You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The decline in overall college enrollment has slowed this spring, according to new data the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center released today. And some details are emerging about the groups of students who are less likely to attend college in declining sectors.

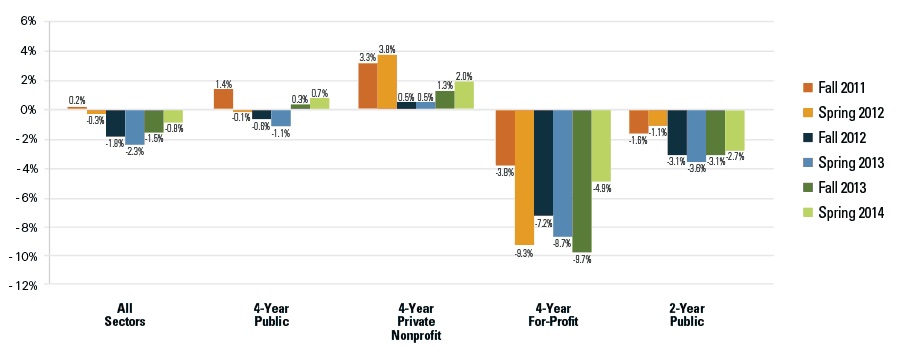

Overall enrollment this spring is down 0.8 percent compared to a year ago. That slide follows two years of previous declines the clearinghouse identified. The loss of students peaked last spring with a 2.3 percent decrease.

The clearinghouse data cover 96 percent of all enrollments in the United States. The nonprofit group conducts student verification and research services for colleges, which turn over their data voluntarily. The clearinghouse publishes national enrollment estimates every six months, breaking out numbers by sectors and states, as well as on students’ age groups, gender and part- or full-time status.

With estimates from the current term, the clearinghouse gives a more timely view of enrollments than the U.S. Department of Education can with its data. However, the clearinghouse does not publicly release figures about individual institutions.

The overall trends in the latest report aren’t surprising. More students attend college during a recession, and an enrollment boom typically tapers off as the economy begins to rebound. Eventually enrollments stabilize and begin to climb again at a steadier rate.

This spring private, nonprofit colleges saw the biggest increase, with a 2 percent gain. At a time when some enrollment-driven private colleges have been struggling and many others fretting, those numbers may come as welcome news.

Public four-year institutions were up 0.7 percent.

Community colleges and for-profits both saw continued declines, but less than in previous reports from the clearinghouse.

The economy is a likely suspect in the 2.7 percent enrollment dip at community colleges, experts said. The new numbers back that theory, in part because adult students accounted for most of the decline at two-year colleges.

College students who are 24 years old or younger are less likely to have been drawn away from their studies and back to the work force. Enrollment for this group was down only slightly (0.5 percent) at community colleges. But for the over-24 age group, enrollment shrank by 6 percent.

That trend was reversed at for-profits. In recent years the institutions in the sector have been hit hard by regulatory scrutiny and bad publicity, as well as by having a harder time selling their relatively high tuition levels to prospective students. Those pressures contributed to an almost 10 percent enrollment decline at four-year degree-offering for-profits last fall (compared to the previous fall) and a 5 percent dip this spring.

Traditional-aged students in particular appear to be steering clear of bachelor’s degree programs at for-profits. This group was down 5.8 percent, compared to a 4.7 percent decline among adult students.

The 'New Normal'

For-profits pioneered large-scale online education. But they have more competition these days, which the clearinghouse report appears to show.

Southern New Hampshire University’s online division is on pace to double its enrollment of just two years ago, with a projection of 36,000 students this year. That probably accounts for much of New Hampshire’s overall enrollment increase of 16 percent this spring, which topped the percentage increase of any other state.

Many of Southern New Hampshire’s online students live outside the state, but the enrollment numbers count toward New Hampshire in the clearinghouse report. That research conundrum is likely to worsen as online education grows.

“We’re going to have to think about what state-level enrollments really mean,” said Jason DeWitt, a research manager at the clearinghouse’s research center.

Spring enrollment figures tend to be lower than fall ones. Student retention is a factor -- as students drop out during the year -- but it’s not the primary reason. Students both enroll and leave college throughout the academic calendar.

“It’s not like everybody starts in the fall,” DeWitt said. “But it’s more common for students to start in the fall.”

The fall enrollment glut accounts for most of the difference between fall and spring numbers, he said.

This year spring enrollments were down 4.7 percent compared to the fall. That decline was 5.4 percent the previous academic year.

While community colleges and for-profits have yet to hit the bottom in their enrollment slides, today’s report at least shows that the hemorrhaging has slowed. Even so, the future remains murky for both sectors.

Community colleges are unlikely to see big enrollment gains anytime soon, said Davis Jenkins, a senior research associate with the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

State budget pressures remain a problem, he said, and the federal government probably won’t earmark much new money to the Pell Grant Program. Those two flat funding streams will make it harder for community colleges to open up slots for more students. And reforms to remedial education -- even if sorely needed -- may also mean less money and enrollments for community colleges.

“This looks like the new normal,” Jenkins said.

He said the best way for the sector to ensure healthy enrollments and budgets is by doing a better job of retaining students. Fully 42 percent of community college students drop out in their first two terms, Jenkins said, citing a previous CCRC study.

“More than ever, community colleges are going to have to face up to their retention issues,” said Jenkins.