You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

I met all kinds of interesting people at the recent Disquantified conference on finding meaningful metrics in higher education including the author of today's guest post, Zachary Bleemer, a PhD candidate who did a presentation that looked underneath the promises of wage-by-major data that raised a number of concerns about how transparent the data being gathered and shared truly is. I asked if he'd be interested in doing a guest post on the topic and I'm grateful he was open to the invitation. - JW

--

Wage-by-Major Statistics: Transparency to What End?

By Zachary Bleemer

According to a 2015 report from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce (CEW), Philosophy majors earn lower median wages than Biology majors by about 10 percent, or $5,000 per year. One interpretation of this difference would suggest that an education in Biology increases a student’s labor market opportunities, enabling them to earn higher wages when they seek employment after graduation. That interpretation would suggest that if a student intending to major in Philosophy decided to switch and major in Biology instead, she could expect to increase her future earnings by around 10 percent, a meaningful difference that could be enough to convince her to switch fields.

In theory, greater transparency about past students’ outcomes should enable current students to make better decisions. This is the rationale behind net cost calculatorslike the excellent MyinTuition, which provides easy-to-use, personalized, and accurate estimates of specific applicants’ net enrollment costs.

Now the stars of political fate appear to be aligning around the creation of a nationwide public database of median postgraduate wages by university and major. Will these data be similarly useful to college students as they choose their field of study?

The conception of the database goes back at least to 2015, when CEW published a major report estimating “the economic benefit of earning an advanced degree by undergraduate major.” The report presented nationally-representative wage-by-major statistics showing that “the top-paying college majors earn $3.4 million more than the lowest-paying majors over a lifetime.” Anthony Carnevale, the director of CEW, argued in the New York Times that “there should be much more information available to students about employment and wage prospects before they choose a major so that they can make informed choices. ‘We don’t want to take away Shakespeare. We’re just talking about helping people make good decisions.’”[1]

Since then, the University of California and the University of Texas systems have built interactive websites that allow students to see average postgraduate wages by major for each of their campuses. Mark Schneider, president of the American Institutes for Research’s College Measuresresearch group—which was dedicated to producing wage-by-major reports and online tools for other public universities—joined the Trump administration as Director of the Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences. The Wall Street Journalreported last August that the administration would “require colleges to publish data on graduates’ debt and earnings by major,” and the President issued an executive order to that effect in March.[2]

But there are many reasons that postgraduate wages differ between students with different college majors, not just the “causal” interpretation in the first paragraph. Three alternative explanations—non-random selection, measurement limitations, and the challenge of extrapolation—are particularly salient.

First: selection. Students don’t randomly choose their majors, so a comparison between the wages of graduates with different majors is far from apples-to-apples. For example, consider how university policies limit access to some majors by ‘selecting’ chosen students:

- Separate applications to engineering schools, which often require higher standardized test scores or additional high school science training;

- Hard restrictions on who can declare each major: freshmen may have to earn high grades in introductory courses to major in cognitive science or economics, or sophomores might have to apply to a university’s business major on the basis of their on-campus leadership activities;

- ‘Soft’ requirements intended to push students out of certain majors: professors may try to discourage students out of engineering or mathematics majors by assigning low average grades.

These restrictions are themselves correlated with future earnings: one reason that engineering majors earn high wages is that that students able to major in engineering already had measurable aptitudes rewarded by employers. But just because those selected into a given major earn more after graduating doesn’t mean youwill, too.

Another source of selection comes from students themselves. A 2017 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economicsshowed that students have different future employment preferences—some prioritize wage growth, others flexibility, and still others job stability—and they choose both college majors (e.g. economics for high wages, humanities for flexibility) and their postgraduate employment accordingly, based on their perceptions of others’ outcomes. As a result, the kind of student who wants high wages will choose to study economics and then accept high-wage employment, though that student might have chosen to obtain high-wage (but long-hour, low-flexibility) employment even if she hadn’t studied economics. Did studying economics increase students’ wages, or did students pursuing high wages study economics?Both may be true, but the latter would bias economics’s wage-by-major estimates upward.

A 2004 study in the Journal of Econometricsfound that STEM majors from the 1980s earned about 40 percent more than workers without college degrees, but that half of the wage difference could be explained by these non-random differences in “selection”. In other words, the kind of person that majors in STEM would have earned high wages even without the degree, but correlation doesn’t imply causation: switching to major in STEM won’t necessarily lead others to those same high future earnings.

Next: measurement. Existing wage-by-major estimates are plagued by severe data limitations. Some present self-reported wages from self-selected alumni, while others are restricted to alumni who happen to still work in the state where they earned their degrees. Some only show wages for graduates within 2-4 years after they leave college, when many remain in graduate school or otherwise haven’t yet begun their careers.[3]A nationwide database using data from the IRS would overcome these limitations, but other more-fundamental data issues would remain:

- Wage-by-major statistics are estimated only for graduates, but not everyone choosing a major will graduate, and some majors may lead to lower drop-out rates than others. Excluding non-graduates will make high-drop-out majors (often professional fields) look more remunerative than they actually are.[4]

- Wage-by-major statistics only cover reported incomes, excluding the unemployed, homekeepers, the self-employed, and workers who earn unreported wages. As a result, majors that lead graduates to low-paying and off-the-books jobs (like the Arts) will be penalized relative to majors that lead graduates to relatively high unemployment (like Geology).

