You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

MLA

Individual horror stories about the tenure-track job market in the humanities abound, but data telling the whole tale are scarce. That’s been true since the mid-1990s, when the federal government stopped funding the tracking of humanities Ph.D.s’ careers in the national Survey of Doctorate Recipients. But the Modern Language Association is trying to close the data gap with a new analysis about job placement for English and other modern language Ph.D.s. The picture, called "Where Are They Now?" -- while somewhat bleak -- isn’t as bad as many anecdotes suggest.

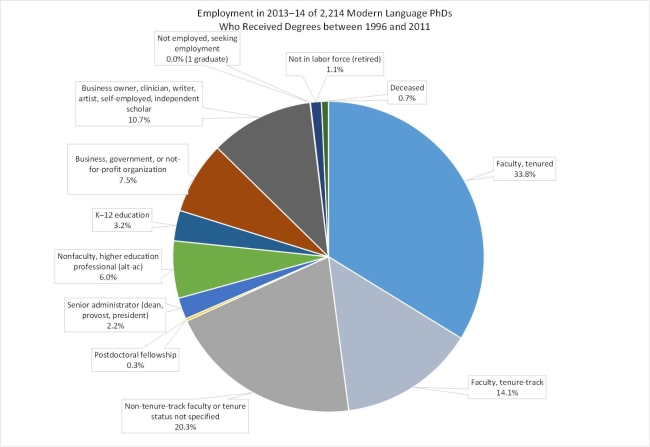

Through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the MLA used publicly available information to determine the employment status in 2013-14 for 2,214 people who earned Ph.D.s from 1996-2011. MLA says the sample isn’t big enough to be representative, but that it’s at least suggestive of where Ph.D.s are working. About half are tenure-line professors, with 33.5 percent of graduates already tenured and 14.1 percent on the tenure track. MLA counted those graduates whose tenure status could not be determined and those definitely working as adjuncts as non-tenure-track. They made up 20.3 percent of graduates -- a significant percentage, but perhaps not as grim as what many humanities observers would predict and what adjunct advocates often say: that they are three-quarters of the faculty nationwide, by some estimates. It's important to note that those numbers aren't necessarily incompatible, particularly given that many long-term adjuncts in languages do not have Ph.D.s and many who want tenure-track jobs can't find them, but the newest figure does challenge the dominant job market narrative.

About 11 percent of the MLA sample is self-employed, and about 8 percent work in business, government or nonprofit work. Some 3 percent work in K-12 education and about 8 percent work in academe as staff or administrators. Less than one-half of 1 percent of the sample are postdoctoral fellows and just one graduate (0 percent of the sample) is unemployed.

Some three-quarters of Ph.D.s are working in higher education: 60.5 percent in the U.S., 4.7 percent in Canada and 11.9 percent overseas. Recent Ph.Ds. (awarded since 2005) are more likely to be working in higher education than the sample overall, while Ph.D.s who’ve had their degrees for longer are more likely to be working in business or government. The MLA report notes it’s unclear if this is something that could repeat itself over time -- meaning that today’s new Ph.D.s working in academe will shift to business and government over time. But it suggests that it’s not impossible to get a job in higher education soon after graduate school.

Some 61 percent of Ph.D.s working in academe are working in public institutions and 37.8 are working at private nonprofits. Fewer than 1 percent work at private, for-profit colleges. Some 44.6 percent work at research universities, while 28.8 percent work at master’s degree-granting institutions. Fourteen percent work at four-year institutions and 9.4 percent work at two-year institutions.

The analysis also shows that Ph.D.s in academe are more likely to be tenured at four-year and master’s degree-granting institutions than they are at research universities. Only 14 percent work in four-year colleges, but 78.4 percent of those faculty members hold tenure-track jobs, and the numbers are similar at master’s degree-granting institutions. At research universities, however, just 61.4 percent of Ph.D.s are tenured.

“Findings from this MLA project suggest the strong orientation toward careers in higher education of people who hold a doctorate in modern languages, literatures and related fields; 77 percent of the Ph.D.s in our sample whose employment we were able to discover hold positions in a postsecondary institution,” the MLA study reads. “Despite the study’s limitations, the findings do tell us that, overwhelmingly, language and literature Ph.D.s find professional employment, often beyond teaching as a tenured or tenure-track faculty member.”

It continues: “The forms of professional success Ph.D.s find are varied. Doctoral programs and their students need to be able to embrace success in the full variety of occupations where graduates in fact find it.”

Rosemary Feal, executive director of the MLA, said that while roughly half (48 percent) of Ph.D.s being on the tenure track wasn’t cause for celebration, it did challenge some of the “myths” about the impossibility of finding a tenure-track job in the humanities.

“In the popular imagination, you might think it was much greater than 20 percent” of Ph.D.s teaching off the tenure track, she said, attributing the discrepancies between perception and reality as reflected by the limited study to the data gap the MLA is trying to close.

Feal also attributed some of the myth’s persistence to the 25 percent of Ph.D.s in nonteaching positions who are largely absent from national conversations about the humanities job market. “We don’t hear from them enough,” she said, noting that MLA is beginning another Mellon-funded project to find out more about their careers and whether or not they’re satisfied. Presuming some of them are, she said, humanities advocates have to keep pushing for more tenure-track faculty lines while better preparing graduate students for a variety of financially stable, intellectually fulfilling careers.

The American Historical Association completed a similar project to MLA's "Where Are They Now?" last year, which produced relatively similar proportions of Ph.D.s working on and off the tenure track and outside academe. James Grossman, director of the AHA, was slightly more pessimistic about the result, saying that 50 percent tenure-track placement rates might mean that “almost half of Ph.D.s who were expecting to find jobs” in academe didn’t.

For that reason, Grossman said, “the biggest takeaway of the report is that we have to enhance graduate education in ways that anticipate broad career horizons and opportunities for students.” And that’s not necessarily a bad thing, he added, “because society will benefit from humanities Ph.D.s doing things other than being professors.”

Robert Townsend, director of the Washington office of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, completed the AHA’s study last year when he was still an official of the association. Townsend said his data were easier to come by, as it was already centralized, and praised the MLA’s hand-gathered approach and overall methodology. (MLA created its sample by tracking down authors listed in Dissertation Abstracts International records in the MLA International Bibliography.) He said both studies show how important it is for graduate programs to prepare students for a variety of careers. Asked if graduate programs were any closer to heeding that advice, which has been part of the graduate education reform debate for years, Townsend said he believed departments were much more “attuned” to it now than they have been in the past.

Townsend said the MLA study would help further reform while clearing up “the troubling disconnect between the conversations and the numbers” about tenure-track employment.