You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

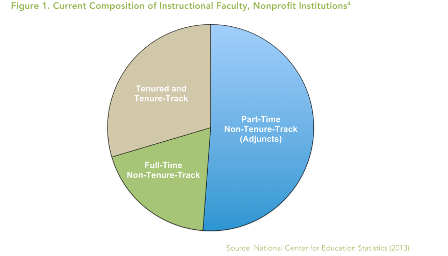

A common refrain from adjunct professors who get relatively low pay and little institutional support is that their working conditions are students’ learning conditions. But many colleges and universities continue to ignore that message and rely on part-time faculty to deliver the majority of instruction. A new paper is calling out those institutions for their lack of attention to faculty career designs and is demanding meaningful, collaborative discussions to address what it calls an existential threat to American higher education.

“[T]here is cause for concern that, with a continued decrease in tenured and tenure-track faculty -- a trend that has progressed consistently over many years -- it will soon be the case that our institutions are no longer able to satisfy their complex missions, which extend well beyond teaching alone to encompass the demands of policy makers and the public,” reads the report from the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success at the University of Southern California, which studies and consults with faculty and administrative groups on non-tenure-track-faculty issues. “Indeed, the core of our educational missions and the status of the academic profession may very well be at risk if we do not make changes.”

Beyond suggesting that adjunct employment not only disadvantages adjuncts and the students they teach, due to the instructors’ lack of institutional support, the paper asserts that the trend hurts tenure-line faculty members, too -- and institutions over all. The “bifurcated” system of non-tenure-track versus tenure-track employment, the paper says, overburdens a shrinking number of tenure-line professors with the nonteaching tasks that keep an institution running: doing research, taking on leadership roles and performing other kinds of service.

“Today, a majority of the faculty has been stripped of the status, privileges and also the concomitant responsibilities that have helped make our institutions of higher learning great -- for many years, institutions that have been the envy of the world,” the paper says. “Given their declining numbers and growing responsibilities, it is becoming difficult for those who remain in tenured and tenure-track positions to continue to uphold obligations for serving the public good that have long been associated with the academic profession. Therefore, the entire professoriate is compromised by today’s situation, not just adjunct faculty members.”

The paper, called “Adapting by Design,” calls for collective and possibly difficult discussions about how to intentionally rethink the faculty role at both the institutional and national levels. It doesn’t prescribe a one-size-fits-all model, and acknowledges that some institutions may need to tweak their faculty system while others will have to overhaul theirs. But it does advise institutions to reject the “neoliberal” policies that may have informed their treatment of the faculty role, and to adopt an ideology “rooted in service to the public good.”

Adrianna Kezar, professor of higher education and codirector of the Delphi Project, said the report stresses that "we need a new vision for the profession. Students, institutions and faculty themselves will benefit when we develop a model of a faculty for the future that takes into account student success, institutional objectives, external needs and professional support and advancement for faculty. Being a lifetime adjunct is not a profession, nor is a full-time non-tenure track with annual contracts but no chance of promotion."

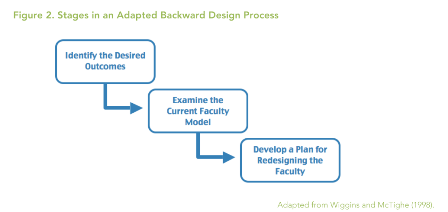

The report advocates a backward design approach to reform, in which colleges and universities imagine how they want their faculties to be structured and supported and then examine current structures and practices. Finally, they plan a way forward. The paper says that planning should be based on four main considerations: the core elements of “professionalism” in all faculty roles; institutional needs and mission; input from a variety of “stakeholders,” including faculty, administrators, students and possibly regional accreditors; and the greater higher education “landscape” and context.

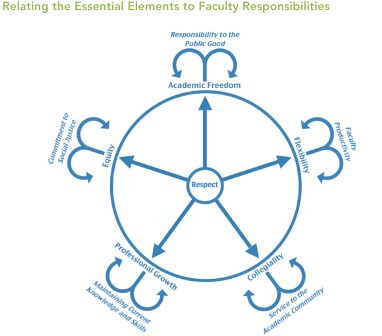

At the “core” of those considerations should be five principles regarding all faculty: equity among academic appointments in terms of pay, evaluation and opportunities; “vigorously promoting” academic freedom; ensuring “flexibility” in appointments, to help professors maintain work-life balance; fostering professional growth through professional development; and promoting “collegiality or a greater sense of community in academic work.”

The backward design approach, borrowed from curriculum design, is relatively simple but “attractive,” said Daniel Maxey, research assistant and codirector of the Delphi Project, and coauthor of the report.

“This is an intentional process that can help campus leaders to think about their desired outcome, based on their institutional missions and goals and values,” said Maxey, acknowledging that different campus factions will have different “priorities” in such discussions. Ultimately, though, he said, the status quo isn’t working for anyone.

“We don’t know what the tipping point is, or when it will come, but there are really serious questions that are raised by current circumstances, and we’d be foolhardy to ignore the implications of what path we’re on right now,” he said. “Change may be difficult to achieve, but we really have got to start to have these conversations.... Right now we have the choice to do that. Later on, as conditions continue to deteriorate, we’ll have to respond to this problem.”

Kezar and Maxey suggest various questions institutions might ask as they tackle the issue. Some examples: What are the guiding values and priorities of the campus community? How are the faculty models that are in place helping to satisfy the institutional mission and achieve other desired goals and outcomes? In which ways are they interfering? And what areas can be identified for improving upon the current model, particularly with regard to the alignment of the faculty models to the attainment of the institutional mission and goals or objectives? Or the public good?

