You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When political campaigns enlist college and university employees to spread the word to colleagues and students, they may inadvertently be asking their supporters to break institutional policy -- or state law.

Candidates for president in 2016 are preparing for the early primaries and caucuses in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina and Nevada, where voters head to the polls in February. To boost their grassroots organizing efforts, the campaigns are eyeing colleges and universities in those states as potential sources of volunteers.

“Students tend to be the worker bees for campaigns, and a lot of times they can do the work for free,” said Timothy M. Hagle, associate professor of political science at the University of Iowa.

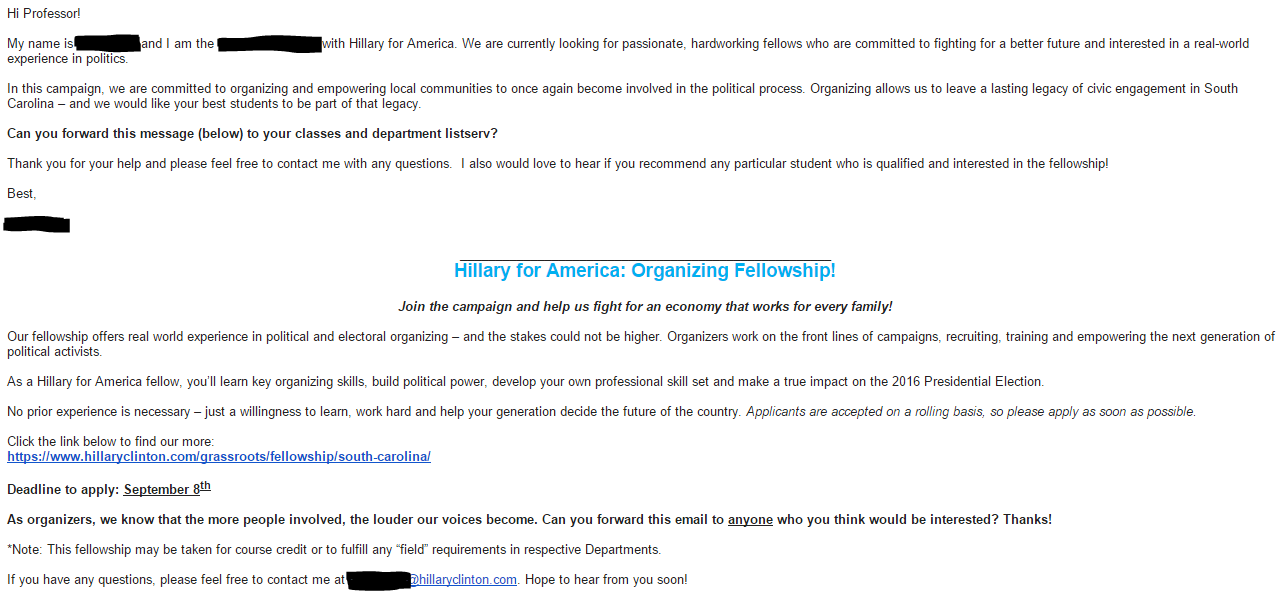

“Organizing allows us to leave a lasting legacy of civic engagement in South Carolina -- and we would like your best students to be part of that legacy,” the email to the faculty member reads. “Can you forward this message … to your classes and department Listserv?”

The message to students contains a second appeal to disseminate it further. “As organizers, we know that the more people involved, the louder our voices become,” it reads. “Can you forward this email to anyone who you think would be interested? Thanks!”

Doing so could land faculty members in trouble. Many states prohibit the use of government resources for political purposes -- in this case, a public university’s network or email system. And while faculty members are in most cases free to share their political beliefs, universities sometimes place limits on expressing support for a candidate in public spaces.

At Clemson, violating those policies could result in disciplinary action, said Robin Denny, director of media relations. Sanctions range from reprimands to suspension or termination, but stricter actions are only taken in response to more egregious offenses, according to official guidelines.

The University of Iowa has similar policies in place. In addition to violating the university’s political expression guidelines, forwarding messages from campaigns may violate the institution’s policies on acceptable use of IT resources and mass emailing, said Thomas J. Snee, a university spokesperson.

The message from the Clinton campaign, however, may be a borderline case, officials at the two universities said. Since it advertises a volunteer opportunity some students may be interested in (as opposed to appealing for donations), forwarding the message may not violate university policy -- as long as the email is sent to students who might be interested because of their affiliation in clubs or organizations, and not to general campus email lists, they said.

Hagle, a go-to political analyst at Iowa, said he regularly receives emails from campaigns and interest groups asking for help. “It seems that sometimes they just sort of send them to everybody that’s in the political science department,” he said.

But instead of passing the messages on his classes in general, Hagle said he will sometimes forward them to relevant student organizations. Hagle is the faculty advisor for the University of Iowa College Republicans, and while members probably would not be interested in volunteering for Clinton’s campaign, that kind of email communication does not violate university policy.

“It’s dealing with political stuff -- which is not allowed -- but it’s really more a matter of supporting that particular group’s activities, which happen to be political,” Hagle said. “Sometimes you just have to think about it a little bit.”

The staffer who sent the email did not respond to questions of whether the campaign is taking the policies into account.

The message did, however, gloss over another issue, adding, “Note: This fellowship may be taken for course credit or to fulfill any ‘field’ requirements in respective departments.”

Hagle pointed out that departments decide if volunteering for a campaign should be worth credit. While the political science department at Iowa may grant credit, he said, that may not be true for departments at other institutions or in other disciplines.

A Clemson professor, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the campaign’s search for unpaid volunteers clashes with Clinton’s higher education plan and its focus on student debt.

“I would argue that the gesture of a campaign saying its internships are worth course credit is symptomatic of broader cynicism about college interns as pool of labor that is free for employers, but actually costs the employees money in the form of tuition,” the faculty member said.