You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As the Obama administration weighs public comment on its second proposal to more tightly regulate for-profit colleges, the industry is once again fighting in earnest to fend off the regulations.

But this time the debate over the “gainful employment” rules is playing out across a different landscape.

The for-profit sector has been hit hard by years of slumping enrollments and revenue. Even so, industry advocates are pushing back hard on the proposed regulations with lobbying, grassroots campaigns and an expected legal challenge. But they face a White House that appears unlikely to back down, and has the strong support of a network of consumer advocates and unions.

In the first three months of this year, for-profit education companies spent at least $1.9 million on lobbying expenses, according to an Inside Higher Ed analysis of lobbying disclosures. Apollo Education Group, the Association for Private Sector Colleges and Universities, Bridgepoint Education, and Corinthian Colleges were among the highest-spending entities.

The high-water mark for for-profit industry lobbying was 2011, when it spent more than $10 million advocating against the administration’s first gainful employment rule, which was later tossed out by a court. Since then, lobbying expenditures by the industry have fallen, according to data analyzed by the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets project.

For observers and advocates on both sides who witnessed the previous gainful employment debate play out, the past few months are a bit of déjà vu.

Major national newspapers’ editorial pages are weighing in (pro and con) on the issue. Proponents of tighter regulations are blasting emails to their supporters to press the administration to strengthen what many of them see as a proposal that is far too weak.

And the main trade association for for-profit colleges in Washington, the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities (APSCU), is again stepping up its advocacy efforts.

This Week @ Inside Higher Ed

We'll discuss this story and other

topics on our weekly audio

newscast Friday. Listen to last

week's premiere or sign up

to receive each week's program

via email.

The group has launched a new site -- Higher Education For All -- and is running online advertisements that seize on a disputed statistic that the Education Department has been using to make the case for tough federal oversight of for-profit colleges.

Much of the group’s recent focus has been on speaking to members of Congress about the proposal, according to its president, Steve Gunderson.

In addition to a “lobbying day” last month, the organization has been organizing meetings with Congressional lawmakers in Washington and in their districts.

“We’re working hard to make sure that constituents are part of these meetings,” Gunderson said. “It’s when people from back home talk to their member of Congress that they listen. If it’s a personal relationship, that’s important, too.”

Gunderson said he has attended many of the meetings. “The overwhelming reaction across the ideological spectrum is that ‘you shouldn’t be asked to meet a standard that others in higher ed aren’t asked to meet,' ” he said.

“Most of our conversations are with the Congressional branch,” Gunderson said, noting that they have had few meetings with the White House and Education Department outside the formal regulatory process. The group plans to submit written thoughts on the proposed rule before the public comment period ends on May 26. The administration has said it wants to issue a final rule by November.

At individual for-profit colleges, too, mobilizing students and employees in opposition to the administration’s gainful employment regulations has been part of the organizing strategy.

Education Management Corporation (EDMC), for example, has revived an online campaign that calls on students, parents, instructors and employees to write to Congress to block the regulations.

