You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Part 7 of my Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2012 series

I chose “data” as one of the top trends of 2011, and the opening line of that article reads “If data was an important trend for 2011, I predict it will be even more so in 2012.” Indeed. There’s a great deal that happened in 2012 that’s a continuation of what we saw last year — enough that I could probably just copy-and-paste from the article I wrote back then:

More of our activities involve computers and the Internet, whether it’s for work, for school, or for personal purposes. Thus, our interactions and transactions can be tracked. As we click, we leave behind a trail of data–something that’s been dubbed “data exhaust.” It’s information that’s ripe for mining and analysis, and thanks to new technology tools, we can do so in real time and at a massive, Web scale.

There’s incredible potential for data analytics to impact education. We already collect a significant amount of data about school and students (attendance, demographics, test scores, free and reduced lunches, and the like), but much of it is administrative and/or siloed and/or unexamined.

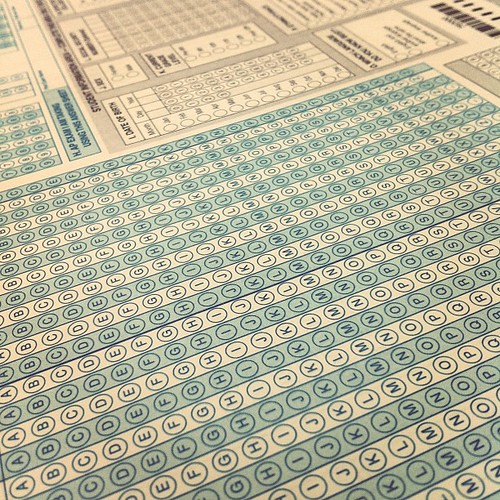

…Despite the promise of personalized learning through analytics and data, what we’ve actually seen this year is an increasing emphasis on standardization (or rather, standardized testing). And as such, most of the stories about education data this year have been stories about testing. Stories about dismal test scores. Stores about teachers’ performance tied to those student test scores. Stories about cheating.

It’s no wonder that talk about “data” (or its variation “data-driven”) continues to make lots of folks shudder.

What Counts as “Education Data”?

”It would be nice if all of the data which sociologists require could be enumerated because then we could run them through IBM machines and draw charts as the economists do. However, not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” – William Bruce Cameron (1963)

But what do we mean by “education data”? And do we risk, as the Cameron quote (often attributed to Einstein) suggests, valuing the wrong thing by focusing on certain data and certain measurements?

“Education data” is more than just standardized test scores, of course (but if you’re keeping track at home, SAT scores were down this year and the ACT scores remained flat). For some other interesting education data from the year, we can look at U.S. poverty rates (up) or median household income (down); how much states in fact spend on standardized testing; how much for-profit schools spend on advertising; the impact of iPads on literacy among Maine’s kindergarteners; the state of wiki usage in K–12 schools; online forum usage in higher ed; how much is invested in ed-tech startups; high school graduation rates; employment rates for college grads; where the Gates Foundation spends its money; how many teens own smartphones (55.5%); crime rates in schools (down); youth suicide rates (up); the enrollment of special education students at charter schools; the metadata on the Harvard University Libraries collections; demographics of MOOC enrollees; the confidence on public schools (an all time low); who has student loan debt and how much; how much adjunct faculty earn; how well students perform in virtual schools; and how the physics of Angry Birds works (and what you can learn from it).

What can you learn from it — from all this data? Great question — one that many journalists, politicians, entrepreneurs, government officials, researchers, and others have sought to answer this year. The promise of this data they argue is that through mining and modeling, we can enhance student learning and predict student success.

The Politics of Education Data

“Data, data everywhere and not a drop to drink” – The Rime of the Ancient Psychometrician

The Department of Education pushed that promise of “big data” in a big way this year. In April, it issued a draft report on data mining and learning analytics that tried to make the case for how these practices will transform education. (The final version of the report was released in October.)