Maxey said that how to approach the issue of tenure in such discussions is a particularly “sticky” question, and that those institutions that have forgone tenure for other arrangements such as rolling or longer-term contracts usually have been able to do so with strong commitments to academic freedom; both he and the report note that when academic freedom only applies to the minority of professors with tenure, the institution suffers.

The report doesn’t advocate for or against tenure, which it says has served the public good over time. But it says that a “desire to maintain the tenure system at any cost cannot be an excuse to avoid addressing the many problems inherent in our current approach.”

In addition to criticizing the adjunct faculty model, the paper offers a critique of the tenure-track model, as well. It says that a “disproportionate emphasis on conducting research and publishing have essentially downplayed the importance of teaching -- the core mission of most institutions.” It also says that tenure costs institutions some flexibility to hire in new fields or account for market fluctuations.

“Adapting by Design” also provides examples of institutions that have reformed the faculty role over time. Maxey said colleges and universities traditionally have argued that fixing their systems to better support faculty of all types would be too costly, and that the examples show it can be done.

The paper talks generally about a small but growing trend toward colleges offering full-time, non-tenure-track appointments of three to five years, and endorses the practice as a way to provide instructors some job security. The paper specifically mentions Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis, which several years ago combined lots of part-time positions to create full-time appointments with better salaries, benefits and opportunities for promotion. Among nontraditional colleges, the paper notes that Southern New Hampshire University’s College of Online and Continuing Education -- which serves tens of thousands of students and has relied largely on adjuncts -- recently announced it will hire 45 new, full-time, non-tenure-track professors with protections for academic freedom.

Maxey and Kezar also say that medical schools seem to be far more open to innovation than other programs and could provide valuable models. The authors say that medical schools, faced with volatility in the health care market and other challenges, have made a number of “major shifts” in the last 10 years, including “moving away from a hierarchy of senior status, addressing inequitable working conditions and creating more differentiation among employee tracks and roles to better fit the needs of medical education and alleviate internal tensions among roles.” Medical faculty positions typically work along three tracks afforded equal status -- research, education and clinical -- and how much time will be spent on the primary track and the remaining two is usually specified in a professor’s contract.

The report also notes “creativity contracts,” as described by Ernest Boyer’s classic Scholarship Reconsidered, in which a professor may focus on one professional area -- say, research or teaching -- more than his or her other duties for a given period of time.

In addition to campus-level discussions, Maxey said the report also stresses the need for national-level discussions between various faculty, administrative and other higher education-related associations. In that sense, he said, the report is a departure from the four-year-old Delphi Project’s previous work documenting the adjunct employment trend and recommending best practices for institutions to support adjuncts.

“This report represents a little bit of a shift in focus for the Delphi Project,” Maxey said. “Ultimately, we needed to turn to the future of the faculty in American higher education, and those discussions need to include all stakeholders and constituencies across the academy.”

Maxey and Kezar recommend a list to questions to be taken up by various groups at such a meeting. Stakeholders in graduate education, for example, might ask if all faculty at all institution types really need a Ph.D. Disciplinary societies could ask similar questions and continue to advocate for part-time faculty members. Regional and specialized accreditors could examine and revise standards related to the faculty, while state policy makers can gather better data about adjunct employment and ask college and university leaders how professors can better meet state goals and the public good.

Trustees and other higher education groups also can engage each other and institutional leaders about the future of the faculty model and higher education, the report says, and faculty members can discuss the implications of new faculty models on tenure and academic freedom.

“Finally,” Kezar and Maxey add, “the faculty -- the whole of the faculty -- has a responsibility, at both institutional and sector-wide levels, to engage their colleagues in discussion about the future and to work collaboratively with other stakeholders to reconceive their roles and redefine what it means to be an academic professional in the 21st century, restoring respect for the profession by leading the effort to reform.”

Kezar said that while she didn't think there had been any "across the board" interest level changes in any of these groups, she noted growing attention among some trustees and policy makers and more deans, department chairs and provosts, and tenure-line faculty members. "These [groups] seemed to largely ignore this issues but seem much more interested now in seeking new ideas and solutions than in the past."

"Unionization and media attention have largely driven the attention to the issue," she added via e-mail. "I wish I could say it was the emerging research on the issue and in some cases the negative impacts on retention and graduation that have driven change, but it is mostly external pressures, not internal motivation. We hope this report starts to drive more internal motivations and solutions."

Maria Maisto, president and executive director of New Faculty Majority, a national adjunct advocacy group, said she was familiar with many of the arguments in the report, but most appreciated the Delphi Project’s louder call for a nationwide discussion about the future of the faculty. She said that’s already begun, noting recent Congressional interest in the topic, and said that faculty members -- as called for in the report -- must continue to drive the discussion.

“Higher education has tackled lots of difficult issues in the past, so there’s no reason we can’t do this,” Maisto said. “It’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of honest reflection -- a lot of honest, uncomfortable reflection -- but if we can’t do this in higher education, then what are we here for?”

Henry Reichman, professor emeritus of history at California State University at East Bay and chair, Committee A on Academic Freedom and Tenure at the American Association of University Professors -- which is singled out in the report as one of the groups that can help drive change -- said that tenure can’t be underestimated in any such discussions.

“Tenure has proven to be the best protection for academic freedom, and not only for those who have earned it,” he said via e-mail. “A strong tenured faculty often provides the best defense for the academic freedom of probationary and non-tenure-track colleagues. It has been argued that long-term renewable appointments (say, five or seven years) with due process protections midterm equivalent to those afforded the tenured, will be adequate. But these are not, because there is no protection for a faculty member who becomes controversial when the term of appointment ends.”