a new skill set that I was able to carry with me, apply to future positions and weave into a cohesive story on a résumé, the truth is that the process was messier than it looks.

I think this messiness is helpful to share with graduate students and postdocs because it alleviates some anxiety that they have to have it all figured out from day one in their program. That said, after reflecting on these past six years, I’ve realized that if I had been a bit more intentional while in graduate school, it might have helped me more quickly identify the aspects of my work that I find truly fulfilling.

One of the positions that I held prior to joining the graduate school was that of instructional consultant at the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching at the university. I often sat with instructors who would ask how to structure a course, and I would start by asking them about their learning goals or objectives. If they were unable to answer that question, it was my opportunity to explain the concept of backward design. (For those who would like the full explanation of this concept, you can read the book Understanding by Design by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. The Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching also has a nice, succinct description on its website.)

In a nutshell, backward design tells you to start with the end in mind. Many instructors plan for the semester by selecting readings, then designing activities and homework, and finally working on crafting exams or other large assessments. Backward design tells you to do exactly the opposite: start with the overarching course or learning goals, determine how you will know students have met these goals and then craft readings, activities and the like. Restructuring courses in this way has been truly transformative for select instructors with whom I’ve worked in the past, and I find myself applying the framework regularly when designing workshops and other programs.

So what does this mean for you as a graduate student or postdoctoral scholar? Let’s walk through the steps in a bit more depth.

Identify desired results. Wherever you are in your studies or research, take a step back and think about what your goals are. For the longer term, it might be helpful to reflect on your core values, which you can read more about here. Some open-ended questions that you might ask yourself are, “What kinds of career paths align with my interests and values?” and “What kind of work makes me feel the most energized?”

Does this mean you have to have everything figured out? Absolutely not. In the short term, perhaps a desired result is that you leave graduate school having demonstrated your ability to communicate your research effectively. As we’ll explore further, that does not lock you into a single path, but it provides some structure for your professional development.

Determine acceptable evidence. When I met with instructors in my previous role, this generally led to a discussion about assessment. How do you actually measure whether or not students are learning what you want them to be learning? To apply this to your career exploration, ask yourself, “How will I know that I’ve successfully met my desired outcome(s)?”

In our example of effectively communicating your research, maybe acceptable evidence to you is that you present your work during at least one disciplinary conference during your time in graduate school. To one of your colleagues, it might mean that they are able to clearly explain their research to a lay audience. Although you both have the same desired result, what you articulate as acceptable evidence is completely different, which allows you to individually tailor the process.

Plan learning experiences. Now that you have identified results and figured out how you’ll know when you’ve been successful, you can craft activities and learning opportunities accordingly. Ask yourself, “What is one concrete and actionable step that will get me closer to this outcome?”

Continuing with our same hypothetical example, perhaps your next step is to schedule a meeting with your adviser to discuss which disciplinary conference is appropriate for submitting an abstract. You might also do some research to see what opportunities are available through your department or graduate school to brush up on your presentation skills, such as those listed on the UM Rackham Graduate School’s webpage on the core skill of communication.

Your friend might instead decide to apply to the Catalyzing Advocacy for Science and Engineering workshop through the American Association for the Advancement of Science (more information here) so that they can learn about articulating the importance of their research as it relates to science policy. Again, the paths that you select are completely different, but they both point back to the same desired result.

You should also keep in mind that this is an iterative process. What if you take advantage of the opportunity to present at a conference, but upon reflecting on your presentation, you feel like you stumbled when answering questions from the audience? That might cause you to set a new desired outcome to become more proficient with improvisational speaking. You could make a plan to engage in some improv activities, connect with a local Toastmasters International club or volunteer for a poster session where you will be asked unpredictable questions about your research. Reflecting on the evidence that you gather can help you refine your goals and direction.

As I was outlining this piece, I smiled when I realized that these steps spell out the initialism “IDP.” In the career and professional development world, IDP also stands for individual development plan, which in its broadest sense is a tool to identify and make steps toward one’s career and professional development goals. If you have not already done so, I strongly recommend that you explore some of the structured tools available for this purpose. For those in STEM fields, I would point you to myIDP, which is an excellent online tool tailored to graduate students and postdoctoral scholars in the sciences. For scholars in the humanities and social sciences, I would direct you to ImaginePhD, which was developed through the Graduate Career Consortium. Both will give you the opportunity to reflect on your skills, interests and values so that you can create SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound) related to your career and professional development. You can read more about systematic career exploration in Rebekah Layton’s excellent "Carpe Careers" piece.

In most informational interviews, I find myself encouraging graduate students and postdocs to think about career and professional development early and often, as is described in this post. That said, it is never too late! In another "Carpe Careers" piece, Chris Golde describes the helpful metaphor of looking at a career as chapters that add up to a book. Backward designing your career does not mean that your path will be perfectly streamlined or that your book will be only one chapter. In fact, that should not be the goal, as your needs and interests will continue to shift throughout your life, and you will find yourself taking on new challenges and stretching yourself in different ways.

Reflecting back on my own graduate school experience, I was not aware of the majority of career options open to me, and if I could go back and do one thing differently, I would have sat down with a career counselor to talk through the possibilities. My hope for those of you reading this piece is that by taking the time to think about your desired outcomes early in your career, you will save yourself time and make space to write rich chapters that add up to a fulfilling career and life story.