You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The best-laid plans often go awry. And in the case of Florida’s performance-based funding model, even the most formula-based system can turn, at times, into something less than an objective process.

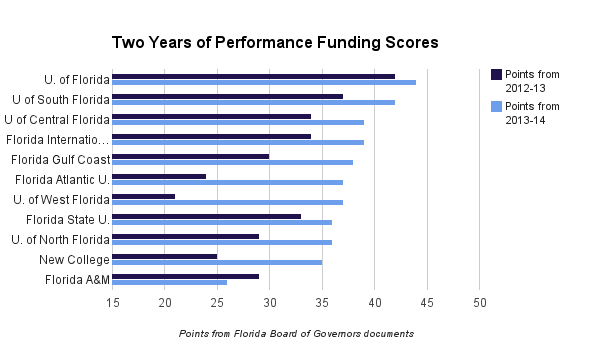

In the two years since the 10-metric system took effect, there have been scoring ties that affect which universities finish in the top and bottom groups. More importantly, those top and bottom classifications influence how much -- if any -- of millions of performance-based dollars universities can claim. So far, the institutions that have lost out on award money are small regional universities, the state's only liberal arts college and the state's only public historically black institution.

At the State University System Board of Governors meeting in March, officials originally announced that Florida A&M University, New College of Florida and the University of North Florida had the three lowest scores, with N.C.F. and U.N.F. both scoring 35 points.

A week later, the board announced that it had made a mistake in calculations and that Florida International University and the University of North Florida each would have one point added to their score.

That adjustment boosted F.I.U. into a tie for the third spot from the top with the University of Central Florida -- for the second year in a row. Extra money for the top three actually will be split among four.

The scoring adjustment also caused a tie between U.N.F. and Florida State University for the third score from the bottom. The rules of the system say that universities with the lowest three scores will not be eligible for bonus money.

But instead of dropping F.S.U. into the bottom tier of universities, the Board of Governors decided the tie would pull U.N.F. out of that group. That means nine universities, instead of eight, will be splitting the bonus money, the amount of which is still subject to approval by the Legislature.

The board didn’t have a tiebreaker policy and didn’t want to create one on the fly. So it decided to consider a tie to the benefit of the universities, not the detriment, said Chancellor Marshall Criser III.

The system is "not intended to punish universities,” Criser said. “It’s to incentivize focusing on the critical metrics we’ve identified in the plan.”

Since the passage of a 2013 law, Florida State and the University of Florida have been considered "preeminent state universities" under a program that's separate from performance-based funding. The designation has allowed the universities to get extra money from the state to improve their national rankings. Criser denied that Florida State's reputation -- or that of any other university -- influenced the board's decision to allow both F.S.U. and U.N.F. to qualify for performance funds.

People tend to look at the performance funding scores as a ranking order, Criser said. But that ignores the data behind each number, he said. The system awards points for excellence or improvement because each university is in a different spot and has a unique mission, he said.

Florida’s system gives financial rewards for scoring well on factors such as postgraduation employment, the average cost of a degree and retention rates.

Yet the system also can punish institutions that perform poorly. The three universities with the lowest scores aren’t eligible for any of the new allocations, and any university that doesn’t score at least 26 out of 50 points risks losing a portion of its base allocation.

Advocate or critic of the system, all agree on one thing: performance-based funding certainly has the attention of the universities, which are adopting strategies to try to be successful according to the standards laid out in the system.

Last year, there was $200 million tied to performance-based funding, including $100 million in new money. This year -- which will affect the universities’ budgets for 2015-16 -- the Board of Governors has asked for $300 million for the program, $200 million that will be reallocated from base funding and $100 million in new money. That's just a slice, about 3 percent, of the universities' total funding. Yet the goal is to continue to grow the size of performance funding.

Left Behind?

New College of Florida was the only institution to score in the bottom three in both years. The small liberal arts college raised concerns about the metrics in the first year under the model. Because of its small size, just a handful of graduates can sway the postcollege outcomes for New College. And last year, the college missed out on points for graduates who left the state for work or graduate school, although because of New College's small size, the State University System used information from its alumni office to count some graduates who were overseas, spokeswoman Brittany Davis said.

Since then, the system has gotten better at capturing where students are one year after graduation, including those students who leave the country or the state, Davis said. The data are now based on about 85 percent of graduates.

Focusing on data collection was one of the improvements officials chose to make after reviewing the system with the universities last summer, Criser said. That same type of review -- and opportunity for tweaks -- will take place again this year.

Improved data on graduates contributed to a boost in New College’s score, which is up 10 points from last year. With more graduates being counted, the median wage of full-time workers from New College jumped 24 percent, for example.

