You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

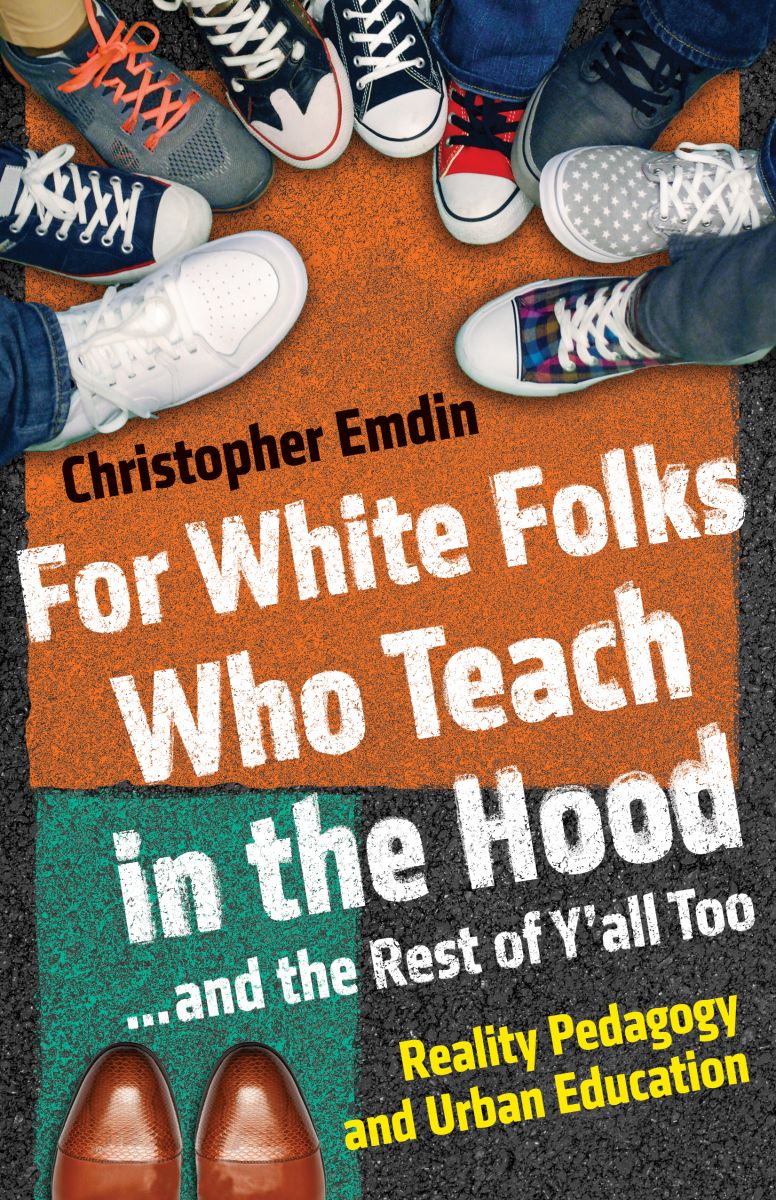

By its title, For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood…and the Rest of Y’all Too by Dr. Christopher Emdin isn’t for me.[1]

I am indeed white folks, but I do not teach in “the hood.” I also teach college, rather than in the K-12 system that Dr. Emdin is addressing with this book, and yet over and over again, I found myself underlining passages and thinking about how they might apply to my college writing classroom and my own teaching practice.

Dr. Emdin is an associate professor in the Department of Mathematics, Science, and Technology at Teachers College, Columbia University. Unlike “education tourists” who get splashy book publicity campaigns or made their fortunes in software, Emdin also has extensive experience teaching in the secondary education classroom.

It is what Emdin perceives as his failures in his first year teaching in an urban school that provides the roots for the inquiries of For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… Despite having been raised in a neighborhood like the one he was teaching in, he found himself “nervous” on his first day as he anticipated facing the students.

