You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Moody’s Investor Service

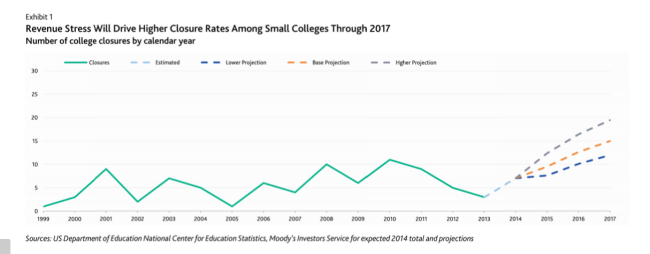

Closure rates of small colleges and universities will triple in the coming years, and mergers will double.

Those are the predictions of a Moody’s Investor Service report released Friday that highlights a persistent inability among small colleges to increase revenue, which could lead as many as 15 institutions a year to shut their doors for good by 2017.

The 10-year average for college closures is five annually. So far this year two colleges have closed, and in 2014 six closed. Moody’s cautions that even as closures are predicted to rise, the number will remain less than 1 percent of some 2,300 existing nonprofit colleges. Meanwhile, the number of mergers is predicted to double, reaching four to six a year, up from the 10-year average of two to three a year.

The main struggle for many small colleges -- which are defined by Moody’s as private colleges with operating revenue below $100 million and public colleges below $200 million -- is declining enrollment.

Small colleges are often tuition dependent, meaning they face financial struggle when enrollment declines or even remains flat. Revenue softness leads to “a reduced ability to invest in academic programs, student life and facilities,” which in turn negatively affects colleges' ability to meet the desires of prospective students, Moody’s notes. And softer demand means that struggling colleges either lose students to other institutions or aren’t able to charge enough tuition to fully cover expenses. A recent report from the National Association of College and University Business Officers found that private colleges offered freshmen an average discount rate of 48 percent last year -- an all-time high.

The result is more and more students enrolling in larger colleges, further contributing to the plight of small institutions.

And a growing number of small colleges are experiencing revenue struggles, Moody’s found. The percentage of small colleges with a sustained three-year growth rate of less than 2 percent increased fivefold, to 50 percent, from 2006 to 2014.

Kent Chabotar, former president of Guilford College and an expert on higher education finance, says many colleges face what he calls “an iron triangle of doom” that makes survival difficult for the underresourced.

“There are fewer students out there. Of those students, fewer are attending colleges and universities. And it’s costing us more to get them in terms of financial aid,” he offered.

Moody’s predicts that struggling public institutions are more likely to merge into a larger system than close, in part because of the political difficulty of closing a publicly funded institution. Meanwhile, private colleges are more susceptible to closure.

Mergers, after all, can be difficult to achieve. For example, the financially struggling Montserrat College of Art attempted to merge with the public Salem State University this summer, but after months of negotiations a merger was deemed too complicated and costly for Salem State.

“It can be hard to make that happen,” said Dennis M. Gephardt, a senior credit analyst at Moody’s. “Even institutional priorities and sensitivities can stand in the way of even semi-obvious mergers. It’s not always straightforward.”

And for that reason, Moody’s expects closures to outpace mergers in the coming years. Yet Chabotar highlights how colleges are historically reluctant to close, and predicts that many struggling institutions will look toward mergers before they consider closing their doors.

“There’s going to be more mergers and alliances than they're projecting. Schools will do anything to survive. The last thing a school wants to do is shut down. Just look at Sweet Briar,” Chabotar said, referring to how Sweet Briar College earlier this year abandoned plans to shut down after a surge of support from alumnae.

It’s this reluctance, combined with the agility of smaller colleges, that leads Richard Ekman, president of the Council of Independent Colleges, to believe that Moody’s predictions are “grossly overstated.”

“There have been predictions of doom and gloom in the past, but it simply hasn’t happened,” he said, recalling how some predicted growing closure rates in the 1990s when tuition discount rates began rising steeply. Yet the number of closures didn’t increase substantially, he said.

“These small, private institutions have this unbelievable ability to be imaginative,” he continued. “Their ability to be proactive is much better than [that of] larger, more cumbersome institutions.”

Gephardt said Moody’s did factor institutions’ tenacity into its analysis. Without that consideration, he said, the number of predicted closures would have been even higher.