But the college also falls behind due to its cost per degree. With just 834 students, New College has a fraction of the students of the other institutions, but many of the same overhead and administrative costs. The average cost per degree to New College is $76,720, at least $35,000 more than any other institution.

New College certainly faces a handicap under the current system, spokesman Dave Gulliver said. Still, with just three points separating seven of the institutions, the gap between qualifying for performance funds and not qualifying is slim.

Florida A&M University, a historically black college in Tallahassee that serves a lot of low-income and first-generation students, also struggles under some of the measurements.

Much of the university’s population comes from communities with underfunded, underserved public schools. That means FAMU has to provide remedial classes and tutoring that count against it in a category that penalizes colleges for the extra courses it takes to earn a degree, President Elmira Mangum said.

Last year, FAMU’s 29 points placed it in a tie for the seventh spot, meaning it was eligible for some of the new money allocated under the model. In all, FAMU received $10.8 million that was earmarked for performance-based funding for 2014-15, including $5.5 million of new money.

This year, though, FAMU’s score dropped three points, and it placed dead last -- nine points behind New College. The university is just above the cutoff necessary to keep its base dollars out of risk.

FAMU didn’t earn a single point in the average cost per degree ($40,080) or six-year graduation rate (39 percent) categories and earned just one point for retention.

As expected, the university scores highly in the access category, which measures the rate of Pell Grant recipients.

But so does every other institution, even though FAMU outperforms them in this regard.

All but one earned all five points available for the category. At 62 percent, FAMU has about double the percentage of Pell Grant recipients as Florida State University, the University of Florida and the University of North Florida. Yet all three pass the 30 percent benchmark for five points. No further points are awarded for exceeding 30 percent.

Mangum, who took the helm at FAMU last summer, said she would have liked to see the university earn more points for its mission of teaching underserved students. She has to live with the system she has, though.

“There are parts of the formula that we believe may be a disadvantage to us, but we’re invested in it now, and want to provide the opportunities for students so they can be successful,” she said.

She’s not concerned with FAMU’s score as it relates to other institutions and is focusing instead on earning points for improving FAMU’s outcomes, she said.

When students arrive on campus, the university is encouraging them to pursue fields where the students have strengths, rather than choosing majors based on popularity or the appeal of a high-earning job. The university also is focusing on experiential learning, “intrusive advising,” in which students are assigned mentors on the faculty, and raising money to support financial aid for summer courses. All are designed to speed up the time to graduation.

Mangum doesn’t deny that she’s worried about funding -- she always is, she said.

“I do think the students we serve are fully capable of meeting the criteria that the board has set,” she said. “It’s a matter of us organizing ourselves with these metrics in mind.”

Early Gains

While such organization is still taking place on some campuses, lawmakers in Florida have praised the system after seeing large one-year jumps in some universities’ performance.

“The headline writes itself: Performance funding works,” Board of Governors Vice Chairman Tom Kuntz said in a press release celebrating the University of West Florida’s 16-point jump.

The university’s progress was possible because of Florida’s split system of awarding points for either excellence or improvement. Hardly any of U.W.F.’s points were for excellence, but gains such as raising its six-year graduation rate by 9 percent (to 51 percent) earned U.W.F. the highest points in that category.

The university hired three new academic advisers and launched a summer program to target at-risk students, according to the release. Officials also reached out to those students getting close to the six-year cutoff to focus on getting them a degree.

As another sign of success, the Board of Governors has pointed out that none of the universities this year fell below the 26-point threshold that puts base funding at risk.

There also have been systemwide improvements in graduation, retention and time to completion. All of those were once considered slow-moving targets that couldn’t show much progress year over year, Criser said.

But David Tandberg, a professor of higher education at Florida State University, thinks it will take more than a year to determine the effect Florida’s model has on the state’s universities.

No matter how well the system does as a whole, three institutions will inevitably be at the bottom without access to the bonus money. That places a big incentive on finding ways to do better than the year before and better than the other universities in the system, Tandberg said.

He is curious to see the long-term effect on the institutions that are near the bottom. There’s going to be an incredible amount of pressure on them, and it will be a challenge if the same few institutions are continually threatened with losing out on money, Tandberg said.

Those institutions need money in order to innovate, and, he said, that’s the question that is left unanswered: whether this system will provide the resources necessary to improve.

Performance-based funding is useful in that it's language legislators understand, Tandberg said. The model lets lawmakers make the argument that colleges are being held accountable.

The universities have held up their end of the bargain -- going along with the system and starting to make changes to improve. Now, he said, lawmakers have to do the same.