You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

George Cohen is the idol of many university professors these days.

The law professor, only several weeks into his term as chair of the Faculty Senate at the University of Virginia, became the central figure in the faculty’s ultimately successful efforts to get the university’s governing board to reverse its June effort to force the resignation of President Teresa Sullivan – an event that captured national attention for more than two weeks.

Many consider the Virginia faculty’s sustained protests, calls for board members’ resignations, support for Sullivan, and organized efforts during the two weeks between Sullivan’s resignation and her reinstatement crucial to the board’s vote to reinstate her.

But what happened at the University of Virginia was not an isolated incident. Leadership controversies abound these days, and in the past year, faculty members at multiple universities have pushed back against efforts to remove presidents -- sometimes successfully, sometimes not. They’ve also pushed for boards to get rid of unpopular presidents, also with varying degrees of success.

The complicated picture that emerges from these conflicts raises questions about how much authority faculty members – particularly at large public research universities, which seem to be ground zero for such disputes – have in debates about the future of their institutions. At a time when there is increasing pressure for universities to change quickly and dramatically, and institutions are vesting more authority in presidents and boards, these debates show that faculty members, when organized, can still exert significant pressure on boards.

"It’s scary to see that something like [what happened at U.Va.] could happen," said Martha Hilley, a music professor and incoming chair of the Faculty Council at the University of Texas at Austin, one of the few campuses that in the past few years have successfully rebuffed efforts by its governing board to alter its leadership. “If you’re in higher education, you’re thinking 'O.K. If it could happened there, it could happen at UT-Austin. It could happen anywhere.' "

Organized Resistance

Next to the University of Virginia, the UT-Austin situation in May might be the best example of faculty members rallying behind an endangered president. While much of what happened at Virginia was conducted in the open, the Texas board’s actions were never made public, so exactly what happened is still unclear.

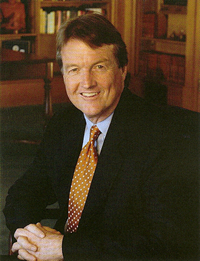

In May, Texas Monthly reported that the University of Texas system’s board was considering ousting the Austin campus’s president, William C. Powers, because Powers publicly criticized the board’s decision not to raise tuition at his campus, even though the increase he proposed was broadly supported on campus and fell within guidelines set by the board. After that report, the university community, particularly the faculty, rallied behind Powers. The university’s Faculty Council passed a vote of confidence in the president, their second in two years. No official board vote was taken on Powers.

In May, Texas Monthly reported that the University of Texas system’s board was considering ousting the Austin campus’s president, William C. Powers, because Powers publicly criticized the board’s decision not to raise tuition at his campus, even though the increase he proposed was broadly supported on campus and fell within guidelines set by the board. After that report, the university community, particularly the faculty, rallied behind Powers. The university’s Faculty Council passed a vote of confidence in the president, their second in two years. No official board vote was taken on Powers.

Alan Friedman, an English professor who was the chair of the Faculty Council during the incident, said faculty members really did believe Powers’s job was on the line and that their efforts contributed to the board backing off the subject. He said that if the board ever did get rid of Powers, which still seems like a possibility to him, they would have a Virginia-like protest on their hands.

