You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Instructure’s incursion into the learning management system market reached a new stage last month as the company filed for its initial public offering. As the company prepares to go public, paperwork filed with the federal government suggests Instructure still spends about 80 cents on sales and marketing for every dollar it brings in.

The company behind the learning management system Canvas has come a long way since its founding in 2008, going from start-up to serious contender. Instructure has raised $79.1 million from private equity and venture capital investors, according to CrunchBase. Its products now cover the corporate, K-12 and international markets. In U.S. higher education, Canvas is the learning management system of choice for nearly one in six colleges and universities, according to some market analyses.

Last month, Instructure provided the clearest look so far at the resources that have gone into that work. The company filed a Form S-1 with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, revealing its thoughts on past performance, the risks it sees on the horizon and -- perhaps most interestingly -- how it spends money.

While Instructure has been preparing to go public for more than a year, filing an S-1 is seen as the first step.

The move is welcome news for those watching the learning management system market. Since Blackboard was acquired by the private equity firm Providence Equity Partners in 2011, the major companies in the learning management system space -- Blackboard, D2L and Instructure -- have been privately held. As a publicly traded company, Instructure will be required to produce regular updates on its finances and other information.

The disclosure requirements are already providing insights, for example by putting a price on Instructure’s efforts to get its name out there.

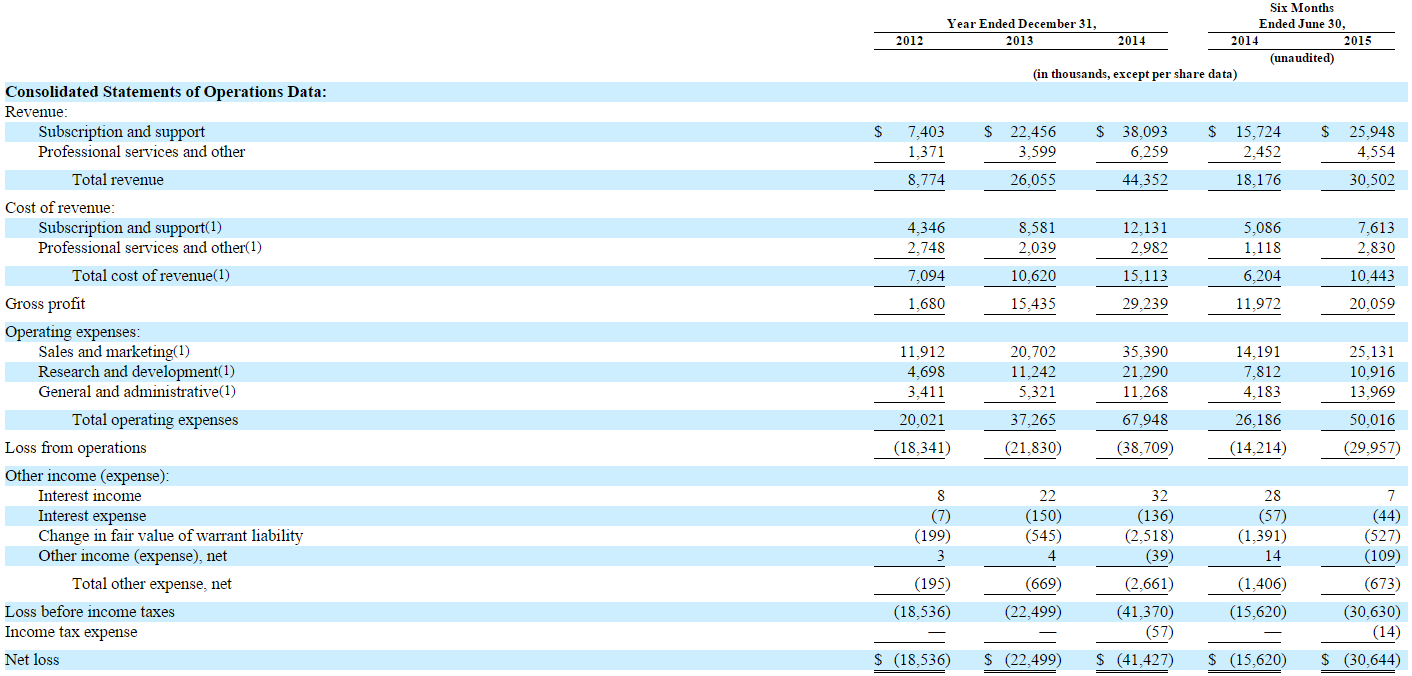

Sales and marketing spending, as a percentage of total revenues, reached 136 percent in 2012 (the S-1 does not include information prior to 2012). Even though Instructure has seen a fivefold increase in revenue since then, spending on sales and marketing has hovered at around 80 percent since 2013.

To put the amount into perspective: during the first half of 2015, Instructure brought in about $30.5 million in revenue. But the company spent $25.1 million on sales and marketing alone during those six months -- more than it spent on research and development ($10.9 million) and administrative costs ($13.9 million) combined. It also cost the company $10.4 million to support its existing clients.

Those numbers are raising eyebrows among Instructure’s competitors. A spokesperson for D2L, which develops the learning management system Brightspace, said in an email that the company spends “approximately 35 to 40 percent” on sales and marketing as a percentage of revenues. That percentage is in line with growth companies that offer best-in-class software as a service, the spokesperson said.

“It’s fair you can say our competition is spending way more on sales and marketing whereas our focus has been more balanced on client satisfaction and innovation,” the spokesperson said.

