You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Courtesy of Drew McKevitt/Louisiana Tech University

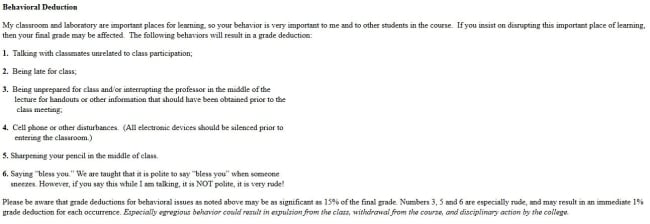

Drew McKevitt has taught more than 20 sections of Intro to World History during his seven years as a professor at Louisiana Tech University -- each with as many as 180 students. This fall, he wants to shake up the format and start engaging his students with a flipped model -- instruction at home, active learning in the classroom.

Flipped classrooms aren’t new, and among higher education professionals they’ve become increasingly popular and well-known as the body of research about their value grows. But McKevitt thought students expecting a traditional lecture might balk at his new approach, so he created a syllabus document that anticipates such concerns.

“This is my first time experimenting with a syllabus that's anything but the typical thing that looks like a legal contract, so it's most definitely still a work in progress,” McKevitt said.

When he tweeted an image of the syllabus last week, he got helpful feedback that will inform his thinking about the course going forward. One message he heard loud and clear: remove the phrase “flipped learning.”

“I’d personally beware of using educational terminology,” said Robert Talbert, a professor of mathematics at Grand Valley State University who published a book last year about flipped classrooms. “Especially if it’s explicitly or implicitly saying it’s brand-new or different or experimental, students will immediately get the sense that this is a risk, this is not tried and true, ‘we’re uncertain we’re going to get what we’re paying for.’”

Talbert believes a growing number of students will have been exposed to flipped classroom experiences in their K-12 classrooms. They might not necessarily know that what they experienced was flipped, however, and if they do, they could bring preconceived expectations of the flipped format with them to higher ed.

More from “Inside Digital Learning”

Experts weigh in on the merits and limitations of flipped classrooms.

A new for-profit initiative wants to create global standards for flipped classrooms.

A music course in Maryland aims for a "double flipped" model.

On the other hand, students who haven’t heard about flipped classrooms might perceive them as a risky experiment in which they prefer not to take part.

“I had a parent once call my university to complain that I was experimenting upon her students without [institutional review board] approval,” Talbert said. “Students don’t need to know that stuff; they need to know what they’re going to be doing, their benefits.”

José Antonio Bowen, president of Goucher College and a proponent of active classroom learning, also thinks students will glaze over “the jargon of the month.” But he believes McKevitt’s goals for transparency are apt.

“Students want to learn, so if you are using evidence-based teaching and you tell them that you know or research shows that students learn more when we design classes this way, then that is motivating,” Bowen said.

Though McKevitt agrees that he has a tendency to “overexplain,” he thinks his style might be useful at his institution, which primarily serves students from Louisiana high schools who tend to come to Louisiana Tech with “no real college literacy” or expectations for the additional layers of academic rigor that postsecondary instructors bring to the table.

“Lots of our students show up in my class on the first day expecting an intro-level class in a large lecture hall to be just like all the other intro-level classes in live lecture halls. They enter passive absorption mode and then they expect me to tap-dance for two hours,” McKevitt said. Some even express in student evaluations that they prefer to let the instructor take the lead.

“I want to make clear in this document what they’re going to see even before they step into the classroom,” McKevitt said.

Yakut Gazi, associate dean of learning systems and professional education at Georgia Institute of Technology, has another reason for wanting to avoid explaining flipped classrooms to students -- she doesn’t like the term even among professionals, and prefers “inverted learning.” She also thinks “flipped learning” isn’t easily boiled down to a single definition, given that it can be done simply by assigning readings out of class or by applying technology tools.

McKevitt hopes his flipped-classroom experiment will be successful. If not, he can seek guidance from Dirk Moses, professor of modern history at the University of Sydney, in Australia. Moses documented his experience flipping a history class, but he’s reverted to a more traditional format after students in his first-year course said they didn’t find small-group work fulfilling.

“Flipped classrooms work better with a) smaller groups and b) more advanced students who are better able to assume the responsibility for self-learning,” Moses said.

McKevitt will test this theory next semester. Intro to World History has the largest sections of any course at the institution, and it serves as many students' only exposure to the humanities as they make their way toward a technical degree.

"Everything’s new to them," McKevitt said. Also in the class, though, are a handful of senior engineering majors who expect him to "dump everything" they need to know into their heads so they can pass the exam and forget about the class once it's over.

"There’s a wide range of experience that comes into a class like this," McKevitt said. "I want to be sensitive to that."