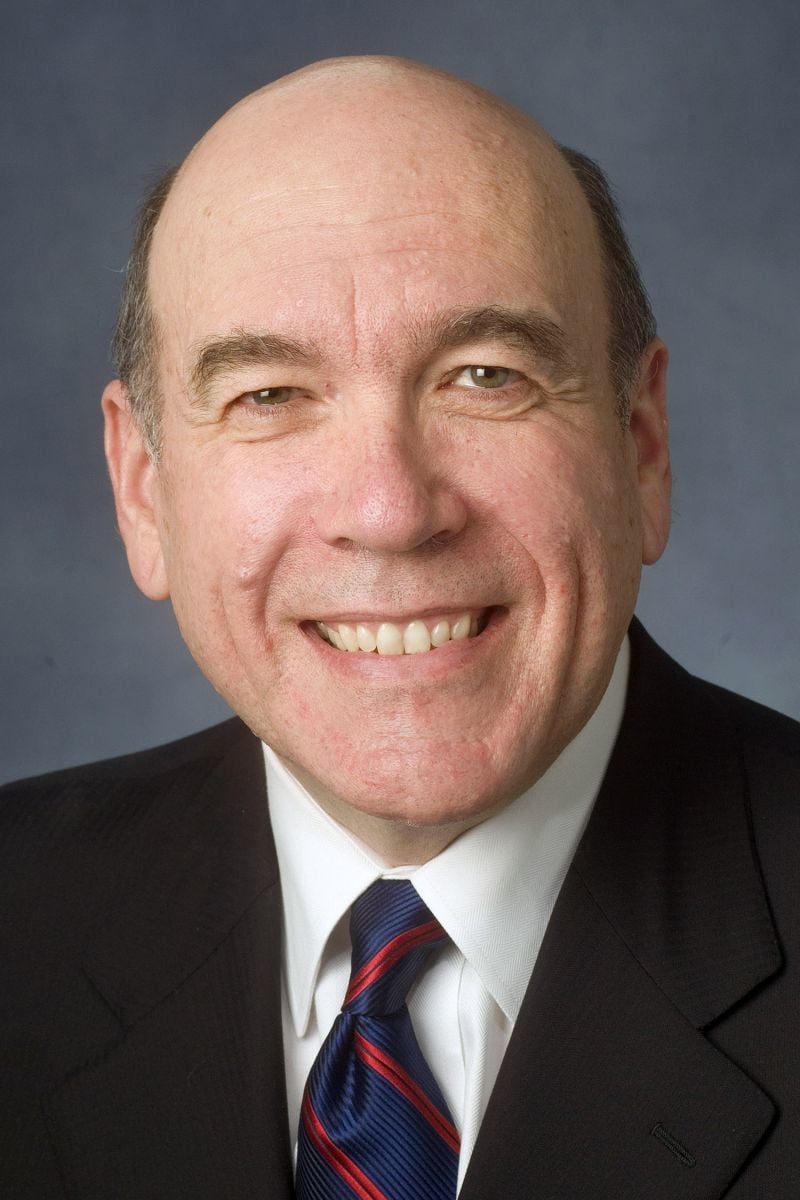

A case in Illinois represents the flip side of the debate. In February, a group of 130 distinguished faculty members, increasingly frustrated with Michael Hogan, president of the University of Illinois System, called for Hogan’s resignation in a letter to the system’s Board of Trustees. During Hogan’s 20 months in office, he repeatedly clashed with faculty members over what they saw as efforts to centralize the system and micromanage activities on the system’s three campuses.

A case in Illinois represents the flip side of the debate. In February, a group of 130 distinguished faculty members, increasingly frustrated with Michael Hogan, president of the University of Illinois System, called for Hogan’s resignation in a letter to the system’s Board of Trustees. During Hogan’s 20 months in office, he repeatedly clashed with faculty members over what they saw as efforts to centralize the system and micromanage activities on the system’s three campuses.

Despite the board’s initial expression of support for Hogan and statements by Hogan saying he was interested in repairing his relationship with faculty members, the group continued to call for his resignation. Just two weeks after the board’s expression of support, Hogan stepped down. While neither Hogan nor the board cited the faculty’s pressure as a reason for his resignation, the quick about-face led many to believe the faculty’s sustained pressure played a big role.

Why, in these instances, were faculty members able to effect significant change on their campuses? Faculty members from these and other institutions said it was a spirit of cohesion and shared purpose among faculty members, rather than any kind of formal structure or organization, that allowed them to be successful and mobilize quickly when they felt their authority on campus was threatened.

Martin Snyder, senior associate general secretary of the American Association of University Professors, said the common link between Texas, Illinois, and Virginia was that the faculty at each institution was highly unified from the start, or became highly unified shortly after news broke. “If there is a real sense of community and shared purpose among faculty members, that makes the difference,” he said.

Faculty leaders also pointed out two common features of the Virginia and Texas controversies: faculty at both institutions generally supported the president, and were unhappy about being left out of the decision-making process. “If the process is right, you’ve got a chance with the product,” Friedman said. “You have to fight for the process all the time.”

Falling Short

Despite apparent similarities in the institutions and outrage about being left out of the process, the University of Oregon faculty was not able to hold on to a president it supported when that president’s job was on the line.

In November, the Oregon State Board of Higher Education, the governing board for the Oregon University System and its seven universities, voted not to renew the contract of Richard Lariviere, president of the University of Oregon, citing his perceived failure to work with system leaders – a charge growing out of Lariviere’s efforts to gain more autonomy for the university.

In November, the Oregon State Board of Higher Education, the governing board for the Oregon University System and its seven universities, voted not to renew the contract of Richard Lariviere, president of the University of Oregon, citing his perceived failure to work with system leaders – a charge growing out of Lariviere’s efforts to gain more autonomy for the university.

Upon learning that the president’s contract would likely not be renewed, faculty members, deans, and powerful alumni launched a campaign to keep Lariviere. They were unsuccessful.

Robert Kyr, chairman of the University of Oregon’s University Senate, said differences between the governance structures of Virginia and Oregon are partly responsible for the faculty's falling short. While both the universities are state institutions, Oregon is part of a system with a statewide board and a system chancellor responsible for decisions about the president’s employment. Virginia’s board is solely focused on the interests of the one institution.

“[The Oregon state board] can say, ‘For the good of the system, the matter is closed,’ “ Kyr said. “But it can’t say ‘We did this for the good of the university' without extensive prior consultation with the faculty, which was missing with the firing of President Lariviere.” Unlike Virginia, where faculty members could argue that the board’s decision was in fact bad for the campus, which they arguably understood well, Oregon faculty members were not given enough essential information to discuss statewide priorities, Kyr said. In fact, one of the criticisms of some state officials was that Lariviere was so focused on his campus -- to the delight of professors there -- that he didn't understand the larger state context.

But the faculty's success at the University of Texas, which also has a systemwide board and no campus governing board, shows that the Oregon faculty's failure cannot entirely be attributed to that.