The categorization of which students were “teachable” or the opposite, “good,” or “bad” became “a game of sorts” for Emdin and the other teachers. He was counseled to not express too much emotion less he appear vulnerable and to “stand your ground when they test you.”

“Don’t smile until November” became the teachers’ mantra. School was a battleground between teachers and students; the teacher’s job was to civilize the savages.

Reflecting on the alienation he once felt as a student and increasingly dissatisfied with what he was experiencing in the classroom, Emdin began to remake his teaching, first by facing the fear he held for his students. “Somehow, the stories about angry and violent urban youth who did not want to be in school and did not want to learn stripped them of their humanity, erasing the reality that they were just children on their first day of school.”

The result is Dr. Emdin’s “reality pedagogy,” and it is this concept that I believe anyone who has found themselves inside a classroom should spend some time grappling with.

Even if you do not agree with it, it is impossible to dismiss.

In Emdin’s words:

“Reality pedagogy is an approach to teaching and learning that has a primary goal of meeting each student on his or her own cultural and emotional turf. It focuses on making the local experiences of the student visible and creating contexts where there is a role reversal of sorts that positions the student as the expert in his or her own teaching and learning, and the teacher is the learner.”

Emdin’s reality pedagogy resonates because over the last couple of years I have been wrestling with my relationship to my work and my students. Having lost faith in a process that places the instructor at the center of the course as a vehicle for deep, meaningful learning, I’ve been seeking out alternatives, like “writing related problems” instead of essays and the use of a grading contract.

Most of all, I’ve been much more engaged with asking my students about their experiences in the world. When they say a course or assignment is “boring,” rather than declaring, “Only boring people get bored!” I ask students about their boredom. When they don’t do the reading, rather than assuming lassitude or entitlement as I have in the past, I ask them, “Why not?”

These inquiries have taught me much about my teaching, and are quickly becoming the core of my practice. I’ve found that my students value many of the same things I do, it’s just that they situate those values differently from me. My students and I both agree that learning and curiosity are important. But they don’t experience school as a place where learning happens, or where curiosity is valued. Knowing this, I can address this need in the assignment design and class discussion.

Emdin put his reality pedagogy into practice by seeking to more deeply engage in the culture and practices of the communities he was working within.

He went to church and noticed how, from the pulpit, the preacher was able to keep audiences engaged with a combination of the emotional, the intellectual, and the personal. Rather than not smiling until November, it suddenly seemed more sensible to ask the class to share the good news, a call and response that demonstrated engagement and enthusiasm far better than upright posture or primly crossed legs. In the preacher he saw teaching as an “awareness of the delicate balance between structure and improvisation.”

In the “rap cypher,” a spontaneous freestyle group jam, Emdin saw a model for engaging with and valuing the student voice. He created student “cogens,” discussion subgroups where the teacher would solicit student expertise in how to manage the class. These students become ambassadors that help translate instructor goals into the culture of the classroom. Rather than demanding compliance, he elicits cooperation.

Each chapter of For the White Folks… is structured around these practical approaches to the classroom, but for me, it is the philosophy they collectively articulate that is most important, and I believe worthy of emulation. Emdin argues that if we are to educate, we must treat students as the complex and contradictory individuals we know them to be.

Our goal as educators cannot be to subjugate students to abstract ideals – ideals that often take on systematically racist forms when applied to black and brown urban students – but to work inside the communities, drawing on their strengths and using those strengths to foster learning.

Even as reading the book made me realize how the vast majority of the money going into so-called education reform (“no excuses” charters, standardization, Teach for America) is heading the opposite direction of Dr. Emdin’s humane, and more importantly, effective practices, it filled me with great hope and excitement to keep engaging with the community in which I teach.

There is another way of dong things.

Later this week I’ll be publishing a Q&A with Christopher Emdin that will hopefully provide even more fodder for discussion.

[1] I've read lots of great books on teaching, but the last one to have a similar impact was Ken Bain’s What the Best College Teachers Do.