The department’s interest in data and analytics are connected to a number of other key initiatives, including the 2010 National Education Technology Plan and the Obama Administration’s funding competition Race to the Top (RTTT). The latter demanded states and districts conform to a number of data-oriented reforms, including “supporting data systems that inform decisions and improve instruction, by fully implementing a statewide longitudinal data system, assessing and using data to drive instruction, and making data more accessible to key stakeholders.”

Of course, RTTT emphasizes data in other ways too — namely, more standardized testing, and in turn, then using that data to assess teachers. Once again, we’re back to just thinking that the education data that “counts” are test scores. And as in 2011, this became highly politicized when teachers’ names and associated test score data were made public.

In February, following a lengthy legal battle, the city of New York released data about almost 18,000 individual math and English teachers’ performance. The Teacher Data Reports ranked teachers based on their students’ gains on the state’s math and English tests over the course of 5 years (up until the 2009–2010 academic year).

Also known as “value-added assessment,” the data is purported to demonstrate how much a teacher “adds value,” if you will, to students’ academic gains. By looking at students’ previous scores, researchers have developed a model that predicts how much improvement is expected over the course of a school year. Whether students perform better or worse than expected is then tied to the impact that a particular teacher had.

Proponents of value-added assessment — that includes Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and former NYC School Chancellor (and now head of News Corp’s education division) Joel Klein — argue that this model demonstrates teachers’ effectiveness, and as such should be used to help determine how to compensate teachers, as well as who to fire.

While the teacher’s union and teachers have been vocal in their opposition to the city’s move to release this data, they aren’t the only ones deeply skeptical and deeply troubled by this particular measurement — let alone the appearance of individual teachers’ names and rankings in local newspapers. Arguing that “shame is not the solution,” even ed-reformer Bill Gates penned an op-ed in The New York Times arguing the release of the Teacher Data Reports was a bad idea.

In no small part, that’s because there are many problems with relying on value-added assessments to determine a teacher’s effectiveness. First and foremost, of course, it reduces the impact that a teacher has on a student to a question of standardized test scores. How does a teacher help boost a student’s confidence, critical thinking, inquisitiveness, creativity? What about other subjects other than math or English? What about teachers whose students are gifted, have disabilities or are still learning English? (Well, according to VAM, they’re “bad teachers.” The “worst” math teacher in NYC, in fact, had many students who received perfect scores — but as these students hadn’t improved from previously stellar scores, well…) What about poverty and other socio-economic influences on students’ lives?

Furthermore, there is a sizable margin of error in these value-added assessments. As The New York Times notes, the scores could be off as much as 54 to 100 points, and the city is only “95 percent sure a ranking is accurate.” As Gotham Schools reported several years ago, the margin of error has meant that “31 percent of English teachers who ranked in the bottom quintile of teachers in 2007 had jumped to one of the top two quintile by 2008. About 23 percent of math teachers made the same jump.” Did these teachers suddenly get better? We just don’t know.

The Business of Education Data and Learning Analytics

Not knowing hasn’t stopped us from assessing, measuring, monitoring, and mining, (and from condemning, damning, and dismissing teachers). Nor has it stopped the testing industry from expanding and profiting — something that will continue to occur with the new Common Core State Standards and their associated testing requirements. (According to a recently released study by the Brookings Institute, the states spend about $1.7 billion per year on testing in K–12.)

But a ridiculously impossible question about pineapples and hares on the (Pearson-developed) New York State eighth grade language arts exam — one where based on a wonderfully absurdist story by children’s author Daniel Pinkwater and one where every multiple choice answer was equally right or wrong — helped draw attention to the problems of these tests’ design and usage. (You can read the passage and the test questions here.)

“Pineapples don’t have sleeves.” — New York State 8th Grade ELA Exam

Nevertheless big data was big business in 2012, and lots of companies released data and analytics products, including:

Shared Learning Collaborative: This Gates Foundation-funded initiative was best explained this year by Frank Calatano who used “buckets” and “spigots” to describe the SLC’s infrastructure plans: K–12 data stores, APIs, and Learning Registry-related content tags. (More to come on the SLC in my next Top Ed-Tech Trends post.)

