You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Poynter

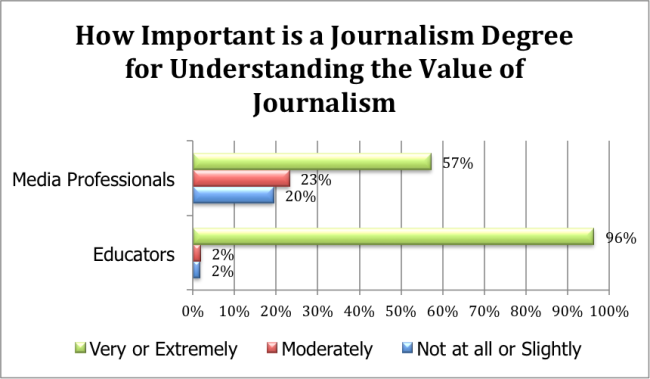

Journalism instructors assign much more value to a degree in the discipline than do practicing journalists, according to a new Poynter study.

Some 96 percent of journalism educators believe that a journalism degree is very important or extremely important when it comes to understanding the value of journalism. By contrast, 57 percent of media professionals believe that a journalism degree is key to understanding the value of their field.

Perhaps even more significant, more than 80 percent of educators say a journalism degree is extremely important when it comes to learning news gathering skills, compared to 25 percent of media professionals. One in five media professionals finds a degree in the discipline is not at all important or only slightly important in learning news gathering.

The results, based on an online survey of 1,800 respondents, are consistent with findings of a similar study Poynter conducted last year. The numbers of educator and journalist respondents were roughly equal, but Poynter did not ask practitioners if they had journalism degrees.

Poynter finds the opinion gap to be “significant" and one that it will seek to address in its professional development offerings for journalism educators, students and professionals, in the coming months and years, said Howard Finberg, director of training partnerships and alliances and creator of the organization’s NewsU. Poynter likely will conduct similar future studies to monitor progress, he said.

Finberg, who authored the study, attributed the discrepancy in part to a kind of digital divide between journalism school curriculums and what’s expected of journalists in the field. Working journalists feel the demand for new multimedia skills that may or may not be part of traditional journalism coursework, he said, leading them to question the value of degrees in the discipline.

That’s consistent with another key finding in the study: both educators and journalists question the rate at which education is keeping up with industry changes (39 percent of instructors said journalism programs were keeping up with changes just a little or not at all, as did 48 percent of editors and staffers).

Thinking back to the last person their organization hired, only 26 percent of media professionals say the person had “most” or “all” of the skills necessary to be successful, according to the study.

"We have to blow up our current curriculum to understand how this generation of students learns -- and how they can best learn their talents to become the communications leaders of today -- and tomorrow," wrote Neil Foote, a principal lecturer at the Mayborn School of Journalism at the University of North Texas, in an open-ended comment section of the survey.

Finberg said the study offered two "big takeaways. On the academic side, I think journalism educators should start experimenting and innovating and using digital tools and more innovative teaching methods.”

As for students and professionals, Finberg said, "[They] need to have a stake in their education, and they need to raise their voices as to what they want and need to see in [journalism programs].”

Journalism professors said the opinion gap is nothing new to journalism. And while there’s an ongoing need to shape programs to better-prepare students for a rapidly evolving field, the discipline as a whole isn’t doing a good enough job – perhaps ironically – publicizing the changes it’s already made.

“That is a trend we see that goes back to the creation of the first journalism school in 1908,” said Jennifer Greer, professor of journalism at the University of Alabama and chair of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication’s Committee on Teaching. “There’s a division between the practitioners who think we’re in the ivory tower and people in education not getting the word out about what we’re doing. …Sometimes we get so busy with the day-to-day business of educating future journalists that we don’t tell the story as well as we should, but there are a lot of innovations and collaborations happening.”

At the University of Alabama, for example, she said, an award-winning community journalism initiative with a digital emphasis affords aspiring journalists the time and resources that traditional news organizations no longer provide.

Maryanne Reed, dean of West Virginia University’s Perley Isaac Reed School of Journalism, said that program is undergoing a kind of “rebranding” to reflect the innovative turns it has taken in recent years, including an emerging emphasis on entrepreneurial journalism. All students are required to learn multi-media skills, such as video and audio editing, regardless of where they hope to land jobs, she said. Faculty, too, are encouraged to participate in multimedia professional development offerings.

“Journalism education hasn’t done a good job of sharing what we’re doing,” Reed said. “It behooves us to be more public about the ways we’re evolving and responding.”

But given that modern journalism is a kind of moving target, experts said, programs can’t afford to lose sight of the fundamentals: good storytelling and strong writing and problem-solving skills.

“It is in no way possible for journalism schools to keep up with all the industry changes because journalism itself isn’t keeping with the technological changes,” said Sonny Albarado, president of the Society of Professional Journalists and projects editor at the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. “It’s important to be exposed to whatever the dominant or latest technology is, but that varies from place to place.”

Albarado said he prefers to hire reporters with journalism degrees, due to their training, but he wouldn't exclude applicants with English degrees, for example.

Ultimately, he said, “I just want somebody who can write and think critically – and spell.”