You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Business schools dominate online executive education, for good reason. But leaders at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles believe they’ve identified a gap in the market: teaching basic legal skills to business professionals.

The law school, part of private nonprofit Loyola Marymount University, is today launching an executive education program called LLX.

Michael Waterstone, Fritz B. Burns Dean of Loyola Law, said the motivation behind the program is to open up legal education to a “wider range of executives and professionals.”

Law schools have been slow to embrace online education due to a combination of tradition, accreditation limits and state regulation. But after years of falling enrollments and some institutions even closing their doors, leaders like Waterstone are looking to innovate.

While LLX’s mission is ostensibly to make legal knowledge accessible to people without law degrees, the law school still wants to make money. Admissions will be selective, and the six-week courses will cost around $1,000. In addition to online courses, LLX will also provide on-campus courses and is open to teaching bespoke curricula on-site at company locations.

“What we’re looking to do is deliver our core product to a different universe of people that could use it and have the ability to pay for it,” said Waterstone.

The development of LLX occurred at “light speed” on a six-figure budget, said Waterstone. Discussions about the program began a little over a year ago. Such fast-moving projects are rare in academe, but Waterstone approached the project with a “start-up mentality,” he said.

Central to the project’s success was finding the right person to lead it, said Waterstone. “We needed someone who understood what the start-up world looks like, but who also understood the law side. We wanted someone who could work lean and take some risks -- who could move fast and break things.”

That person was Hamilton Chan. Now director of executive education at Loyola Law School, Chan’s résumé is impressive. A Harvard Law School graduate who worked at a top law firm, Chan has also worked as an investment banker, a movie studio executive and an entrepreneur. He can code, too.

Chan said an important first step in the project was building support among the law school's many constituents. “People have notions of what the Loyola brand should be -- there were concerns about diluting that,” he said. Convincing the faculty, alumni, Board of Directors, parents and everyone else in the Loyola ecosystem that this is a good idea “took a lot of groundwork in the first few months.”

With a team of five engineers, Chan built an online platform in six months. He had a lot of freedom to pursue his vision for LLX, he said. There was an understanding among senior administrators that he needed space to innovate, “or it wouldn’t work,” he said. He didn’t consider bringing in another company to build the platform. “You wouldn’t expect a start-up to outsource the development of a platform -- it would be foolish,” he said.