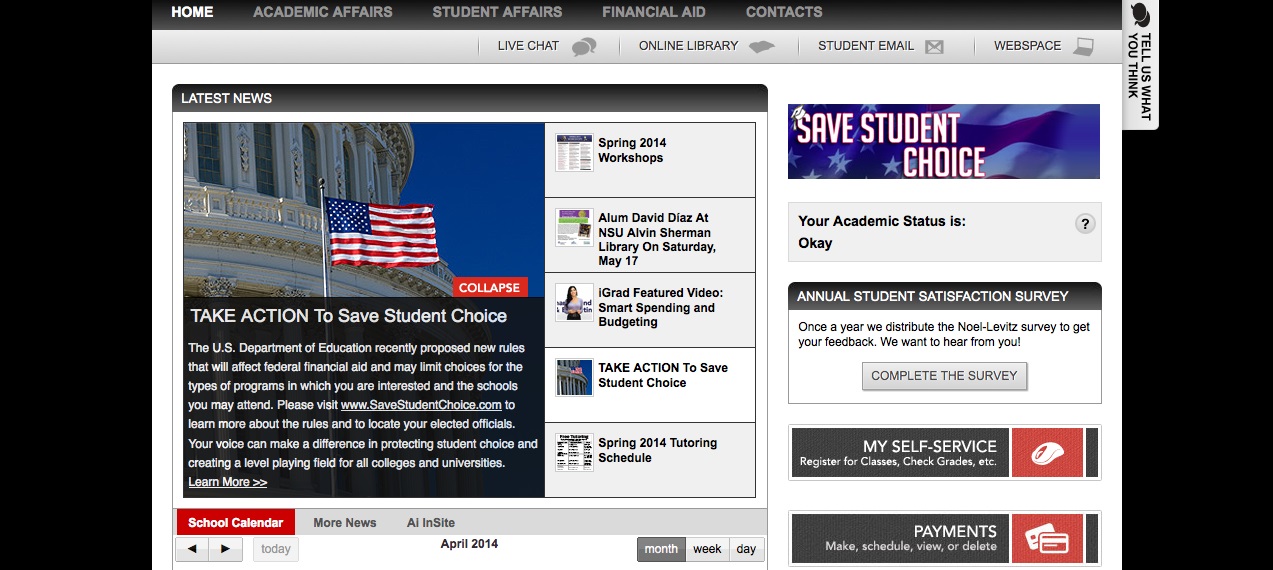

At least one EDMC-owned college is also taking the political message to students directly. On an Art Institute portal where students log on to check their email and see important information about their academic progress, students are greeted by two banners that urge them to “Save Student Choice.”

Thomas McLendon, a 28-year-old student from Miami who attends the college’s Ft. Lauderdale campus, said the banners caught his eye and prompted him to sign the form letter to lawmakers.

“If something like this passes, I could possibly not be able to go to school here anymore,” he said of the gainful employment regulations. “I felt obligated to say something about it,” said McLendon, who posted messages about the Save Student Choice campaign on both his Facebook and Twitter accounts.

McLendon, who is working toward an associate degree in video production, said that he and his peers enrolled with the full knowledge that the Art Institute is a for-profit company.

“We understand that. We knew that. That is what they want to do,” he said. “You can’t stop someone from making money.”

David Halperin, an advocate who has been organizing to push the Education Department to enact stricter rules on for-profit colleges, said he has noticed less of a focus this time from both sides on trying to gain widespread support.

“The public isn’t really listening,” he said. “Neither side is really going to be effective in rallying the public. This remains a policy issue sort of under the radar, so the focus is on the face-to-face lobbying on both sides and on campaign contributions by the industry.”

Gunderson said he didn’t want to speculate on how much APSCU -- whose political action committee donated more than $350,000 in the 2012 election, overwhelmingly to Republican candidates -- would spend on the midterm elections, but noted that “I don’t think you’re going to see any change from what we’ve done in the past.”

Proponents of Strong Rules

For-profit critics say that while they think the administration’s current proposal is too weak, the policy environment has shifted in their favor since the administration first contemplated gainful employment rules.

They point to what they call a mounting body of evidence that predatory practices are widespread throughout the industry. Chief among that evidence was the 2012 report by Senator Tom Harkin, the Iowa Democrat who chairs the Senate education committee.

And some Democrats have sharpened their rhetoric. Just last week Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois sent a letter to high school principals in his state urging them to steer students away from for-profit colleges. (The letter earned a swift retort from Illinois-based DeVry Education Group).

President Obama has also weighed in directly on problems at for-profit colleges. He said during a town-hall meeting at Binghamton University last August that students at some for-profit colleges are "loaded down with enormous debt" while "the for-profit institution is making out like a bandit." His education secretary, Arne Duncan, has recently been aggressive in his criticism of the industry. And no for-profit college got an invite to the White House’s higher education summit in January.

The coalition of groups pushing for tighter regulations has grown slightly since 2010, but remains largely the same, according to Pauline Abernathy, vice president of TICAS, which has been one of the leading voices in that group.

The State of Federal Rule Making on Gainful Employment

|

2011 Draft Rule |

2014 Draft Rule (Current Proposal) |

|

Programs would have been fully eligible for federal aid if they met one of three standards: (1) student loan repayment rate of at least 45 percent; (2) debt burden less than 8 percent of their graduates’ annual income; or (3) debt burden less than 20 percent of graduates’ discretionary income.