Learnsprout: A graduate of the ImagineK12 program, Learnsprout is API-focused startup helping schools integrate other products with their SISes. It raised $1 million funding from Andreessen Horowitz and participated in Code for America this year. (I wrote about the startup here; more to come.)

Clever: Backed by Y Combinator, Clever also launched this year with an API-oriented solution to the problems of SIS data siloes. It raised $3 million funding from Ashton Kutcher, Mitch Kapor, and others. (More to come on Clever.)

Kaggle: The data mining/machine learning competition site Kaggle hosted several education-related contests, including a Hewlett Foundation-sponsored one on automated essay grading (yes, more to come on that.) Kaggle also hosts “Kaggle in Class,” which allows the data mining platform to be used in class-based assignments/contests.

Amplify/Wireless Generation: Rupert Murdoch’s plans for his company’s education division got a little clearer this year with the unveiling of Amplify in June. News Corp had acquired Wireless Generation and had hired former NYC Schools Chancelor Joel Klein in late 2010. Much of the focus of Amplify remains on what were Wireless Generation’s offerings: assesment and analytics. For its part, Wireless Generation remained involved in the development of the Shared Learning Collaborative; and it won a contract to build a Common Core State Standards assessment reporting system.

Kickboard: From New Orleans founded by TFA alum Jen Medbery comes Kickboard, which gives schools and/or teachers a way to track academic and behavioral data, along with family contact, in one dashboard. (I covered Kickboard here.)

Always Prepped: Another data dashboard for teachers, Always Prepped raised $650,000 in seed funding from True Ventures in November.

TeachBoost: Another ImagineK12 alum, TeachBoost offers a school to track teacher’s performance data, from classroom observations and evaluations. (I covered TeachBoost here).

Academia.edu: In August, the “social network for scholars” Academia.edu launched an analytics dashboard so that users could track the citations of their research in real-time.

Coursesmart: The largest digital textbook provider, Coursesmart recently launched an analytics tool that tracks a student’s usage of an e-book, including page views, time spent in the app, highlights made, notes taken — then notifies the professor of that student’s “engagement score."

IBM/Desire to Learn: In April, IBM and Desire2Learn announced a partnership for their Smarter Education Solution — one part D2L LMS and one part IBM analytics. Desire2Learn raised $80 million — its first VC investment — this year.

Instructure: In June the LMS startup Instructure unveiled its analytics feature. With it, students can view their assignments, grades, and other performances stats, and they can see how they’re doing compared to others. Instructors can see overviews of courses, compare courses, and (ideally at least) identify and help struggling students.

Coursera: The online education startup Coursera announced just last week its plans for Coursera Career Services, whereby students (via performance and geographical data) would be matched with potential employers (See also: MOOCs.)

Udacity: Udacity also offers a similar recruiting service to employers based on students’ data (See also: MOOCs.)

Civitas Learning: Founded by Charles Thornburgh, a former exec at Kaplan, Civitas Learning launched a predictive analytics platform to help colleges and universities identify “at-risk” students. The company raised $4.1 million in funding this year.

Junyo: 2012 wasn’t such a good year for Zynga… errr, former Zynga exec Steve Schoettler’s learning analytics startup Junyo, according to Edsurge, which reported on its pivot in September.

Knewton: Arguably Knewton remains the company most synonymous with education data and analytics. Early in the year Fast Company named it one of the world’s most innovative companies.

Whose Data Is It Anyway?

“Data is the new oil” — Marketers, everywhere

We often hear that "big data is big oil," but the metaphor's a lousy one, Jer Thorp (Data Artist in Residence at The New York Times) recently argued, admitting that possibly the “idea can foster some much-needed criticality.”

