You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The narrative that today’s college graduates aren’t prepared for work doesn’t appear to be going away, no matter how much college officials (not to mention students) might like that. But one thing does seem to be changing: the willingness of higher education to address the issue.

The latest to shine a light on the problem is Bentley University, which released a survey today highlighting graduates’ struggles in the work place. While it reveals significant conflict between students’ self-perceptions and the extent to which employers believe they’re prepared for work, as well as some disagreement over who should take responsibility for students’ lack of preparedness, Bentley President Gloria Cordes Larson believes there’s much more reason for optimism than pessimism.

Larson says the overwhelming narrative from most surveys – that businesses are finding recent graduates unprepared and even unemployable – does not square with what administrators on her Massachusetts campus hear from recruiters, or with the survey's findings.

Thirty-five percent of business leaders in this survey did say the recent graduates they have hired would get a “C” or lower for preparation, if graded. However, they don’t believe the fault rests entirely with students. Although respondents generally say it’s primarily the students’ responsibility to better prepare themselves for the work place, just over half of business decision-makers and 43 percent of corporate recruiters said the business community itself deserves a “C” or lower on how well they are preparing recent grads for their first jobs. (Many businesses are not training new hires like they used to, leaving colleges and private companies to fill in.)

And nearly half of higher education officials surveyed said the same of their own performance.

"I hear the liberal arts colleges not sounding defensive, the way I think they did a couple of years ago,” Larson said. “What I’m hearing is, ‘We’re all a part of the set of solutions’…. This is an amazing new generation of highly talented kids who are prepared to work, they just work differently than the other generations did. They’re willing to send out those emails at 2 a.m. because that’s how they roll, rather than work 9 to 5.”

Perhaps contrary to popular belief, recent graduates transitioning to work are harshest on themselves: three-fifths said they blame themselves for their level of preparedness. But that doesn’t mean they don't see plenty of responsibility to go around: 42 percent said their colleges deserve some of the blame, while another 13 percent put the onus on businesses to some degree.

But if graduates have come to terms with their own failures, most of their parents have not. While 63 percent of parents of high school and college students give recent grads as a whole a C or lower on their preparedness for the first job, seven in 10 give their own kids an A or B.

The statistically representative national survey of 3,100 high school students, recent college graduates, parents, higher education officials and business leaders is part of Bentley’s PreparedU Project, an initiative to bridge the gap between employers and higher education in an attempt to help students better transition in the work force. The project brings all those stakeholders together in an attempt to find solutions with the problems dogging today's colleges and work force; Bentley itself has a strong focus on business and work preparation.

There is at least one clear and potentially serious disconnect between businesses and young people: what actually constitutes preparedness. While high school and college students are more likely to define preparedness as “being prepared in general,” more business leaders and corporate recruiters say it entails personal traits including “adaptability, having a good attitude, being respectful and maturity.”

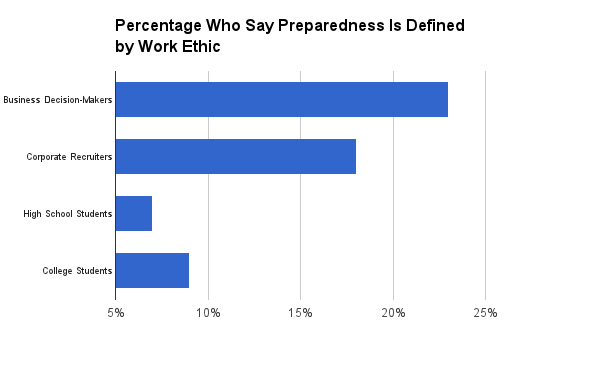

More than 40 percent of businesses and recruiters say preparedness is defined by work ethic, compared to only 16 percent of high school and college students.

While 8 in 10 business leaders say soft skills are most important in an employee, and only 40 percent say hard skills are “very important” to work place success, the majority also say they’d prefer to hire a recent grad with industry-specific skills over a liberal arts graduate who needs training.

While three-quarters of college students “are confident” that simply having a degree is a sign of preparedness to enter the work force, only 62 percent of business decision-makers agree. And almost two-thirds of business leaders said recent grads harm their day-to-day productivity because their new hires are not well-prepared.

However, employers still seem to be having a hard time articulating what exactly they want from employers these days. Much of the criticism about liberal arts graduates’ employability revolves around whether they have the practical preparation to move into the work place – the technical, prescribed, professional hard skills. While these graduates might have strong soft skills – team player traits, communication ability, critical thinking, etc. – some are unsure whether that’s enough anymore.

Turns out businesses might not know either. While 8 in 10 business leaders say soft skills are most important in an employee, and only 40 percent say hard skills are “very important” to work place success, the majority also say they’d prefer to hire a recent grad with industry-specific skills over a liberal arts graduate who needs training.

“These mixed messages suggest that part of the preparedness problem may stem from the business community’s difficulty in clearly expressing its needs,” the report says.

If all parties agree they’re part of the problem – as the survey appears to suggest, at least to some degree – they should also agree that they have a role to play in the solution, the report says. Based on thoughts from all respondents regarding the importance of various skills and opportunities, the report makes some suggestions for improvement.

Students should commit to being “lifelong learners” who follow their scholarly passion, but also take some business and economics courses (and parents should encourage such a mix). Colleges should combine academics with hands-on learning, better incorporate technology, and ensure that career advising begins freshman year.

And businesses should work with colleges to improve career services so everyone’s on the same page regarding expectations for new employees, and should help develop professional curriculums.

“There’s definitely a head of steam that’s building with career preparedness,” Larson said. “I think this is happening universally.”