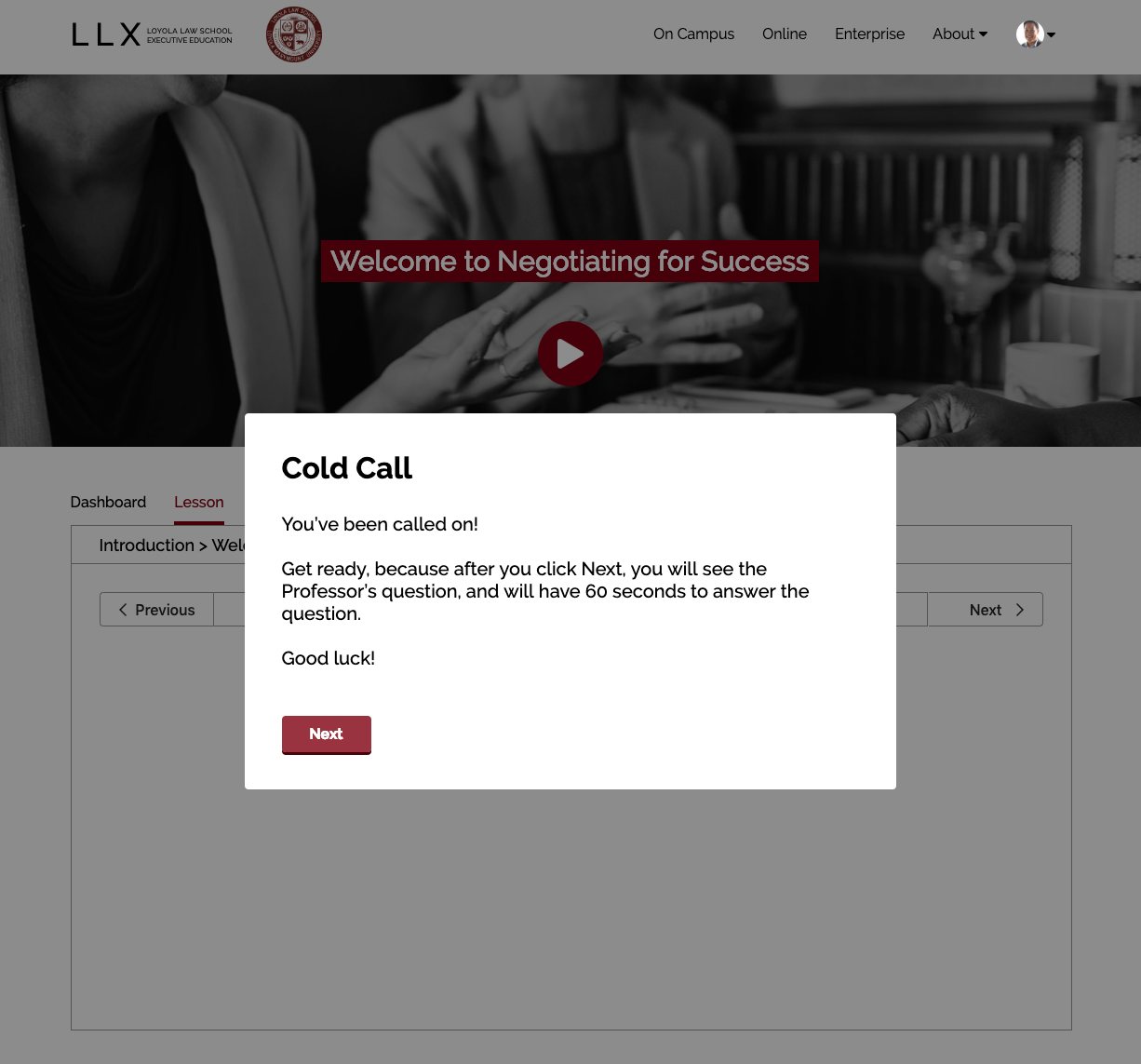

The online platform was designed to offer students an interactive learning experience, said Chan. In addition to watching preproduced instruction videos, students will work through “choose your own adventure”-style exercises in addition to polls, quizzes and fill-in-the blank questions. LLX will also employ “cold calls” to ask students questions under time pressure -- a popular technique at business schools.

The courses offered by LLX will be non-credit-bearing certificates, said Chan. The first course to launch will be called Negotiating for Success and will be taught by Chan himself. The second course will be Intro to Contracts, slated to open for enrollment this summer. Subsequent courses will include titles such as: What to Expect When You’re Expecting a Lawsuit, How to Actually Practice Corporate Law, Protecting Your Intellectual Property and Marijuana Law.

Craig M. Boise, dean and professor at the College of Law at Syracuse University, said many law schools have been thinking in recent years about “how they can take their core product -- understanding the law” to a wider market.

Several schools have established law degree programs that are online hybrids, said Boise. But few have explored outside the realm of continuing legal education. “There is a market out there for providing legal education to people who don’t want to practice,” said Boise. “I applaud Loyola for thinking outside the box.”

Loyola is a well-known law school, particularly in Los Angeles. But whether its online certificates will have national appeal remains to be seen. “Very few schools, with the possible exceptions of Harvard and Yale, have brands that are going to carry a lot of weight,” said Boise. This is not a criticism of Loyola, he said. Syracuse has in the past decided against offering online certificates for this reason. “Certificates have got to have some currency,” he said.

Jack Graves, professor of law and director of digital legal education at the Touro Law Center, said it is “not at all surprising” that schools like Loyola are starting to move in to the executive education space. “I think it’s the next logical step,” he said. Graves said many areas of law -- contracts, negotiations and compliance -- “are valuable directly to businesses.”

Offering legal education to business professionals raises some “complex issues,” said Graves. By educating business professionals in the law, there’s a possibility law schools may be taking away future clients from their students. On the flip side, “an educated client knows when she needs a lawyer,” said Graves, and may be easier to work with.

Waterstone, dean at Loyola, said he has thought about this issue. “We want to be very clear that we’re not going to make people mini-lawyers. We want them to be more sophisticated users of legal services.”

Trace Urdan, managing director at Tyton Partners, a education investment banking and consulting firm, said the idea of a law school taking its brand and going after nondegree offerings is potentially “ingenious.” But Urdan said he had several questions about LLX’s strategy. “Continuing legal education is an established market with established revenue streams,” he said. What LLX is doing is “a much more risky, entrepreneurial undertaking -- they’re trying to create a market that doesn’t really exist.”

Executive education is already flooded with business schools teaching students negotiating skills, but Urdan could see a subset of professionals “who might think a law school can teach me something about negotiations that a business school can’t.”

Urdan predicts many law schools, particularly those looking to diversify their revenue streams, will be watching LLX. “If it’s even remotely successful, I think others will follow,” he said.

Urdan predicts there may also be an opportunity for online program management companies to help launch and run online programs for the law schools. “Trying to construct everything internally takes a lot of political capital to get done,” he said.

“I think a lot of OPMs will be looking hard at this space.”