Others say that Lariviere might not have had the same kind of support among faculty members that Powers and Sullivan enjoyed. Friedman, who worked with Lariviere when the latter was dean of the College of Liberal Arts at UT-Austin, said Lariviere had a tendency to alienate faculty members. During his tenure at Oregon, Lariviere angered faculty members by failing to get athletics spending under control.

Others chalk up the Oregon faculty’s failure to the fact that the faculty simply wasn’t as organized and cohesive as at the other universities. Unlike Virginia and Texas, the Oregon faculty doesn’t have a single unified body to represents its interests. The University Senate includes students and university staff, not just faculty, and thus represents a broader range of interests. The Oregon vote also took place around Thanksgiving, when many faculty members weren’t paying close attention to university news.

Kyr said that the leadership debate, and the ensuing search for a new university president, was an opportunity for the chancellor, the state board, and the faculty to discuss the proper role of faculty in governance. He said that the Presidential Search Committee included diverse faculty voices, and that the selection of University of California at Irvine provost Michael R. Gottfredson as the new president reflects an emphasis on shared governance. “I’m confident that if new problems arise, we now have the means for achieving better communication through consultation and through new forms of collaboration between the university, the Chancellor, and the state system,” Kyr said.

Many say the Oregon faculty’s failure in the leadership debate helps explain why the faculty, in January, began the process to create a faculty union, a relatively rare occurrence at major research universities in recent decade. The faculty approved the union in March. “At Oregon, I don’t think there was a sufficiently organized, unified voice of the faculty, which is one years the University of Oregon faculty are now being unionized,” Snyder said.

At the same time, having a union doesn’t necessarily guarantee that the faculty’s voice will be heard.

One of the most prominent failures of faculty members to exert their will on boards over a president’s fate is taking place at Kean University, a public master’s college in New Jersey, where faculty are unionized. Since Dawood Farahi became the university’s president in 2003, the faculty has repeatedly clashed with the president over reforms. Late last year, faculty members brought a collection of Farahi’s résumés, including his application for the presidency, to the board, claiming that they were filled with errors and misleading information. Despite an independent investigation finding that the résumés contained inaccurate information, the board voted to keep Farahi as president.

One of the most prominent failures of faculty members to exert their will on boards over a president’s fate is taking place at Kean University, a public master’s college in New Jersey, where faculty are unionized. Since Dawood Farahi became the university’s president in 2003, the faculty has repeatedly clashed with the president over reforms. Late last year, faculty members brought a collection of Farahi’s résumés, including his application for the presidency, to the board, claiming that they were filled with errors and misleading information. Despite an independent investigation finding that the résumés contained inaccurate information, the board voted to keep Farahi as president.

Since then, the NCAA found that the university did not exercise proper control over the athletic department and put all the university’s athletic teams on a four-year probation. The Middle States Commission on Higher Education, which accredits the university, recently put it on probation for not meeting several of the accreditor’s standards. Even though the faculty members are unionized – which one might infer gives them extra leverage in debates about the university’s governance – they have had little success in getting the board to remove Farahi.

Kean is not the state's flagship, nor is it a research university. But faculty members at Rutgers University, which fills that niche in New Jersey, are also unionized and for years have failed to stop administrators from spending so much money on sports, a longstanding battle.

Too Much Power?

Despite a refrain that faculty members are losing their influence at colleges and universities, the handful of cases show that, in certain instances, such as at major research universities where faculty members drive a lot of the reputation and can bring in significant amounts of revenue through grants and fund-raising, they can still exert influence if they are well-organized.

“Get yourself organized,” Snyder said. “It can be a really strong faculty senate or just strong policies or procedures. It doesn’t matter what the vehicle for collectivity is, the community has to stick together.” Faculty members at Virginia and Texas are not unionized, and are prohibited by law from being unionized. Nor does either faculty have a reputation for activism. At both institutions, however, there is a long tradition of faculty receiving respect from administrators, who have valued their input on both academic and nonacademic matters.

But the display of faculty power at Texas, Virginia, and Illinois also raises questions. As the Virginia case shows, a board can change its mind relatively quickly, putting the president in a vulnerable place. In such instances, it behooves a president to have built up strong support among the faculty.

But if a president is expending his or her energies to appeal to the faculty rather than the board, that could raise questions about who exactly is running the institution, particularly at a public university. If the faculty loses confidence in the president – as was the case in Illinois – then the president’s tenure could likely end soon after, even if he seemingly has the confidence of the board. What’s known about the Texas situation also seems to indicate that the reverse is true. A board unwilling to face faculty and community criticism might keep a president in who it lacks confidence.

Kyr doesn’t view this as too much of a problem. “A president must have the confidence -- the absolute confidence -- of the faculty in order to be a truly effective president,” he said. “So the faculty needs to be committed to sustaining an honest and constructive relationship with the president that is based on meaningful consultation and collaboration."

Friedman said maintaining the support of faculty does not require the president to cater to faculty wishes. He said he and other faculty members have disagreed with Powers on numerous policy issues but still respect him as a leader, which is why he went to bat for him when Powers’s job was on the line. “The administration has always listened and taken into account the faculty position,” he said.