Our experience with oil has been fraught; fortunes made have been balanced with dwindling resources, bloody mercenary conflicts, and a terrifying climate crisis. If we are indeed making the first steps into economic terrain that will be as transformative (and possibly as risky) as that of the petroleum industry, foresight will be key. We have already seen “data spills” happen (when large amounts of personal data are inadvertently leaked). Will it be much longer until we see dangerous data drilling practices? Or until we start to see long term effects from “data pollution”?

What happens when we use the resource extraction metaphor? How does that shape how we view (education) data? Indeed, as Thorp writes, “where oil is composed of the compressed bodies of long-dead micro-organisms, this personal data is made from the compressed fragments of our personal lives. It is a dense condensate of our human experience.”

Who owns the learning experience? Who owns all this education data? Companies? Schools? Instructors? Students? Do students know what data is being collected about them?

How can we make sure that learning analytics and data mining aren’t about extracting value but adding value? How do we make sure that in our rush to uncover insights from all this education data we now capture, that the student isn’t just the object of analysis? How do we make sure the student has subjectivity, agency and control — over their data and their learning?

To that end, the Department of Education did launch a MyData initiative this spring (which I covered in April). Much like the Blue Button that allows veterans to access and download their personal medical records from the VA in both human- and machine-readable formats, a MyData button will allow students to download and store (and share as they choose) their personal educational records.

Of course, education data is a lot more complex and distributed. Unlike veterans’ data, which is centralized under the VA and Department of Defense, educational data is scattered across the federal, state, and local levels. (The Department of Education only handles financial aid data; it doesn’t control our transcript or test data, for example). Education data, as I argue at the beginning of this post, can include all sorts of other things too outside the realm of official institutions: what you read, who you are connected to via social networks, what videos you’ve watched, what you’ve built and written and accomplished.

The MyData button, along with personal data lockers, could be seen as part of the growing “quantified self” movement, which involves collecting and tracking one’s own data through hardware (e.g. sensors like Fitbit), software (e.g. time-tracking tools like Chrometa), and/or handwritten journals and log entries. When applied to learning, there's the possibility then to construct one's own dashboards and visualizations.

As I wrote in a post on the quantified self and learning analytics back in April,

My concerns – and maybe “concern” is too strong a word – about the quantified self and learning involve a fixation about transactional data, about the easily quantifiable but in the end meaningless. There are a lot of obvious numbers in our day-to-day lives – what we read, where we click, what we like, how much time we spend studying, who we talk to and ask for help. It’s the administrivia of education. And frankly that seems to be the focus of a lot of “what counts” in learning analytics. But does this really help us uncover, let alone diagnose or augment learning? What needs to happen to spur collection and reflection over our data so we can do a better job of this – not for the sake of the institution, but for the sake of the individual?

One of the year's most important developments around the personal ownership of learning data might be the University of Mary Washington’s Domain of One’s Own project. The pilot offered some 400 students and faculty at the university their own domain name and Web space and helped them learn how to build their own e-portfolio — the power to control their data, even after they graduate.

As UMW’s Jim Groom writes, the Domain of One’s Own is

a conceptual shift in how we think about controlling data, syndicating content, aggregating ideas, and, more importantly for UMW’s purposes, empowering faculty and students alike.

There’s no one easy way to frame this project as an elevator pitch because it’s a very small, experimental instantiation of a much larger vision of Jon Udell’s that pushes us to imagine highly personalized digital domains wherein we manage myriad elements of our online lives from school work to personal photos to dental records to electric bills. A private/public domain of personal data that tells the stories of our lives and as a result is crucial for us to control and decide who sees what and what goes where. A digital social security number of sorts, a token that is secure and frames a context digitally that was heretofore not only been unnecessary, but unimaginable.

And that’s a vision for our personal learning data that looks quite different from a lot of the data dashboards and analytics tools that many companies and organizations want to sell us.

Image credits: CIAT, Benjamin Chun, See-Ming Lee