- Wages don’t correspond one-to-one with quality of life, especially because of cost-of-living differences in different regions. Psychology is the most-popular major in most Northeast states, while biology is most popular in the Southeast. Prices are lower in the Southeast, so biology majors are relatively better-off than their statistics suggest. To take another example, economics majors tend to live in high-cost-of-living cities, making their high wages less valuable than they would appear.[5]

These limitations may look negligible alone, but they can add up to substantial biases in estimated wage-by-major statistics.

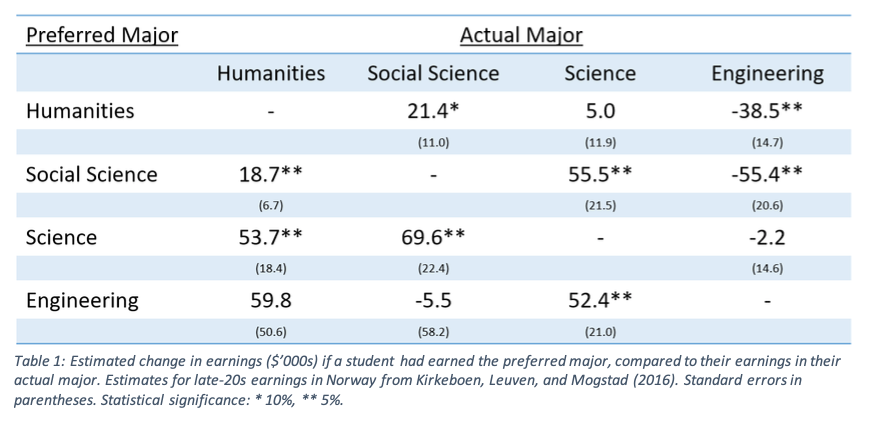

Finally: extrapolation. Even if majoring in the natural sciences causes people on average to earn higher wages, does that mean that any specific student should major in science? The most-comprehensive study on that subject was published in the Quarterly Journal of Economicsin 2016, studying university applicants in Norway, where major-specific university admissions are centrally organized. The authors matched students who had the same preferences between majors—first choice humanities, say, and second choice social sciences—and then compared the earnings (more than 10 years later) of those who were assigned their first choice to those assigned their second choice. This table shows how many more thousands of dollars per year the second-choice students (who earned their “Actual Major”) would have earnedif they’d been able to earn their “Preferred Major” instead:

Nearly all of the numbers in the first three columns are positive, implying that students would have had higher earnings if they’d been able to study in their preferred field. The authors call this students’ “comparative advantage” across fields: students who prefer the social sciences will earn more if they study the social sciences, while students who prefer the humanities will earn more after studying the humanities. That’s not true for engineering—earning an engineering degree (or other professional degrees, omitted here) increases wages no matter students’ preferences—but it’s broadly true in the liberal arts and sciences. Just because a major increases students’ future wages on average—and indeed, some majors probably do, despite wage-by-major statistics’ negligible usefulness—doesn’t mean that it would increase everyone’sfuture wages.[6]

So: how actionable are wage-by-major statistics to students trying to choose a field of study? At least as currently-conceived, there is little reason to think that choosing a “higher-wage” field will actually lead a student to higher future wages. While these statistics are supposed to be helpful for students who want to earn higher wages, instead they are an amalgamation of selection effects and measurement issues that terminally confound practical usage. Even if those issues were solved, no student is average: those with a comparative advantage in one field are often ill-served switching to another.

Unlike net cost calculators, wage-by-major statistics are not detailed, personalized, or fundamentally relevant to students making their college major choice. While they could be improved—e.g. by including non-graduates and self-employment income, adjusting for cost-of-living differences, and using statistical tools to correct for selection bias—it is hard to see how the currently-proposed database would benefit American students.

BIO

Zachary Bleemer is the director of the University of California ClioMetric History Project at UC Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education.He has published studies on affirmative action, the consequences of student debt accumulation, perceived university costs, state disinvestment in public higher education, and youth natural disaster exposure in outlets including the Journal of Public Economics and the Journal of Urban Economics. Zach also holds a research position at the UC Office of the President and is a 2019 National Academy of Education / Spencer Dissertation Fellow at UC Berkeley, where he is a PhD candidate in Economics.

[1]Here’s Times columnist Ron Lieber’s similar exhortation: “In my ideal world, every parent and potential student would be able to search program by program, school by school, to see who dropped out, who finished with how much debt, how much progress they were making on repaying the debt and how much the graduates from each program earned years later, on average. Full transparency.”

[2]Rick Seltzer has extensively covered the federal wage-by-major database for Inside Higher Ed; take a look at his May article on a closely-related newly-formed commission funded by the Gates Foundation.

[3]A landmark 2017 study by Raj Chetty and coauthors shows that postgraduate wage-percentile profiles (that is, what percent of same-age American workers you earn more money than) don’t stabilize until workers’ mid-30s; more- and less-selective universities’ graduates’ annual wages look similar through their mid-20s, but have sharply diverged (in favor of more-selective graduates) by age 32. See Figure II.

[4]For example, an in-depth 2013 study of students at Berea College published in the Review of Economic Studiesshowed that students are more likely to drop out if they enter that school intending to study professional fields like education or agriculture.

[5]Calculations from the American Community Survey.

[6]A recent working paper found similar results studying college-goers in Denmark. Scandinavian postgraduate wages are more compressed than wages in the US, suggesting that the dollar value of comparative advantage might be even larger in the States.