You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The online program management space is booming.

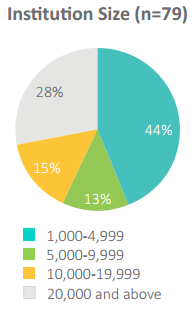

Eduventures, a Boston-based higher education research firm, estimates the market is worth $1.1 billion. The firm this spring surveyed academic leaders at more than 175 colleges and universities to form a picture of the companies known as online program management (OPM) providers, or enablers. These companies help institutions bring their programs online, taking a share of tuition revenue in return.

What Eduventures got in response to the survey was a snapshot of the educational technology market. Survey respondents named 36 different start-ups and established companies, among them companies that operate solely in the space, such as 2U, but also Cengage Learning, known primarily as a publisher, and Jenzabar, an administrative software provider.

Max Woolf, the senior analyst who wrote the report, said recent entrants into the market have fueled competition but also pushed companies to differentiate themselves.

“It’s a very fragmented market, but there’s a lot more competition than there was, say, five years ago,” Woolf said. “It’s raised the game across the board.”

Everyone wants a piece of the market, but where the market is headed is anyone’s guess. Some analysts see acquisitions and consolidations in the future; some see more upstarts and experimentation. Among the companies themselves, some anticipate expanding into international markets and alternative credentials, while others maintain they will continue to target one particular sector of higher education. Others yet argue that the market is ready for a reboot, and that companies should focus on becoming experts at offering specific services.

What they all agree on, however, is growth.

The Eduventures survey found a 50-50 split between those colleges that are current or prospective customers of OPM providers, and those that aren’t currently interested or don’t know. Woolf said he viewed those numbers from a “glass half-full” perspective.

“There are plenty of institutions where it’s just not the right cultural fit, and it’s more an acknowledgment that the fit isn’t right for an OPM than it is a downside to the market,” Woolf said. “There is a huge, huge opportunity and upside in the majority of the market that doesn’t work with OPMs today.”

Enabling International, Adult Students

Working adults in the U.S., and college programs that target those students, are expected to account for much of that growth.

“Where the real population lies is at the bachelor level,” said Chris Montagnino, vice president of extended education at Excelsior College and CEO of Educators Serving Educators, which is a rare nonprofit entity among the OPM providers. “Most institutions have yet to warm up and serve nontraditional students who have less than 60 credit hours. That’s the key.”

Ignoring the needs of adult students “is to ignore 71 percent of the addressable market,” Academic Partnerships CEO Randy Best said, referring to the students not between the ages of 18 and 22. “Schools are in a position to need enrollment, need to grow their revenue, so it must come from expanding their service area.”

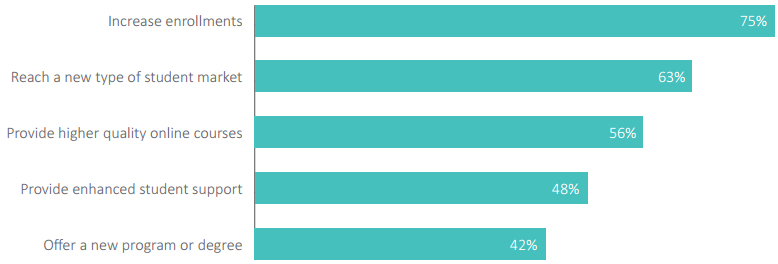

Best’s comments echoed Eduventures’ findings about why colleges choose to partner with OPM providers in the first place -- a decision that in some cases costs institutions about half of the tuition revenue generated by the online programs. In the survey, three-quarters of respondents said their main priority was to increase enrollments. Reaching new student markets placed second, at 63 percent.

Academic Partnerships, which mainly works with public institutions, is one of a handful of OPM providers that see an opportunity for growth internationally. The company last year launched a new initiative, Specializations, for institutions in English-speaking countries to extend their reach to countries such as China, India and Mexico.

Best described the international market as the “greatest opportunity” for colleges -- aided by their brands and a lack of access to higher education in emerging economies -- to expand their online enrollment. “Over the next five years, U.S. schools will see a significant portion of their student body becoming international students, and those students will be primarily online,” he said. “We’ll be exporting our education versus importing the student.”

Academic Partnerships is not alone in pursuing the international market. Steve Fireng, CEO of Keypath Education (which recently changed its name from PlattForm, and expanded its focus beyond marketing for students), said the company is looking to expand abroad. The company last week announced a major expansion in the United Kingdom and has its sights set on Australia, where it sees “little competition.”

Best said the market has recently experienced a “little lull” in the number of institutions partnering with OPM providers, but added that he expects a “substantial increase” early next year, based on conversations with college leaders. The growth is likely to be fueled by colleges with existing partnerships adding new online degrees, he said.

