You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

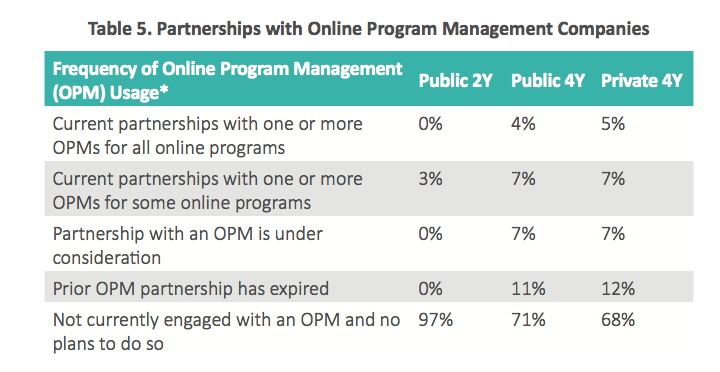

Below is a revealing table on the Online Program Management (OPM) industry in the recently released Quality Matters-Eduventures report called The Changing Landscape of Online Education (CHLOE).

For those of you who don’t know much about the $1.1 billion OPM market, I highly recommend reading this 2015 Inside Higher Ed article, A Market Enabled: Where is the Billion-Dollar Online Program Management Industry Headed? I also recommend Phil Hill’s 2016 piece Online Program Management: A View of the Market Landscape. And for a more critical view of the OPM market, check out the 2016 Atlantic article How Companies Profit Off Education at Nonprofit Schools.

The basics of the OPM business model involves a company/institution partnership to develop, market, launch, run and support an online (or low-residency) degree program. Traditionally, the OPM partner provides startup capital and absorbs much of the financial risk, while offering services (that can sometimes be unbundled) around marketing/recruitment, course design, technology and student support.

In exchange for investing the money and other resources to launch and run the online program, the OPM provider takes a proportion of the revenue (between 50 and 70 percent -- sometimes more or less) in a long-term contract agreement (7 to 10 years) that allows the OPM provider to realize a return on its investment.

Table 5 above should make anyone who works for an OPM provider sit up and take notice.

The percentages that I’d most be concerned about if I worked for an OPM company are those in the bottom row. About 7-in-10 chief learning officers at public and private four-year institutions who responded said they are "not currently engaged with an OPM and [have] no plans to do so." [Emphasis mine].

It is difficult to tell what “no plans to do so” means. The worse scenario is that chief online learning officers are not spending the time and effort to learn about and understand the OPM market. An almost equally bad scenario is that there is little understanding of the options and opportunities that an OPM partnership may provide across institutional leadership and various campus stakeholders.

My strong belief is that the OPM option should be understood, explored and discussed on every campus. This does not mean that a partnership and a revenue share model are right for every school and every program. Rather, the partnership route should be considered and understood as a possible option.

In reading the CHLOE report, one of the strong takeaways is that online and low-residency programs are an economically sustainable option. The report notes that “The majority of our study’s sample view online programs as revenue generators rather than drains on resources.”

As I’ve previously noted, it is a myth that online programs need to enroll large numbers of students to be economically sustainable. In fact, relatively small programs -- ones built around institutional strengths -- can be both economically viable and align with other strategic goals of differentiation and quality improvement.

The main reason that schools don’t build smaller programs around their strengths is the direct and opportunity costs involved in doing so. Money is tight everywhere, and if you focus people and time and resources on a small online program than other institutional (or school/department) initiatives will have to be put on hold.

It is for these reasons that looking at OPM partnerships for small online programs might make sense.

Of course, every OPM provider would rather partner with a school that wants to scale its programs. These same OPM providers, however, should come to an understanding that partnering on small programs might be the most viable strategy for growing and sustaining their businesses. A small program can build knowledge, trust and relationships at a school. It also can be financially viable to all parties, while laying the groundwork for larger online programs should those opportunities emerge.

On the institution side, work with an OPM partner may enable a small program (one built around institutional strengths) to actually launch. The only thing worse than sharing revenues is having no revenues at all. The OPM option should be on the table for discussion.

That is why you and I should worry about the CHLOE results -- 7-in-10 "not currently engaged with an OPM and [have] no plans to do so" -- and take these data as a call to action.

The More Options the Better

Everyone in the online learning ecosystem -- those of us who work on online learning within higher ed and those who work for the OPM providers -- should be working to get the partnership option on the table. More information and options are never a bad thing.

Building an appetite to investigate the OPM option within higher ed -- and particularly around smaller schools and potential online programs -- will be a challenge. The OPM market is a crowded and confusing space. At my count, there are at least 13 OPM providers -- maybe more.

Those of us who work in higher ed on online learning don’t really understand how all of the players in the OPM space differentiate themselves from one another. And we assume (my guess incorrectly) that a potential small online program on our campus would not be of interest to a potential OPM partner.

How can we expand the idea of the OPM model to small online programs? What would be necessary to change the results in future CHLOE surveys so that more chief online learning officers are committed to learning about the OPM option?