Programs that were close to those standards, but did not completely meet them, would fall into a “yellow zone” and would face restrictions but would be eligible for some aid.

|

Programs would pass the metrics if their graduates’ loan debt does not exceed 8 percent of their annual income, or 20 percent of their discretionary income. After a program fails this measure for two out of three consecutive years, it loses aid. There is a “warning zone” for programs whose debt-to-earnings ratios go up to 12 percent (based on annual income) or 30 percent (based on discretionary). Too much time in the warning zone would also make a program ineligible for aid. In addition, each program must have a loan default rate below 30 percent. Programs above that level for three consecutive years would lose aid. |

|

2011 Final Rule |

2014 Final Rule |

|

The final rule eliminated the “yellow zone” and eased some of the thresholds. In order to stay eligible for federal aid, each program would have had to meet one of three benchmarks: (1) student loan repayment rate of at least 35 percent; (2) debt burden less than 12 percent of annual income; or (3) debt burden less than 30 percent of discretionary income. Under the final rule, programs would have had more chances to improve, under a “three strikes” process. Programs would have had to fail the benchmarks in three of four years before losing aid. (The final rule was thrown out in 2012 by a federal judge, who ruled that the department’s repayment rate was too arbitrary.) |

Not yet released.

The public comment period on the draft proposal ends May 27. Education Department officials have said they want to publish a final rule by Nov. 1, so that it can take effect by next July.

|

Carrie Wofford is a former Democratic staffer on the U.S. Senate's Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee who helps lead Veterans Education Success, a recently formed nonprofit group that is seeking stronger protection for students who are veterans of the U.S. military.

Wofford and others have amplified complaints of student veterans who say they were taken advantage of by for-profits. One of her allies has deep pockets. Jerome Kohlberg, a billionaire financier and World War II veteran, has created a fund through his foundations to award $5,000 grants to veterans to help them dig out of debt they received while attending for-profits.

In an opinion piece on The Huffington Post published earlier this year, Kohlberg was scathing in his criticism of the sector.

“These for-profit predators must be seen for what they are -- domestic enemies,” he wrote.

Barmak Nassirian, a longtime critic of for-profit colleges, said a key change that for-profit critics made during the second fight over gainful employment was to spread out across separate meetings with the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to get more face time with officials reviewing the proposed regulations.

Last time, Nassirian recalled, a group of 30 people representing the dozens of groups in the coalition packed into a conference room for a 15-minute chat with White House officials. When they later looked at the public records of all of the meetings, they noted that for-profit colleges and their supporters had scheduled individual sit-downs and had nearly two dozen meetings compared to their one.

“That lack of organization last time around didn’t reflect well on us,” said Nassirian, who serves as the director of federal relations and policy analysis at the American Association of State Colleges and Universities. “I think we’re much better coordinated this time, but there are very few ways of trumping money in politics and the other side has nothing but money.”

Nassirian, who was also a negotiator on the department’s rule making panel that failed to reach consensus on the rules last year, said the debate was “clearly a David and Goliath confrontation,” adding that “you have a bunch of multibillion-dollar companies who see this as an existential threat to their business model.”

But while critics of for-profits are outgunned financially -- DeVry disclosed recently that it had almost $400 million of cash on hand -- they have plenty of clout with Democrats.

One notable supporter of gainful employment is the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), a primary faculty union. Craig Smith, director of AFT’s higher education division, said the gainful employment rule is a significant step forward in protecting students from fraud and abuse in the for-profit sector.

Smith said the union had met with White House officials to urge strengthening of the rules, particularly as they relate to programmatic accreditation and restitution to students in failed programs. But he said for-profits are no slouches in Washington.

“For-profit lobbyists have taken many meetings with OMB, they have shown up at both the Senate and House briefings we hosted on gainful employment, and they continue to make their case through the press,” Smith said in an email. “It is naturally their right to do this, but disappointing to see the level of influence they have and how much they are investing in this fight, considering how little their institutions invest in instruction and academic services.”

Financial/Enrollment Woes

Gainful employment may not be the biggest threat for-profits face. Most of the publicly traded chains have yet to hit the bottom of a three-year free fall in enrollments and revenue.