The opportunity to expand in the U.S. is why 2U won’t depart from its business model, co-founder and CEO Chip Paucek said. The company, which went public last year and has been valued as high as $1.5 billion, has added several prestigious institutions to its list of partners since launching in 2008, including Georgetown and Yale Universities.

“One of the reasons people expand out of their core market is to see growth, and we are seeing plenty of growth in our core market,” Paucek said. “We’ve had quite a few opportunities to go outside higher ed or into education like K-12 or corporate training. We’ve chosen in every case to say no. You will not see us expanding outside our core business any time soon.”

A Consolidated or Crammed Market?

The OPM market has already experienced consolidation. In October 2012, John Wiley & Sons bought Deltak. Two weeks later, Pearson bought EmbanetCompass (itself a product of a merger), adding to its 2007 acquisition of eCollege.

The following years have been marked by several new companies entering the market, but there are now scattered signs that the number of providers could contract. Earlier this year, the Learning House bought Acatar, a Carnegie Mellon University spin-off. Best also said “several” companies have approached Academic Partnerships about joining forces. The company has decided against the acquisition each time, he said.

Those examples may not signal the beginning of a new shopping spree in the market, however.

Montagnino said she believes more companies will enter the market for the time being, since no single company has discovered the “secret sauce” to becoming the market leader. And as the number of companies increases, some may experiment with different forms of credentials and fee structures to find a niche in the market, she said.

“The OPM market won’t simply be online programs,” Montagnino said. “As the market continues to emerge, you’ll see it’s competency-based, hybrid, maybe even stackable credentials.”

Some of those companies are likely to fail, Paucek said. “There’s no question there will be consolidation,” he said. “That’s normal.”

With venture capital and private equity firms continuing to invest in ed-tech companies, some of those funds will find their way to OPM providers. HotChalk, for example, is reportedly talking to investors about raising at least $75 million, according to Reuters.

The financial barriers to entry may prevent even more companies from joining the OPM market, Best said. He estimated it costs $3-4 million to bring a university online, saying it takes years before companies see any return on that investment.

“There is a break point where you can grow and pay for your growth primarily out of programs that have been online for some period of time, but it’s a slow, slow, slow start,” Best said.

Even if a start-up can afford the initial investment, some colleges may feel safer working with an established company, said Don Kilburn, president of Pearson North America.

"People are looking for someone to trust," Kilburn said.

Comprehensive, Unbundled or Both?

The high initial outlays seen in the OPM market may be most of an issue for nonprofit companies. Excelsior launched Educators Serving Educators (ESE) in 2010 to serve as the college’s OPM division, but the business quickly “flatlined” because the traditional model of covering start-up costs and recouping them through tuition revenue sharing didn’t align with the college’s “risk intolerance,” a spokesperson said.

Montagnino joined the college about 20 months ago, and ESE has since shifted to become something of an intermediary between colleges and OPM providers. The company offers services such as consulting, development and marketing to colleges, and helps OPM providers with accreditation and state authorization, among other tasks.

ESE’s reinvention stemmed from a belief that “no one has necessarily figured out the perfect solution” to online program management, Montagnino said. She said some colleges need the full “meal” -- a partner that can handle every service associated with offering online programs, from instructional design to marketing, in which case ESE will refer them to an OPM provider (and earn a referral fee). Others may only need to “build a kitchen and train chefs” -- in other words, learn how to offer those services themselves, she said.

The revenue-sharing model used by many OPM providers has been particularly popular among the smaller and largest institutions, according to Eduventures.

“The middle ones think they can do it themselves,” Woolf, the Eduventures analyst, said. “They’re reticent to give away revenue to somebody else to do it.”

Some companies therefore see an opportunity to unbundle the services offered by a comprehensive OPM provider, perhaps specializing in just retention or marketing.

Ranku, a Seattle-based start-up, has long been a critic of the revenue-sharing agreements colleges make with OPM providers. The company helps colleges generate applicants by redesigning admissions portals and tracking web traffic data.

Kim Taylor, CEO and co-founder of Ranku, said she believes unbundling will become a more popular strategy as colleges learn which part of the online program management process they need help with.

“That might be retention,” Taylor said. “It might just be recruitment. … They’re going to home in on that problem, and there’s going to be someone like us that’s 10 times better at recruitment than someone who does everything.”

Unbundling could lead to a single college working with multiple OPM providers to take their programs online -- a concept that may not appeal to the comprehensive providers that have invested millions to bring the programs online.

“I don’t think it’s wise for institutions to work with multiple providers,” Best said. “They’re kind of working against one another.”

There are certain services some comprehensive providers say they will never offer, however.

“We are definitely of the opinion that online enablers should know their place,” Paucek said. “What I mean by that is we are not a university. … The key competencies that you would anticipate a university to do, they do -- everything from curriculum control to admissions decisions to instruction. 2U will never hire faculty. I would rather not see people in the OPM space do that.”

Doug Lederman contributed to this report.