Although the comparison is not a perfect one, Blackboard’s sales and marketing spending as a percentage of revenues in 1999 reached 503 percent. At the time, however, the company only generated $1.9 million in revenues. Two years later, its revenues outpaced its sales and marketing expenses by almost $20 million. In 2010, the last full year for which Blackboard reported financial data to the SEC, the company’s expenses in that category were only 27 percent as a percentage of revenues.

Blackboard did not respond to a request for comment.

Instructure’s gains in the market can’t be solely attributed to a large marketing budget. The company has previously said it “benefited remarkably” from the fact that it was a new entrant at a time when many colleges looked to migrate from legacy learning management systems facing end-of-life status (meaning they would no longer be supported).

Jeffrey Alderson, a principal analyst at the research and consulting firm Eduventures, said that while Instructure’s spending on sales and marketing may be high, it has at least produced results. (Disclosure: Instructure is an Eduventures client.)

“They needed to become well-known as an alternative to the players,” Alderson said. “They needed to make a point that cloud technology would work for this main flagship platform called the LMS.”

He added, “If they had been spending that much money and only had a trickle of interest, they wouldn’t be going for an IPO. There would be no public interest in what they’re selling. They’ve proven interest.”

Since Canvas is an open-source product, Instructure may also be free to spend more on sales and marketing than on development, Alderson pointed out.

Despite its success breaking into the market, Instructure is not a profitable company. The company reported a net loss of $41.2 million in 2014, nearly double that of 2013. Over the first six months of 2015 -- the most recent data in the filing -- the company lost another $30.6 million.

Instructure is not making promises to potential investors about turning a profit. “We have a history of losses and anticipate that we will continue to incur losses for the foreseeable future and may not achieve or maintain profitability in the future,” the company writes in the S-1.

The disclosure is an example of boilerplate language companies use when they file for an initial public offering. Companies are required in the S-1 to inform investors about the risks associated with buying their stock. Chegg and 2U, two ed-tech companies that have gone public in the last two years, included similar warnings in their filings. Even Blackboard said in its S-1 that it “may never achieve sustained profitability,” but went on to report several profitable years.

Alderson suggested easier access to capital is one of the main reasons why Instructure is going public. Venture capital and private equity firms helped the company get to the point where it is today, he said, but those investors may not be interested in helping Instructure finish up the remaining research and development work.

“Public money is really what’s needed for a long-haul approach, but they have proven to the market that they are viable on a longer term,” Alderson said. “They’re looking for the additional cash to seal the deal.”