For example, Career Education Corp. saw its overall revenue dip by 21 percent last year while enrollment fell by 16 percent. Several other major for-profits struggled with double-digit declines in 2013. And last week EDMC announced a net loss of $468 million for the first three months of this year. (See an accompanying article on the recent struggles of Corinthian Colleges.)

The lumps for-profits have taken in the news media and from critical politicians have contributed to the sector’s hard times. So has the recession's lingering effects. Most for-profits are struggling to find a price point that is attractive to students, some of whom are enrolling in upstart online offerings from nonprofits like Liberty University or Southern New Hampshire University. Nonprofit competitors online typically undercut for-profits on tuition.

“Students are just looking at the equation of taking on debt differently” after the recession, said Corey Greendale, an industry expert and vice president of First Analysis, a private equity investment group.

The industry’s focus has also been distracted by an onslaught of federal and state investigations that have cropped up over the past several years, some of which have led to litigation.

ITT Education Services, for instance, is defending itself from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's first ever lawsuit against a for-profit college, which was filed earlier this year. The company last week asked a judge to dismiss the complaint, arguing, among other things, that the consumer bureau lacks the legal and constitutional authority to regulate it.

State attorneys general, led by Kentucky’s Jack Conway, have also taken an aggressive posture with the industry.

Yet several officials with for-profit institutions said they are working hard to make sure the White House and Education Department have heard their arguments on gainful employment. And despite their money woes, for-profits still have the resources to make noise in Washington.

“If you don’t try, you’re giving up,” said Kevin Kinser, chair of the educational administration and policy studies department at the State University of New York at Albany and an expert on for-profits. “And they’re not going to give up.”

However, one observer said private equity groups, which own some for-profits and battled aggressively against the previous gainful employment proposal, were spending less on lobbying this time, compared to in 2011. Some don’t think it’s a worthwhile investment given the administration’s commitment to the rules and the likelihood of a legal challenge.

Mark Brenner is a spokesman for the Apollo Education Group, which owns the University of Phoenix, the largest of the for-profits. He said Apollo has been active during the public comment period.

“We believe the department doesn’t have the right approach to this rule making,” said Brenner.

Despite the tough talk from Duncan, Brenner said he believes the White House wants to properly vet the rules and will take Apollo’s comments seriously. “We want to help them get to the right goal,” he said.

Brenner is less charitable about the coalition of for-profit critics who work outside of government. He said some among the group had used “hysterical and nonsensical” rhetoric in the debate.

These critics are “completely clueless about getting to the right place for students,” said Brenner. “I will put our record up against anyone.”

Legal Threat Looming?

Gunderson reiterated in an interview last week that it was too early to determine whether the industry would ask a judge to block the regulations.

His association has again hired an economic consulting firm to analyze how the proposal would affect the industry. The group is commissioning the work from Charles River Associates, carried out by Northwestern University business professor Jonathan Guryan, and plans to release it later this month.

The report, said Noah Black, an association spokesman, will provide “a detailed economic look at where the department has erred on the math.” It will also show how the proposal would disproportionately affect minority students, Black said.

The original rules were thrown out by a federal judge, who said one of the three metrics the department used had been determined arbitrarily. However, the judge also said the federal government was within its rights in the overall goal of seeking stricter regulation of vocational programs.

Industry analysts and advocates for the sector say a legal challenge is inevitable.

Several experts said privately that for-profits might again sue over the arbitrariness of the process. For example, the addition this time around of “warning zones” for programs that are close to failing the metrics might be part of a lawsuit. The industry could also argue that the rules are discriminatory because of their presumed impact on students from minority groups.

However, both critics and supporters of the industry said it appeared unlikely that the White House will back down on gainful employment. Several pointed to Duncan’s aggressive soundbites when the rules were rolled out in March.

Kinser said Duncan and the White House learned an important lesson during their first, failed attempt to make gainful employment stick. The bottom line is that they face an uphill battle when Democrats control the White House and Senate. Of course, that could change if Republicans take charge of both chambers of Congress after this November's elections.

“He recognized the paper tiger,” Kinser said of Duncan's take on for-profits. “They went all-out to stop it, and politically they couldn’t.”